BOOK REVIEWS

Practice Models of Rural China’s Ageing in Place: From the Perspective of Multiple Collaborative Governance

Dr Yanxia Zhang is Associate Professor, Department of Social Policy and Development Studies, College of Humanities and Development Studies, China Agricultural University. No. 17 Qinghua Donglu, Haidian District, Beijing 100083, China (yanxiazhang@cau.edu.cn).

Dr Chuanhong Zhang (corresponding author) is Professor, Department of Public Administration and Development, College of Humanities and Development Studies, China Agricultural University. No. 17 Qinghua Donglu, Haidian District, Beijing 100083, China (dianazhang@cau.edu.cn).

Introduction

With its rapidly increasing ageing population, China has entered the stage of a moderate ageing society. According to the seventh national census of China, there were 190 million older adults aged 65 and over in China in 2020, accounting for 13.5% of the total population. More strikingly, the proportion of the elderly population is much higher in rural areas than in urban locations due to the process of industrialisation and urbanisation creating a mass migration of young labourers from rural areas to cities for job opportunities (Yi, Liu, and Xu 2019; Yu, Ma, and Wang 2021). The proportion of rural people aged 65 and over was 17.72% in 2020, 6.61 percentage point higher than that in urban areas. Compared with urban areas, the ageing of the rural population is more prominent in intensity and speed, and the rural-urban inversion of population ageing will continue for a long time.

The migration of rural young adults has not only contributed to the rise in the proportion of elderly people but has also had a serious impact on the traditional family care system in rural China. Rural families are becoming smaller and smaller, and old people and their adult children are separated most of the time, which hinders the realisation of family care functions, cuts off intergenerational emotional bonds, and makes it difficult to provide spiritual support for empty nesters (Li and Chen 2010; Yuan and Zhou 2019; Zheng and Wu 2022). The traditional expectation of “raising children in preparation for one’s old age” has thus been shattered. A big proportion of senior citizens in rural areas also suffers from disability and dementia (Yuan, Liu, and Jin 2020). However, most rural elderly are reluctant to leave the village acquaintance society even after they become too old or sick to take care of themselves, and ageing in the village community is still their primary choice.

The rural ageing population is also facing additional challenges in their rural communities, including limited infrastructure, insufficient transportation networks, and lack of healthcare services (Wilson et al. 2009). Local economic conditions and broad demographic trends are creating disparity in the ability of rural families to care for their elderly kin and in the capacity of communities to support their elderly residents and family carers (Joseph and Philip 1999). The measures to eradicate absolute poverty in China by the end of 2020 have provided basic living conditions for most rural senior citizens to choose ageing in place (AIP)[1] (Nie et al. 2021). However, public facilities and even interior spaces such as toilets, footpaths, level surfaces, and public transport are not provided or well-planned to cater to the security and comfort of older rural dwellers[2] (Bond, Brown, and Wood 2017; Hancock et al. 2019; Ao et al. 2020). Good healthcare services for the elderly are still hard to access in most rural areas in China. Limited family and community support makes rural elderly vulnerable, and caring for them has become a huge burden for families, communities, and the state.

In order to effectively tackle the issues faced by the ageing rural population, the Chinese government has invested in rural healthcare services and encouraged ageing in place since 2013.[3] In 2016, China put forward “home-based, community-supported, and institution-supplemented” (jujia wei jichu, shequ wei yituo, jigou wei buchong 居家為基礎, 社區為依託, 機構為補充) care policies to mobilise resources from all relevant stakeholders for elder care service provision. Most recently, an elder care service system that features “coordinating home and community-based care and institutional care, integrating medical care and health care” (jujia shequ jigou xiangxietiao, yiyang kangyang xiangjiehe 居家社區機構相協調, 醫養康養相結合) has been constructed in both urban and rural areas to support the family, the community, and social institutions in actively playing their roles. With the emphasis on home-based, community-supported care service, diversified elder care services such as village-level “happiness homes” i.e., village-based mutual aid homes for rural seniors (nongcun huzhu xingfu xiaoyuan 農村互助幸福小院), day care centres, mutual assistance among elderly people, and other types of elder care service facilities have started to develop in some pioneering rural areas.

Although the aforementioned policies and measures do not explicitly aim to promote AIP, the concepts contained in them are very much in line with AIP. Even though most rural areas haven’t done much in practice, some pioneering rural areas have explored new models of providing elder care services with AIP characteristics. Many innovative practical models have emerged that are different from traditional family care, and the traditional family care model for the elderly has evolved into a “community + family” model. But the current understanding of AIP in China in academic circles is relatively fragmented, and existing research focuses more on the application of AIP in urban communities, centring on requirements for designing age-friendly buildings and strategies for community-embedded elder care facilities (Zhang 2020). There is still a lack of in-depth theoretical summary and discussion of the emerging AIP practice models in rural China.

Ageing in place is a popular term in current ageing and social policy studies (Chen 2012; Wiles et al. 2012). But the definition of AIP has been evolving in the past two decades, from simply “helping older people to remain in their own homes for as long as possible” to “remaining living in the community, either at home or in a community center, with some level of independence, rather than in residential care” (Davey et al. 2004: 133). Many studies claim that AIP is favoured by the elderly, the family, and policymakers because it not only enables older people to maintain independence, autonomy, and connection to social support, including friends and family, but also avoids costly institutional care (Callahan 1993; Keeling 1999; Lawler 2001; Frank 2002; Means 2007; World Health Organisation 2007). Of course, there are some voices on the challenges and issues related to AIP as a part of the deinstitutionalisation movement, which seems to have abandoned long-term hospitalised ageing individuals with severe and disabling mental disorders (Salime et al. 2022). For many, the sense of home and place attachment has strengthened since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, which enhanced the relevance of improving living arrangements and the sense of belonging for elderly rural dwellers.

Over the past decade, how to create age-friendly neighbourhoods and cities to promote AIP has been studied intensively (Scharlach and Lehning 2013; Buffel, Handler, and Phillipson 2018). Both the physical environment, including housing, transport, and infrastructure, and social dimensions such as social and civic participation, community care, and support from family, friends, and neighbours have been covered in the existing literature, which greatly increases our understanding of how to create a physical and social environment that meets the needs of an ageing population (Gardner 2011; Iecovich 2014; Boyle, Wiles, and Kearns 2015; Lewis and Buffel 2020). However, there has been limited research into the roles and operational mechanisms of different stakeholders in promoting AIP practices.

In China, AIP has been advocated because it allows the elderly to spend their old age in a familiar environment and helps them delay the decline of physical and mental functions and the shrinking of social relations. It is an approach to achieving active and healthy ageing. The connotation of AIP is in line with the current model of China’s community and home-based elder care, goes well with the traditional Chinese family-oriented culture, and meets the actual needs of rural elderly who lack purchasing power for social care services and are reluctant to leave their hometowns or the land.

Theoretical model

The collaborative governance of multiple providers of AIP including the government, social organisations, and market has gradually become a new approach to the supply of social elder care services in China (Jiang 2019). Policy and investment from the government integrated with private resources have been sunk into local communities and coordinated and managed in a unified manner (Wang and Hu 2021). The government takes the initiative to cultivate welfare diversification in China’s market and society, resulting in a “coordination and integration of multiple stakeholders” (duoyuan xietong 多元協同) model: diverse participants are subordinate to the government-led “integration” (Fang and Zhou 2020).

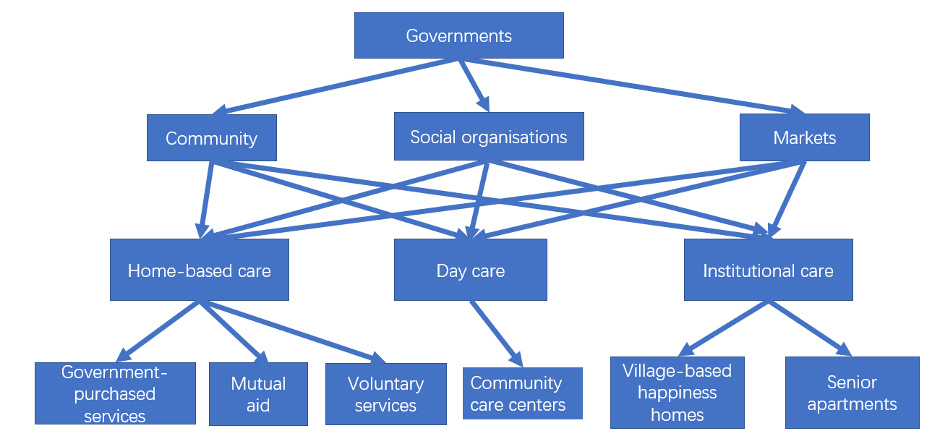

To reveal the complexity of AIP practice in rural China, the theory of multiple collaborative governance is applied. The government, community, and market work together to achieve more than any one sector could achieve alone. According to Ansell and Gash (2008), some conditions are required for collaborative governance to function effectively: support, leadership, and a forum. In the case of China, the leading role of government and increasing collaboration among different stakeholders are the key to effective ageing governance. Based on the theory and practices in China, the following theoretical framework is developed for this study (Figure 1). Under government leadership and support, different stakeholders including the community, social organisations, and markets all participate in care provision in rural China, and three different AIP models that cater to local conditions have been established.

Figure 1. The multiple collaborative governance of AIP in rural China

Credit: authors

In what follows, the article first analyses three main AIP practice models in rural Jiangsu after briefly introducing the methodology. The roles and operational mechanisms of the government, social organisations, market, and local community in promoting AIP practice are explored based on the multiple collaborative governance theory. Finally, how to promote the partnership between different stakeholders for further development of AIP in rural China is discussed to promote the construction of rural age-friendly communities.

Methodology

This article compares and analyses three main AIP practice models with the emphasis on the roles and operational mechanisms of different stakeholders using firsthand data collected from field studies in the countryside of Jiangsu Province, East China. Jiangsu is one of the earliest provinces in China entering an ageing society, and it is also one of the provinces with the highest degree of ageing. The population aged 65 and above accounts for 16.20% of the total population, falling into a moderate ageing society category. The province’s overall level of economic and social development is relatively high in China. Even though there are large internal differences in terms of economic and social development, Jiangsu Province has taken the lead in exploring new AIP practice models in its countryside and is committed to building an effective social care system for rural elderly. Its supply level of social care services for rural elderly is in the leading position in China, comparable to a few other places such as Beijing and Shanghai. Summarising the AIP models in rural Jiangsu and exploring the operational mechanisms could not only fill a gap in existing literature but also have significant implications for the promotion of AIP worldwide.

This article is based on a wealth of firsthand information obtained from field studies on rural elder care services in Jiangsu Province in October 2020 followed by frequent WeChat communication with both the elderly and multiple care service providers. During our field trip, we conducted eight focus group discussions with more than 20 government officials from multilevel government departments including provincial, municipal, county, and township civil affairs departments, human resources and social security departments, health and medical care departments, and financial departments. We also interviewed 21 elderly people from four villages, visited one virtual nursing home (xuni yanglaoyuan 虛擬養老院), i.e., a platform that provides elderly care services through online channel, eight community and home-based elder care service centres (shequ jujia yanglao fuwu zhongxin 社區居家養老服務中心), two village-based mutual aid happiness homes), and one high-end senior apartment complex.

A “structured focused case comparison” (George 2019) was applied to analyse the varieties of conditions under which each distinctive type of causal pattern occurs. In addition to the case comparisons, within-case analysis was also used to further understand the involvement of different stakeholders in the case (Bennett 2010). This study purposely selects two county-level administrative areas from Jiangsu Province as cases for comparison, i.e., Shuyang County in northern Jiangsu, affiliated with Suqian City, which is relatively underdeveloped, and Zhangjiagang City, a county-level city in southern Jiangsu, affiliated with Suzhou City, which is much more developed, ranking among the top ten counties by GDP in China. Among these two cases, three typical AIP practice models composed of several subtypes were analysed to unpack the distinct features and commonalities of each model.

Table 1. Population, GDP, and disposable income of rural residents in Shuyang and Zhangjiagang

| Counties | Population (million) | GDP (billion RMB) | Percentage of aged 60+ | Percentage of rural residents | Per capita disposable income of rural residents (RMB) |

| Shuyang | 1.67 | 116.21 | 18.85 | 40.0 | 21,828 |

| Zhangjiagang | 1.43 | 303.02 | 19.63 | 26.27 | 41,859 |

Sources: The seventh national census of China and the 2021 Statistical Bulletin of National Economic and Social Development.

Practice models of ageing in place in rural China

Based on the differences in care services provided for the rural elderly, we categorise the practice models of AIP in Shuyang and Zhangjiagang into three types: home-based care (shangmen zhulao fuwu 上門助老服務), day care by community care centres, and institutional care by village-based happiness homes and senior apartments. The concept of the three models is in line with the definition of AIP that the elderly person remains in his/her own home and community but the responsibilities and resources of the family, government, and community as well as the private sector are all mobilised.

-

Home-based care

Home-based care can be further divided into two subcategories: government-purchased services, and mutual aid and voluntary services provided by the community and social organisations.

- Government-purchased services

The Jiangsu provincial government stipulates that a monthly government-purchased inclusive care service subsidy of 80 RMB should be provided to each elderly person with special difficulties (including families that receive minimum living allowances, the disabled, and those who lost their only child) for obtaining daily living care, health care, or spiritual comfort if needed.

In Shuyang, the county-level elder care service division, namely the government agency affiliated with its civil affairs office, allocates the tasks of home care to township-level elder care service centres. These centres used to be town-level nursing homes for the elderly, but now the major task of these centres is to dispatch their staff to each village to provide or teach home-based care. They themselves can serve directly in the village or recruit villagers to provide home-based care. Full coverage of home-based care has been established in all villages of Shuyang, with a target of continuously expanding from those incapable of taking care of themselves to all empty nesters, and those aged 80 and above. If the empty nesters and older residents can take care of themselves, the staff only visit them twice a week to check on their daily life and record the visits in the home-call service system. Some empty nesters and older elderly people (over 80 years old) expect more assistance services than this kind of visiting care:

Home-based care is very good, but the services are not enough. The on-site services are mainly to see how we are doing, and we can only be offered basic services. (Mr Zhao, 82-year-old empty nester from Shuyang, interviewed on 22 October 2020 for the first time and followed by a WeChat interview on 12 May 2021)

Zhangjiagang has established a government assistance subsidy system since 2013 covering all elderly who have special difficulties or are over 80, relying on virtual nursing homes to provide home-based care. As of the end of 2021, the city’s virtual nursing homes had a total of 107,500 service recipients, including 46,000 government-funded recipients, and 108 elder care enterprises and social organisations registered to provide home-based care. They offer 42 sub-services in six categories, including advisory services, smart elder care, and daily living care. Since 2016, smart devices such as smart watches and wireless pagers have been distributed to cognitively impaired and disabled empty nesters in Zhangjiagang. Through its virtual nursing home platform, functions such as GPS positioning, emergency calls, and fall alarms have been extended to all elderly in need.

- Mutual aid and voluntary services

With the outflow of the rural labour force, changes in the family structure, and the lack of stable income and security for rural elderly, mutual assistance has become an important way to solve the problem of rural elder care, the “third way” of providing elder care beyond the state and market (Yang 2016). In essence, mutual assistance is a social exchange behaviour developed on the basis of reciprocity. Rural elderly live in the acquaintance society of the countryside and have a strong sense of belonging. They can obtain material and emotional support through mutual assistance between neighbours, among elderly people, and between the young and the old. The cost of mutual assistance is low, but the efficiency of providing elder care services is high, which is in line with the current economic and cultural ecology of rural areas, helps to solve the problem of elder care for left-behind and empty nesters, and supplements traditional family care in rural areas (Liu 2019). Jiangsu Province guides and encourages the development of mutual-aid care in rural areas, providing support for the elderly to get out of their homes and enjoy connections within the village.

“Time bank” (shijian yinhang 時間銀行) is a new system in which younger senior adults and social organisations provide elderly people with daily living care, spiritual comfort, and other services. Younger elderly are encouraged to participate in volunteer services for older ones through the time bank system. The service time recorded can be exchanged for time coins to receive free care services later. Time bank is an innovative approach embodying the philosophy of active ageing. Zhangjiagang launched a pilot time bank program for elder care services in 2020 and has implemented it throughout Zhangjiagang ever since.

Relying on the “Internet + volunteer elderly service” platform, the specific operational mechanism of time bank has been formulated, and the elderly volunteer associations are in charge. People who are 60-69 years old (for females the age span can be extended to 50-69 years old, as many women retire as early as 50) are encouraged to provide volunteer services for those aged 70 and above or in difficulty. This mutual aid service model plays a significant role in promoting AIP in Zhangjiagang. Eleven township-level (district, street) workstations and 253 village (community) service stations have been established to perform these services. Twenty-six social organisations for elder care services have participated, and 2,234 elderly people in difficulties have been covered in the system. Altogether 1,111 volunteers and 76 teams completed 37,289 volunteer services, and a total of 228,000 time coins had been issued by the end of June 2022.

In addition, Zhangjiagang has also carried out quadripartite care action for empty nest seniors in need. Township-level civil affairs officers, community workers, neighbouring relatives, and volunteers sign a quadripartite care agreement with empty nesters and visit them regularly. In the case of physical discomfort, severe cold and fever, extreme weather, etc., the door-to-door visit frequency is increased to ensure the delivery of emergency services and the maintenance of health and living conditions for the elderly in need.

-

Day care provided by community care centres

Communities are the link between the family and society and can also create public spaces and opportunities for seniors to strengthen social interactions and bonds. Both Shuyang and Zhangjiagang have attached importance to the pivotal role of the community in expanding the functions of elder care services. Aiming at improving the quality of home-based care services, Shuyang and Zhangjiagang have explored a new AIP model in the countryside – construction of community and home-based care service centres to meet the various needs of rural elderly, including day care, dining, entertainment, spiritual comfort, and other services. All the centres are operated by professional social organisations in Zhangjiagang with sponsorship from local governments and village committees. Altogether 26 elder care service institutions have participated in this model, which has promoted the rapid development of local social organisations, eventually turning them into a batch of professional service agencies with comprehensive capabilities for providing elder care. Zhangjiagang further upgraded these centres into comprehensive elder care service centres in 2022 to comprehensively improve the level of community care services, covering all kinds of services including day care, short-term care, bathing assistance, meal assistance, time banking, promotion of assistive devices, health management and rehabilitation, sports and entertainment, family empowerment, elderly education, advisory services, and so on.

Village-level elder care service stations are set up in natural villages with a small and relatively scattered population. Venues such as idle school buildings, private houses, and old village offices are often transformed into these service stations. Place selection and the construction and operational funds for these stations mainly rely on governmental subsidies.

In addition to meeting the care needs of destitute elderly, some towns in Shuyang and Zhangjiagang have also established township-level elder care service centres to provide meal assistance services for the general elderly population, relying partly on subsidies from the municipal government to expand the service scope of these centres. Zhangjiagang has carried out a pilot program since 2017 for the standardisation of centres providing meals, in accordance with the idea of “co-contribution by the government, the elderly recipient, and charity” to address the difficulties faced by elderly people dining at home, and to continuously strengthen the function of providing meal services for the elderly within the community.

Mr Qian, a 72-year-old senior who dines at a community meal service site in Jianshe Village, Zhangjiagang, put it this way:

My wife passed away very early and my children often had lunch at their workplaces, so I didn’t want to cook lunch only for myself. Most times I just ate porridge and pickles or the leftovers from earlier meals. Sometimes I didn’t eat lunch at all because I felt bored alone at home. Since the community started to provide meal services, I have been eating lunch here every day, and I feel that the food is very affordable. More importantly, there are many old fellows like myself and we can have nice chats. Having lunch with friends is fun, and my appetite is getting better. I can eat two bowls of rice. (Authors’ interview, 18 October 2020)

-

Institutional care provided by village-based happiness homes and senior apartments

The village-based happiness home is another AIP model for unattended rural elderly. Some villages in Shuyang have combined rural elderly happiness homes with village-level elder care service stations in natural villages to provide rural elderly people with an activity venue similar to a day care centre. They have found a path suitable for economically underdeveloped areas to develop community-based elder care and solve the problem of elder care at low cost in migrant-outflow areas where the elderly and women are predominantly left behind. The happiness homes are operated by villagers for commercial interests, but local governments provide support and regulation.

Ms Sun is a 60-year-old rural left-behind woman in Shuyang. She used to work as a care worker in big cities. After returning to her hometown, she changed her own house into a nursing home for the elderly. The county-level civil affairs department originally planned to shut down this nursing home, but after inspections found that this family-oriented and small-scale nursing home was very popular with the left-behind elderly, officials made an effort to nurture and support its development. With help from the agency, Ms Sun had her house renovated with catering and fire prevention facilities before the agency issued a business license and provided some operational subsidies to her nursing home. Based on this pilot program, the civil affairs bureau of Shuyang issued the “Implementation Plan for Rural Day Care and Happiness Homes in Shuyang County” (Shuyang xian nongcun "rijian zhaoliao xingfu xiaoyuan" shishi fang'an 沭陽縣農村“日間照料幸福小院”實施方案) for standardisation and promotion. More than ten village-based happiness homes have been built in Shuyang. A happiness home is required to be constructed on a scale of less than 300 square meters and no more than ten nursing beds. Day care and institutional care provided by village-based happiness homes go well with the fact that old people hate to be relocated away from their hometowns, and they are also affordable for many old villagers and their families (about 1,000 RMB a month). At the same time, these village-based happiness homes also provide jobs and work opportunities for left-behind women with family obligations.

In some villages with more developed collective economies in southern Jiangsu, such as Yonglian Village in Zhangjiagang, the wealthiest village in Suzhou, seven age-friendly senior apartment complexes have been built specifically for elderly villagers. Women over 50 years old and men over 60 years old can apply for an 80-square-meter apartment. Each couple needs to pay a deposit of only 24,000 RMB. After they pass away, the deposit will be returned to their children, and the house will be reallocated to other seniors in need. A home-based elder care service station has been established on the ground floor of each elderly apartment building to provide them with sports and entertainment, and regular and standardised services, including free and low-paid care services and personalised customised services, and even butler-style high-end services.

The roles and operational mechanisms of the state, market, and social organisations

-

The role of the government

The government directly promotes the development of community and home-based AIP models by providing policies and funding. Jiangsu Province’s plans on rural revitalisation and the development of rural elder care services focus on the improvement of rural capacities for providing elder care, the continuous promotion of establishing care service systems, the construction of elder care service facilities such as community day care centres and village-based happiness homes, and the development of inclusive care services and mutual-aid care systems in rural areas. Through the establishment of county-level care institutions for disabled and semi-disabled elderly, township-level elder care service centres, and the development of rural mutual assistance, home-based elder care, and other services, the elder care service system could cover all rural elderly in need. County-level care institutions, where governmental funds and resources are concentrated, are responsible for incapacitated and destitute elderly with high demand for high-quality elder care services, while township-level care service centres provide basic services to destitute but self-reliant elderly and other old people. Rural mutual assistance and village-based elder care stations are responsible for the elderly in marginal rural areas with limited old-age service resources.

In terms of funding, Jiangsu Province in 2011 began to implement what is known locally as the old-age allowance (zunlaojin 尊老金). The old-age allowance and the elder care subsidy programs were extended to cover all areas including the countryside in 2019. Provincial finance provides the baseline funding and encourages the more economically developed areas to raise allowance and subsidy levels through self-financing.

Zhangjiagang has since 2017 carried out age-friendly home renovations for the elderly, empty nesters, the incapacitated, cognitively impaired, disabled and so on, and has implemented policies according to their needs to reduce the risk of accidental injury and improve their life quality at home. The county-level government has invested more than 1.92 million RMB to renovate 1,114 homes.[4] Since 2021, based on the concept of co-contribution by the government, the family, and the implementing enterprises, the scope of coverage has been further expanded, and 7,000 age-friendly houses are to be renovated by the year 2025.

The construction and operational funds for village-level elder care service stations mainly rely on governmental subsidies. Zhangjiagang’s county-level administration and affiliated townships provide each village-level elder care service station with a one-time subsidy of 40,000 to 50,000 RMB in construction funding, and an annual subsidy of about 60,000 RMB in operating funds, while Shuyang’s county-level administration and affiliated townships provide a one-time subsidy of 30,000 to 50,000 RMB as construction funding and an annual subsidy of 5,000 RMB as operating funds according to their financial capacities.

-

Increased collaboration between the government and other stakeholders

In the absence of other stakeholders, the government actively cultivates and supports various social forces to participate in the establishment of community and home-based care services, and mobilises various social forces including social organisations, markets, charity, and voluntary services to play a role.

The first is to transform and upgrade township nursing homes into township-level elder care service centres, which promotes the development of home-based elder care services supported by the community. After the recent reform of township jurisdictions in Jiangsu Province, the area under one town’s jurisdiction was enlarged due to the merging of two or three towns. In order to provide sufficient rural elder care services, Jiangsu Province implemented the “double upgrade and renovation” project to transform and upgrade a number of public nursing homes located in the town centre or administrative villages with good infrastructure into town-level elder care service centres (xiangzhen quyuxing yanglao fuwu zhongxin 鄉鎮區域性養老服務中心). For example, Zhangjiagang upgraded and transformed a nursing home in Tangqiao Town into a township-level elder care service centre. The government provided 20 million RMB in financial support during the transformation process, of which Suzhou’s prefecture-level financial subsidies accounted for 30%, Zhangjiagang’s county-level subsidies accounted for 25%, and the remaining 45% was financed by Tangqiao Town.

These new township-level elder care service centres are run by nonprofit social organisations and provide both institutional care and home-based services outside the institutions, while the former township nursing homes were public and couldn’t provide other services beyond institutional care. Based on their own geographical locations and service resources, these town-level elder care service centres cooperate with surrounding community and home-based centres to deliver elder care services to towns and villages and thus form a service network, allowing rural elder care services to expand from serving only the destitute elderly to meeting the needs of the general elderly population. By the end of 2020, there were 700 elder care service institutions in Jiangsu Province that basically functioned as town-level elder care service centres providing institutional care to 19,300 rural elderly people. In addition, they also provided home-based services, disability care, spiritual comfort, education and training, and other services as well as visiting the left-behind elderly and providing basic services.

-

Operational mechanisms between different stakeholders

The government manages the home-based care service market by creating a “virtual nursing home” platform. Virtual nursing homes have been promoted as an economical and convenient way of supporting the elderly. Using internet technology, they can meet the phased and personalised care needs of old people at home more conveniently and quickly, and realise the integration of community and home-based care and institutional care to improve efficiency and quality. Virtual nursing homes perform comprehensive and integrated functions in the sense of elder care synthesis, reduce transaction costs, and market optimisation. The elder care service system is mainly home-based and achieves effective management through the application of “Internet +” information technology and virtual nursing homes (Luo and Shi 2016).

Jiangsu Province has continuously improved this smart network system of elder care services. Each county (city, district) has built at least one virtual elder care home, initially forming a “15-minute care service circle,” meaning that old people can get the services they need within 15 minutes. The government has introduced market forces into the elder care industry by purchasing this new type of home-based care service, i.e., virtual nursing homes. A virtual nursing home is like a “nursing home without walls,” where the elderly can choose and enjoy professional home care services without leaving their homes (Liu and Bao 2012). The refined management of home-based care service needs through the Internet has enriched the market, improved quality and efficiency, and explored new ways of providing door-to-door services to the elderly at home and thus solve their home-based care problems. This has encouraged the government to purchase more community and home-based care services and provide more targeted care services for the extremely poor, living-alone elderly, and empty nesters.

Zhangjiagang and Shuyang have taken different paths in the operation of the virtual nursing home platform. Zhangjiagang established four virtual nursing homes in 2007, relying on government procurement and socialised operations to provide home-based care and smart care services for the elderly under its jurisdiction. The virtual nursing home of Zhangjiagang City is managed by the civil affairs bureau with affiliated workstations, and home service stations under the workstations provide overall coordination, supervision, and management. Old people dial the online dedicated line for consultation and to call for services, and professional service companies, various home service stations, and care institutions then provide specific services accordingly. This virtual nursing home costs 1 million RMB in governmental funding every year and has attracted 85 service-providers to be engaged in its socialised operation with more than 800 care workers.

Considering the relatively limited economic and financial resources in Shuyang, the county-level civil affairs bureau introduced a private enterprise to establish an online platform call centre. After old people order care services through the online platform, the newly-transformed town-level elder care service centres dispatch their staff to provide door-to-door services, thus extending care services offered by the former township nursing homes to old people outside the institutions. On the one hand, it helps to increase the income of their former staff, and on the other hand, it provides home-based services to old people and helps them save on travel costs.

Shuyang also supports rural left-behind women in establishing village-based happiness homes as discussed earlier. In addition to providing funds for standardised renovations with catering and fire prevention facilities, i.e., a one-time construction subsidy of 50,000 RMB after the happiness home has operated successfully for over six months, it also provides an annual operation subsidy of 30,000 RMB and incorporates village-based happiness homes into its unified management of elder care institutions. The small governmental investment in village-based happiness homes helps solve the problem of caring for rural left-behind elderly and diversifies the care service providers.

The government is no longer the only and main provider. The integration of multiple stakeholders including the government, village committees, social organisations, old people, and left-behind women helps form a pattern of co-construction and collaborative governance. The mutual assistance of rural elderly thus helps combine institutional care and home-based care and alleviate the care deficit of rural empty nesters and left-behind elderly. Village-based happiness homes provide institutionalised and standardised care services for rural elderly to cope with the increasing challenges of an ageing population (Zhu and Ding 2021).

The government’s promotion of direct corporate sponsorship for elder care projects dispels enterprises’ concerns about the efficient use of their funds and has turned into another operational mechanism. Jinfeng Town in Zhangjiagang has established such a mechanism. Shagang Group, a local enterprise, provides meal sponsorship to elderly people over 60 years old in Lianxing Community (shequ 社區) under Jinfeng’s jurisdiction. Another village in the same town, Jianshe Village, is connected with several local enterprises who pledge to donate to charity care projects for community elder care service centres.

Overall, Shuyang and Zhangjiagang have both taken a multilevel, multichannel, and diversified approach to their rural AIP care provision. The government cooperates with social organisations, markets, villages, and other stakeholders to extend care services to rural communities. A certain synergy among multiple subjects has been formed through integration, coordination, and unified management, and multiparty forces have linked and complemented each other to build an initial partnership. Compared with Shuyang, Zhangjiagang has more advantages in terms of multiple collaborative governance by various stakeholders, especially in encouraging nonpublic capital and mobilising professional social organisations to provide community and home-based care services for rural elderly. There are 26 professional social organisations engaged in elder care services, and more than 1,000 community and home-based elder care service practitioners have deeply and comprehensively participated in rural AIP care provision, with the socialised operation rate of community elder care service facilities reaching 100%. These efforts have effectively promoted the professional development of community and home-based elder care services in Zhangjiagang.

As Mr Li, head of the Zhangjiagang civil affairs department in charge of elder care services, put it:

Zhangjiagang has successfully cultivated a number of local social organisations to provide elder care services. The Yonglian Huimin Service Centre and Yonglian Huilin Social Work Organisation were initiated by the Welfare Foundation of the Yonggang Group in 2014 to provide elder care services for local rural seniors. It has developed into a professional community and home-based elder care institution – Zhangjiagang’s only local institution that can provide comprehensive professional care services for the elderly. Another large elderly day care institution in Zhangjiagang is Huaxia Leling, a social organisation established in Jinfeng Town in 2015. It hired only three care workers at the beginning, but now it has more than 80 full-time social workers, plus more than 200 female care workers who can provide door-to-door home services to the elderly, and its annual turnover reached 10 million in 2019. (Authors’ interview, 20 October 2020)

Conclusion and discussion

As China rapidly enters a moderately-aged society, it is challenging for most rural elderly to rely on their children to take care of them due to the One Child policy and the outflow of young people from rural areas. Besides, the majority of them still prefer to remain in their villages in old age. Ageing in place models are compatible with rural old people’s insufficient purchasing power, traditional Chinese family-oriented culture, and unwillingness to leave the countryside. AIP is an important way to achieve active and healthy ageing in rural China. AIP practice models of “community + family” that differ from traditional family care in rural areas, and rural innovative experiences and cases have emerged increasingly in some pioneering localities. This paper focuses on analysing two typical cases with different economic development statuses and their local experience with substantial pioneering practices in rural AIP. There are three main AIP practice models in both cases, namely, home-based care, day care provided by community care service centres, and institutional care by happiness homes or senior apartments. Nonetheless, there are many differences in terms of service recipients, service content, funding sources, operational methods, and the collaborative governance of multiple providers between these two cases.

In the rural areas of relatively underdeveloped northern Jiangsu as shown in the case of Shuyang, the government mainly provides home-based assistance to the elderly with special difficulties, as well as to elderly empty nesters through upgraded town-level elder care service centres (nonprofit private organisation) and mobilised idle human resources (e.g., left-behind women) in rural areas. Meanwhile, the community and home-based elder care service centres provide day care, meals, and leisure and entertainment services for active elderly people. The care provided is mainly basic services relying on the organic integration of government purchases and market-oriented operation. In the more economically and socially developed rural areas of southern Jiangsu, as shown in the case of Zhangjiagang, the government relies not only on government and community-sponsored elderly service centres, but also on professional elder care enterprises and social organisations that the government has made great efforts to cultivate in recent years. The targets of care provision are not restricted to those inclusive care service recipients funded by the government, and the service content is not limited to basic care services but also includes more specialised and socialised services, and the government provides more powerful policy support and capital investment. Compared with the northern Jiangsu government, it has cultivated more professional social organisations, and has stimulated more market capital, charity, and mutual support forces from civil society.

Despite the aforementioned differences, as shown in this article, the implementation of rural AIP care provision in these two places has applied a multilevel diversified policy through multiple channels. Through governmental investment and coordination, resources from different contributors are sunk into the community and form a synergy between multiple stakeholders, and a partnership linking and complementing multiple forces has been initially established. Various mechanisms, including virtual nursing homes, time banks, and professional social organisations, have been mobilised to facilitate rural AIP practices. These diversified models and their operational mechanisms may provide important experiences and lessons for the development of AIP in rural China and may have some enlightening significance for the exploration of the future of AIP in China and even the world.

However, as a developing country, compared with many developed countries, China has a low starting point for AIP in rural areas, and there are still great deficiencies in the physical environment of home and community, health care services, and intelligent technology. Most innovative AIP practice models discussed in the paper are still limited to those who qualify for national inclusive elder care services. For the general elderly population in rural China, care service provision and resources are still relatively insufficient, and this has a negative impact on their quality of life and self-care capacity. The social care culture of respecting and loving the elderly has not been fully developed at the village level. Mutual assistance and voluntary care play only a complementary role in rural elder services provision and still face many institutional and sustainability problems. The government and other social forces have only established an initial partnership, and there is still a wide gap among different rural areas of China with different levels of development.

In the future, the government should provide more policy support and capital investment to facilitate rural AIP practices. Joint forces from professional social organisations, the market, and communities need to be extensively cultivated and consolidated to form cooperative partnerships of various stakeholders. To further promote rural AIP practices, the physical and social infrastructure of both community and home-based care should be improved to create age-friendly rural communities and to cultivate a social care culture in rural society. The construction of a sustainable mechanism for voluntary care and mutual assistance for the elderly also needs to be in place to promote the construction of rural age-friendly communities and the further development of rural AIP models in China.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Social Science Fund of Beijing (Grant No. 22SRB007). We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Prof. Shiufai Wong for organising the conference on AIP and his invaluable comments on the first draft of this paper. Our thanks also go to the editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Manuscript received on 30 November 2022. Accepted on 24 July 2023.

References

ANSELL, Chris, and Alison GASH. 2008. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory18: 543-71.

AO, Yibin, Yuting ZHANG, Yan WANG, Yunfeng CHEN, and Linchuan YANG. 2020. “Influences of Rural Built Environment on Travel Mode Choice of Rural Residents: The Case of Rural Sichuan.” Journal of Transport Geography 85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102708

BENNETT, Andrew. 2010. “Process Tracing and Causal Inference.” In Henry BRADY, and David COLLIER (eds.), Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards (2nd ed.). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. 207-19.

BOND, Megan, Jeffrey R. BROWN, and James WOOD. 2017. “Adapting to Challenge: Examining Older Adult Transportation in Rural Communities.” Case Studies on Transport Policy 5: 707-15.

BOYLE, Alexandra, Janine L. WILES, and Robin A. KEARNS. 2015. “Rethinking Ageing in Place: The ‘People’ and ‘Place’ Nexus.” Progress in Geography 34: 1495-511.

BUFFEL, Tine, Sophie HANDLER, and Chris PHILLIPSON (eds.). 2018. Age-friendly Cities and Communities: A Global Perspective. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

CALLAHAN, James J. (ed.). 1993. Aging in Place. London: Routledge.

CHEN, Sheying. 2012. “Historical and Global Perspectives on Social Policy and ‘Ageing in Community.’” Ageing International 37: 1-15.

DAVEY, Judith, Virginia DE JOUX, Ganesh NANA, and Mathew ARCUS. 2004. Accommodation Options for Older People in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Wellington: Centre for Housing Research Aotearoa New Zealand.

FANG, Lijie 房莉傑, and ZHOU Pan 周盼. 2020. “‘多元一體’的困境: 我國養老服務體系的一個理解路徑” (“Duoyuan yiti” de kunjing: Woguo yanglao fuwu tixi de yige lijie lujing, The dilemma of “integrating plurality”: An approach to understanding the elder care system of China). Jiangsu xingzheng xueyuan xuebao (江蘇行政學院學報) 1: 60-6.

FRANK, Jacquelyn Beth. 2002. The Paradox of Aging in Place in Assisted Living. Westport: Prager Publishers.

GARDNER, Paula J. 2011. “Natural Neighbourhood Networks: Important Social Networks in the Public Lives of Older Adults Aging in Place.” Journal of Aging Studies 25: 236-71.

GEORGE, Alexander L. 2019. “Case Studies and Theory Development: The Method of Structured, Focused Comparison.” In Dan CALDWELL (ed.), Alexander L. George: A Pioneer in Political and Social Sciences. Cham: Springer. 191-214.

JIANG, Yuzhen 薑玉貞. 2019. “社會養老服務多元主體治理模型建構與分析: 基於紮根理論的探索性研究” (Shehui yanglao fuwu duoyuan zhuti zhili moxing jiangou yu fenxi: Jiyu zhagen lilun de tansuo xing yanjiu, Construction and analysis of multi-subject governance model of social care for the aged: Based on the exploitive research of grounded theory). Lilun xuekan (理論學刊) 2: 143-51.

HANCOCK, Shaun, Rachel WINTERTON, Clare WILDING, and Irene BLACKBERRY. 2019. “Understanding Ageing Well in Australian Rural and Regional Settings: Applying an Age-friendly Lens.” Australian Journal of Rural Health 27: 298-303.

JOSEPH, Alun E., and David R. PHILLIPS. 1999. “Ageing in Rural China: Impacts of Increasing Diversity in Family and Community Resources.” Journal of Cross-cultural Gerontology 14: 153-68.

KEELING, Sally. 1999. “Ageing in (a New Zealand) Place: Ethnography, Policy and Practice.” Social Policy Journal of New Zealand 13: 95-114.

IECOVICH, Esther. 2014. “Aging in Place: From Theory to Practice.” Anthropological Notebooks 20: 21-32.

LAWLER, Kathryn. 2001. Aging in Place: Coordinating Housing and Health Care Provision for America’s Growing Elderly Population. Washington: Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University; Neighbourhood Reinvestment Corporation.

LEWIS, Camilla, and Tine BUFFEL. 2020. “Aging in Place and the Places of Aging: A Longitudinal Study.” Journal of Aging Studies 54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2020.100870

LI, Bin, and Sheying CHEN. 2010. “Ageing, Living Arrangements, and Housing in China.” Ageing International 36: 463-74.

LIU, Hongqin 劉紅芹, and BAO Guoxian 包國憲. 2012. “政府購買居家養老服務的管理機制研究: 以蘭州市城關區‘虛擬養老院’為例” (Zhengfu goumai jujia yanglao fuwu de guanli jizhi yanjiu: Yi Lanzhou shi Chengguan qu “xuni yanglaoyuan” weili, Research on the management mechanism of government purchasing home-based elderly services: Taking the “virtual nursing home” in Chengguan District, Lanzhou City as an example). Lilun yu gaige (理論與改革) 1: 67-70.

LIU, Nina 劉妮娜. 2019. “農村互助型社會養老: 中國特色與發展路徑” (Nongcun huzhu xing shehui yanglao: Zhongguo tese yu fazhan lujing, Mutual-aid social care in rural areas: Chinese characteristics and development path). Huanan nongye daxue xuebao (shehui kexue ban) (華南農業大學學報(社會科學版)) 1: 121-31.

LUO, Yan 羅豔, and SHI Renbin 石人炳. 2016. “虛擬養老院服務品質評價指標體系初探” (Xuni yanglaoyuan fuwu pinzhi pingjia zhibiao tixi chutan, Discussion on virtual nursing home service quality and evaluation index system). Huazhong kejidaxue xuebao (shehui kexue ban) (華中科技大學學報(社會科學版)) 5: 123-9.

MEANS, Robin. 2007. “Safe as Houses? Ageing in Place and Vulnerable Older People in the UK.” Social Policy and Administration 41: 65-85.

NIE, Peng, Yan LI, Lanlin DING, and Alfonso SOUSA-POZA. 2021. “Housing Poverty and Healthy Aging in China: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189911

SALIME, Samira, Christophe CLESSE, Alexis JEFFREDO, and Martine BATT. 2022. “Process of Deinstitutionalization of Aging Individuals with Severe and Disabling Mental Disorders: A Review.” Front Psychiatry 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.813338

SCHARLACH, Andrew E., and Amanda J. LEHNING. 2013. “Ageing-friendly Communities and Social Inclusion in the United States of America.” Ageing and Society 33: 110-36.

WANG, Xuehui, and Zhan HU. 2021. “Developments in China’s Governance of its Aging Society: Evidence from Aging Policies between 1982 and 2017.” International Journal of Social Welfare 30: 443-52.

WILES, Janine L., Annette LEIBING, Nancy GUBERMAN, Jeanne REEVE, and Ruth E. S. ALLEN. 2012. “The Meaning of ‘Aging in Place’ to Older People.” The Gerontologist 52: 357-66.

WILSON, Nathaniel W., Ian D. COUPER, Elma de VRIES, Steve REID, Therese FISH, and Ben MARAIS. 2009. “A Critical Review of Interventions to Redress the Inequitable Distribution of Healthcare Professionals to Rural and Remote Areas.” Rural Remote Health 9: 1-21.

World Bank, and Development Research Centre of the State Council, the People’s Republic of China. 2022. “Four Decades of Poverty Reduction in China: Drivers, Insights for the World, and the Way Ahead.” Washington: World Bank.

World Health Organisation. 2007. Global Age-friendly Cities: A Guide. Geneva: World Health Organisation. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43755

YANG, Jinghui 楊靜慧. 2016. “互助養老模式: 特質, 價值與建構路徑” (Huzhu yanglao moshi: Tezhi, jiazhi yu jiangou lujing, Mutual-help retirement: Characteristics, values, and construction methods). Zhongzhou xuekan (中州學刊) 3: 73-8.

YI, Fujin, Chang LIU, and Zhigang XU. 2019. “Identifying the Effects of Migration on Parental Health: Evidence from Left-behind Elders in China.” China Economic Review 54: 218-36.

YU, Jingyu, Guixia MA, and Shuxia WANG. 2021. “Do Age-friendly Rural Communities Affect Quality of Life? A Comparison of Perceptions from Middle-aged and Older Adults in China.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 72-83.

YUAN, Xin 原新, LIU Zhixiao 劉志曉, and JIN Niu 金牛. 2020. “從追趕到超越: 中國老齡社會的演進與發展之路” (Cong zhuigang dao chaoyue: Zhongguo laoling shehui de yanjin yu fazhan zhilu, From catching up to surpassing: The evolution of China’s ageing society). Xinjiang shifan daxue xuebao (zhexue shehui kexue ban) (新疆師範大學學報(哲學社會科學版)) 2: 91-9.

YUAN, Xin 原新, and ZHOU Pingmei 周平梅. 2019. “農村‘整合式-網格化’養老模式探索研究” (Nongcun “zhengheshi-wanggehua” yanglao moshi tansuo yanjiu, Exploratory research on the integrative grid-based elderly care model in rural China). Hebei xuekan (河北學刊) 4: 178-84.

ZHANG, Ziqi 張子琪. 2020. “國際視野下‘原居安老’研究的歷史回顧與知識圖譜” (Guoji shiye xia “yuanju anlao” yanjiu de lishi huigu yu zhishi tupu, A review and knowledge mapping of the study on “ageing in place” from the international perspective). Xin jianzhu (新建築) 1: 118-22.

ZHENG, Xiongfei 鄭雄飛, and WU Zhenqi 吳振其. 2022. “孝而難養與守望相助: 農村空巢老人互助養老問題研究” (Xiao er nanyang yu shouwang xiangzhu: Nongcun kongchao laoren huzhu yanglao wenti yanjiu, Being filial but having difficulties to take care and support each other: A study on the problems of mutual-support for the empty-nest elderly in rural China). Neimenggu shehui kexue (內蒙古社會科學) 2: 147-54.

ZHU, Huoyun 朱火雲, and DING Yu 丁煜. 2021. “農村互助養老的合作生產困境與路徑優化: 以X市幸福院為例” (Nongcun huzhu yanglao de hezuo shengchan kunjing yu lujing youhua: Yi X shi xingfuyuan wei li, Coproduction dilemma and path optimisation of mutual-aid for older people in rural areas: An example from Happiness Home in X City). Nanjing nongye daxue xuebao (shehui kexue ban) (南京農業大學學報(社會科學版)) 2: 62-72.

[1] China’s targeted absolute poverty reduction strategy was aimed at addressing the problems of rural people’s access to basic infrastructure, communities’ living conditions, and basic public service provision (World Bank Group and Development Research Centre of the State Council, the People’s Republic of China 2022).

[2] World Health Organisation, “Measuring the Age-friendliness of Cities: A Guide to Using Core Indicators,” 16 February 2015, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509695 (accessed on 19 August 2022).

[3] State Council 國務院, “國務院關於加快發展養老服務業的若干意見” (Guowuyuan guanyu jiakuai fazhan yanglao fuwu ye de ruogan yijian, State council opinion on accelerating the development of the elder care service industry), 6 September 2013, www.gov.cn/xxgk/pub/govpublic/mrlm/201309/t20130913_66389.html (accessed on 19 August 2022).

[4] Data from a local government document provided by the local government official interviewed by the authors.