BOOK REVIEWS

Reconnecting to the Great Civilisation: The Strategy of Revitalising the Hakka Unicorn Dance in Hong Kong’s Hang Hau through the Intangible Cultural Heritage System

Dr Tik-sang Liu is Associate Professor Emeritus in the Division of Humanities at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Clear Water Bay, Kowloon, Hong Kong (hmtsliu@ust.hk).

Introduction

The Hakka unicorn dance in Hang Hau, Hong Kong, was named as an item on the Chinese national list of intangible cultural heritage in 2014,[1] indicating the dance as an important cultural heritage to be safeguarded. The attainment of intangible cultural heritage (ICH) status was considered to be a great achievement by local Hakka villagers, who had been worried about the gradual vanishing of their ancestral tradition in modern times. The naming of the Hakka unicorn dance in Hong Kong as a national ICH item followed the Chinese government’s joining of UNESCO’s initiative of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (hereafter ICH Convention).[2] As part of China’s larger ICH project, the Hong Kong government began to safeguard ICH in Hong Kong in 2006 (Chau 2011; Liu 2011a, 2011b, 2021; Chan 2018), while at the same time nominating their local items to be included on Beijing’s national list[3] (Kuah and Liu 2016). The criteria and process for Hong Kong items to be included on the national list was conducted in adherence to China’s ICH law, which required that items “reflect the distinguished traditional culture of the Chinese nation and have historical, literary, artistic, or scientific value.”[4] The Hang Hau Hakka unicorn dance was one of the four items in the second batch nominated by Hong Kong for Beijing’s consideration and was successfully enlisted in 2014.[5] Making use of this newly gained prestigious status, the Hakka villagers in Hang Hau have gradually reestablished their unicorn troupes, and in the process have sought to emphasise the authentic meanings of the dancing acts, proclaiming the dance to have long been part of the great traditional Chinese civilisation.

Unicorn dance turns ICH

The Hakka unicorn dance was brought to Hong Kong by Hakka migrants as they moved from Southern China and began to settle in different parts of Hong Kong in the eighteenth century. Since then, the unicorn dance has been a major component in ritual and communal events in Hong Kong’s Hakka villages,[6] as well as a performative cultural activity in festive events in Hong Kong.[7] Hong Kong’s Hakka unicorn dance was once part of a tradition shared with the Hakka people in neighbouring Guangdong Province[8] – where the ancestors of the Hang Hau Hakka people originated – but became disjoined after 1949 when local traditional activities were labelled as “feudal superstitions” and were banned in mainland China (Overmyer 2001; You 2020). After that, Hong Kong and some Chinese diasporas became the few places that still maintained this dancing tradition. Under British colonial rule in Hong Kong, the Hakka villagers could maintain their traditions, but dancing exchanges with villagers across the border had stopped for decades. Such exchanges have gradually resumed since the introduction of the category of ICH.[9]

Despite being among the few places where the Hakka unicorn dance tradition lived on, Hong Kong villages have experienced significant difficulties in maintaining the dance in past decades, with many local dance troupes becoming inactive due to the lack of young participants to carry on the tradition. In the few cases when young players were involved, they were more keen on learning new dancing patterns and styles, and the maintenance of traditional dancing patterns was not a priority for them. At the time when the unicorn dance’s national ICH application was prepared in the early 2010s, this local tradition was already under threat of vanishing. From the perspective of the villagers, the new national list status undoubtedly came at the right moment to give the general public a sense of the importance of conserving the Hakka unicorn dance.

According to the UNESCO ICH Convention, participant countries must identify their local cultural traditions and prepare respective inventories and lists for the purpose of safeguarding these practices. In this sense, the ICH list-making process has become a state project that produces a master scheme guiding the direction of cultural conservation in how these traditions would be conserved (Liu 2014). When developing their own ICH system under the political arrangement of “one country, two systems,” the principle is that Hong Kong can create its separate list of local ICH items and nominate some of its items to be included on the national list. In 2013, the Hang Hau villagers established a Joint Association[10] to conserve their unicorn dance tradition and proposed it to the Hong Kong government for the national application. The author was invited to help with the preparation of the application, which was evaluated and endorsed by the government-appointed Advisory Committee and was nominated to Beijing for the 2014 exercise.[11]

In the last ten years, the Hang Hau villagers have gradually reestablished their unicorn troupes under both the ICH system in Hong Kong and China’s national ICH framework (Liu and Yuan 2018; Ye and Huang 2019). With funding support from the government, a series of training sessions were arranged for young villagers, school students, and the public to learn the unicorn dance. As observed by the author, the unicorn dance masters always emphasised the cultural meanings of the basic dancing rules in these training sessions; they provided learners with their interpretations of how the dance embodied traditional Chinese values. Seen from an etic perspective, what these masters have done is to create a standardised meaning of the dance on one hand, and to map their local traditions onto to the dominant national narrative on the other. By demonstrating how their tradition was part of the “distinguished traditional culture of the Chinese nation,” villagers reconnected local values to the great Chinese civilisation as a strategy to legitimise the position of the Hang Hau unicorn dance within China’s national ICH framework under the “one country, two systems” arrangement.

Hakka migrants in Hang Hau

Comprehending the social functions of the Hang Hau Hakka unicorn dance requires a contextual understanding of Hakka villagers’ geographical settlement and way of life. The landscape of Hong Kong consists of the flatland plains in the western part and the hilly areas on the eastern side, with the plain areas that had fertile soil and riverine water supply being the ideal location for paddy rice cultivation. For many centuries, the fertile flatland areas had been occupied by Punti people (Cantonese speakers), who had also established their lineage organisations to take care of their own security and welfare in the region (Baker 1968; Potter 1968; Watson J. 1975; Watson R. 1985). When the Hakka people first came to Hong Kong from central Guangdong during the eighteenth century, they learned that the ideal farmlands were already occupied and thus unavailable for their own settlement. They eventually settled in the peripherals of the flatlands, in valleys or narrow flatlands in the mountainous areas, forming small and isolated settlements all over Hong Kong (Blake 1981; Constable 1994; Lau 2007; Johnson and Johnson 2019).[12]

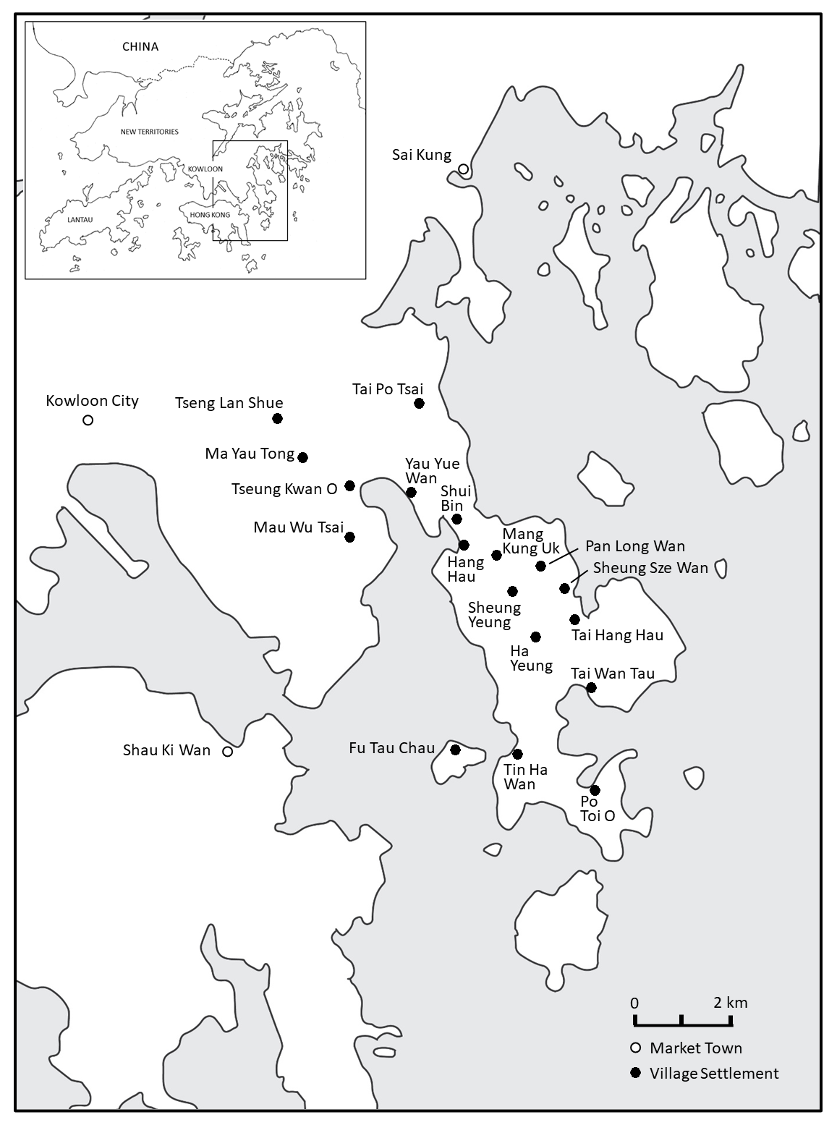

The Hakka ancestors of the Hang Hau villagers chose to settle in the Clear Water Bay Peninsula in the eastern part of Hong Kong[13] (see Figure 1) (Hayes 1974; Siu 1986: 170-82; Ma 2002; Ma et al. 2003; Ye 2018). In these hilly areas, villagers could not grow sufficient rice for their own consumption, and had to supplement rice with sweet potatoes. As their settlements were not far away from the coast, they also fished and collected shellfish to supplement their diets.

Figure 1. Map of Hang Hau villages in the 1970s

Credit: author.

The remote locations of their settlements also meant that villagers had to make frequent lengthy trips to the other side of the mountain to reach the marketplace. If the villagers wanted to buy their daily necessities, the closest market town was Kowloon City, which was about 15 kilometres away. In the past, villagers in the middle part of the peninsula had to wake up in the early morning and walked all the way to Kowloon City while carrying firewood on their shoulders. They would use the income from selling firewood to buy the daily items that they needed, and then walk back to their respective villages. This trip would typically require a whole day.

Since villagers had no choice but to settle in remote areas that were exposed to occasional attacks from sea-bandits (Siu 1986: 151-4; Antony 2003), the villages were often built at some distance from the seaside to reduce the risk of direct robbery by sea-bandits. This decision to settle in remote areas, however, also meant that they would not receive sufficient protection from the imperial government and had to take care of their own village affairs. As most of the villages were small in size,[14] they also had no resources to hire helping hands from the outside. Although lineage organisations were established in some larger settlements, they did not play a significant role in communal activities.[15] According to the senior villagers, all members of the community were expected to help in communal events, especially during weddings and funerals. At the same time, village elders trained younger boys in martial arts to form the villages’ self-defence force; these boys all became performers in unicorn dances and took part in the village’s communal and ritual events in that capacity. The self-defence force thus became an informal association formed by male villagers to serve the security, ritual, and entertainment needs of the local community.

A unicorn with different appearances

The unicorn (麒麟: qilin in Mandarin,[16] ki2 lin2 in Hakka) is one of the four mythical animals in Chinese ancient legends – the other three being the dragon, the phoenix, and the turtle. People believe that these sacred animals would bring them luck and fortune. In a popular dictionary source, the unicorn’s appearance is like a large deer with a dragon head, an ox tail, a horse’s hoofs, a horn (or pair of horns) on its head, colourful hair scales on its back, and yellow hair on its abdomen.[17] It is a benevolent beast, a vegetarian animal with a gentle temperament that would not hurt any living thing. It is said that when Confucius was born, a unicorn appeared and spit out a jade tablet with a prophecy written on it. This legend depicts the unicorn as a literate animal, and its presence signifies the birth of a saint into the world (Eberhard 1986: 302-4).

In their local customs, Guangdong’s Hakka people have turned this mythical beast into reality by making a unicorn costume that consists of both a head and a body that would be worn by two dancers. The unicorn head is made of paper and bamboo strips and the body is represented by a piece of long cloth. The dancers follow percussion music to dance in rituals and ceremonies.

Figure 2. A unicorn troupe

Credit: author.

The appearance of the Hang Hau Hakka unicorn differs from traditional understandings of the features of the unicorn in several aspects.[18] The head of the Hakka unicorn has a stuck-out forehead and a short nose, which does not resemble the legendary dragon head that has no forehead and a long nose. In the drawings of the last several centuries, most of the unicorns depicted have a pair of horns that resemble those of deer, unlike the ones of the Hakka unicorn (Xu 2002; Zheng 2012). Besides this, the Hakka unicorn is much more colourful than its traditional depiction, and is imprinted with additional auspicious patterns. In terms of the sex of the unicorn, the Hang Hau villagers disagree with the dictionary explanation that both male and female unicorns exist; they insist that their unicorns are all males.

The villagers in Hang Hau have their special ways to decorate their unicorns. The Daoist taiji 太極 diagram, representing the universe, is printed on the unicorn’s forehead. A shawl with five cloth layers, in five different colours symbolising the Daoist five elements (wuxing 五行),[19] is attached to the back of the unicorn’s head, forming the shoulder of the unicorn. A popular auspicious saying, “the wind and rain come in their time” (fengdiao yushun 風調雨順) is sewn onto the fabric of the shawl as a decoration.

Figure 3 and 4. Unicorn head

Credit: author.

Unicorn dance in Hang Hau

In the past, practicing and watching unicorn dance was one of the villagers’ major sources of entertainment. In Hang Hau, boys started their martial arts training at an early age, with village elders acting as their instructors. The front yard of the ancestral hall was the venue for this martial arts training, of which the unicorn dance was a crucial part. Unicorn heads were once precious items[20] that would only be used in actual rituals or public performances, and bamboo baskets would be used in training sessions as substitutes. The boys would get very excited if they were allowed to play with the real unicorn heads – an implicit endorsement of their dancing skills.

In the eyes of the villagers, the unicorn is a sacred animal that embodies a combination of all of their ideal expectations of life. People believe that unicorns can expel ritual pollution,[21] ward off evil spirits, and bring fortune to the participants. The unicorn dance is an essential element in all the major rituals and communal ceremonies, for examples in wedding rituals, birthday celebrations, opening rituals for renovated ancestral halls and newly built houses, as well as for welcoming village guests.

During the Lunar New Year, the unicorn troupe will perform the unicorn dance at every house in the village to expel evil spirits and to bring prosperity to the villagers, marking the new beginning of an annual cycle. A man’s wedding is considered an important event in a village. The unicorn troupe receives the bride at the entrance of the village and leads her to the groom’s house.[22] On the way, the musicians of the unicorn troupe would switch to striking another piece of percussion music, “the gong of having a baby” (tiandingluo 添丁鑼), as a blessing to the new couple for having a baby soon. During the whole wedding ceremony, loud percussion music serves to inform the villagers of the arrival of a new bride.

When a temple festival[23] or a communal event is organised by friends of the village,[24] the village’s unicorn troupe will pay a visit to celebrate. This is known as the “unicorn leaving its shed” (qilin chupeng 麒麟出棚) or “unicorn excursion.” At the event venue, the unicorn troupe will perform the “unicorn jump” (qilintiao 麒麟跳) and martial arts for the public audience. The unicorn jump is a dance custom of “plucking the greens” (caiqing 採青) to bring fortune for the event.[25] In the second part, all members of the unicorn troupe take turns performing martial arts for the spectators, and the event usually concludes with the performance of the master. A performance is usually completed within 30 minutes. These external visits serve an important role in maintaining the village’s social networks.

Figure 5. A unicorn jump performance

Credit: author.

How to dance a unicorn

A unicorn costume includes a papier-mâché head and a cloth body. The unicorn is danced by two people, one for the head and the other for the rear end. In Hang Hau’s unicorn dances, three people are responsible for the percussion music, including a cymbal, a gong, and a drum. The gong produces a steady high-tone sound, and together with the drum serves to keep the beat as well as to mark the beginning and the end of the performance. The rapid and continuous crashing of the cymbals produces loud and explosive sounds that match the rhythmic dancing patterns of the unicorn. The cymbal player therefore also has to alter the speed and intensity of the crashes to complement the unicorn’s movement. At the same time, the unicorn should also dance according to the rhythm of the percussion music, so the music also has the function of directing the movement of the unicorn – a quicker rhythm would push the unicorn to move faster. However, the musicians need to adjust the rhythm or change the pattern of the music if the unicorn dancers change their style of movement. The dancers and the musicians therefore work in dialogue – the musicians need to adapt their music according to the real-time situation of the event. During the performance, there is always room for the troupe members to show off their dancing and music skills. A dancing performance is considered a good one when the dancing patterns and percussion music are in sync with each other, with the musicians and the dancers working seamlessly together.

During the dance, the two unicorn dancers have to hide inside the unicorn head and under the rear end, meaning that the dancer of the unicorn’s head can only see the exterior through the tight space of the unicorn’s mouth, while the dancer at the back can only follow the movement of the head dancer. Due to limited vision, the two dancers often cannot comprehend the total situation of the site. The master of the troupe therefore becomes the leader to guide the movement of the unicorn. In critical situations, he has to stand next to the unicorn head to instruct the unicorn’s movement specifically.

The villagers understand that the unicorn is a cautious animal, which would not rush to approach its targets but only do so slowly and carefully – that is the personality of the unicorn to be expressed by the dancers. In addition to the basic footwork, a dancer should also develop his own dancing style. For example, a master explained that he tried to mimic the movement of roosters in his dance. Although there are basic rules for dancing a unicorn, there is room for the dancers to develop their own styles as well as specific styles for different villages.

A unicorn dance requires a high level of physical strength, and the basic footwork of Chinese martial arts is essential for dancing the unicorn. This is the reason why martial arts training is always a crucial part of unicorn dancing. On average, the two unicorn dancers need to be replaced every five to ten minutes to avoid exhaustion. If the performance is a long one, a number of people are needed to take turns in dancing the unicorn. The same goes for the musicians: the percussion instruments also require physical strength to play, as they are large and heavy. Although there are only five positions in a unicorn dance troupe for both the dancing and the music, it often requires eight to ten people to perform a dance together.

The signature styles of the unicorn dance of each village can be seen in both the costume design and the dancing patterns. In the past, villagers crafted their own unicorn heads, and they would often incorporate their own characteristics and preferred colours onto the design. While some villages invited masters from the outside to teach their young men martial arts and unicorn dancing skills, the elders would still teach their fellow villagers their own distinct movement patterns. It is a common practice that each village maintains some of its own characteristics in the dancing. In sum, there are differences in terms of the movements of the dance, the rhythm of the percussion music, and the decorations on the unicorn costume among different villages.

Essential dancing rules

According to the masters of several unicorn troupes, the unicorn dance must follow certain dancing rules, and a fight between the troupes could happen if these rules are violated during an event or a performance. The most important basic principles are summed up as follows:

(i) Greeting

When a unicorn visits a respectable place or meets a respectable person, the unicorn should always pay homage to the place and greet the person. The basic greeting gesture is to knock the unicorn head three times, which is known as worship (canshen 參神). When two unicorn troupes run into each other, both should pay homage and greet each other, first by knocking the unicorn heads three times, followed by the masters of the two troupes exchanging “invitation cards” (baitie 拜帖) that carry the names of the unicorn troupes. Then the two unicorns would perform together for a few minutes.

Figure 6. Two unicorn troupes greeting each other

Credit: author.

(ii) A low gesture

When two unicorns play with each other, the basic principle is to show one’s respect to the other, which is done by taking a bow. Each unicorn attempts to bow its head to a point that is lower than the head of the other. Since the same rule applies to both unicorns, it often results in the situation where the two unicorns are almost crawling on the ground.

(iii) The left as the superior side

The distinction has to be made between the left-hand side and the right-hand side of the unicorn’s movements – the left-hand side is always superior. When a unicorn enters an ancestral hall or a temple, it should always start with the left-hand side.[26] However, there are ambiguities as to whose left-hand side it is, as this could be understood from the positions of both the guests and the host. Some interpret the rule as referring to the unicorn’s left-hand side when entering the ancestral hall, which is also the host’s right-hand side, as this means that the unicorn is being humble to the host. However, another view is that the unicorn’s right-hand side should be the side that expresses one’s humble position. It seems that different villages have different understandings of this rule.

(iv) Visiting sacred places

When a unicorn arrives at a village, it should first visit the earth god shrines, and then the ancestral halls and local temples – the sacred and collective symbols of the village community. This custom shows that the unicorn is an educated and a polite animal, which acts in ways that respect villagers and the existing social rules and hierarchies.

(v) Reading the couplet

A couplet (duilian 對聯) is a pair of lines of poetry posted on the two sides of the entrance of an ancestral hall. When a unicorn visits an ancestral hall, one of the dancing patterns is to read the couplet (dudui 讀對). The unicorn needs to dance in front of the couplet as if reading the Chinese characters, an action to demonstrate that the unicorn is literate. Since the first line of the couplet is placed on the unicorn’s right-hand side, the dance starts there.

(vi) Generating a coin

People believe that the round-shape pattern of an ancient Chinese cash coin (jinqian 金錢) represents fortune and wealth. One of the unicorn dancing patterns is to dance in circles resembling the shape of a coin. When two unicorns meet and dance with each other, they dance in circles, which also creates jinqian. When a unicorn enters an ancestral hall, it needs to dance around the two pillars of the protective door (pingfeng 屏風) that separates the front and the main hall. The route of the dance is shaped like the numerical character 8, which symbolises the shape of two ancient coins. This dance pattern is known as “penetrating the protective door” (chuan pingfeng 穿屏風) or “penetrating the coins” (chuan jinqian 穿金錢).

(vii) Creating a knot and unknotting

When a unicorn performs a dance, its movements create an invisible track, some of which resembles the pattern of a knot (jie 結) being tied by a piece of string. From the villagers’ perspective, a knot symbolises constrictions that might retain negative impacts. Therefore, these knots must be untied before the performance is completed so as to release the negative impacts created during the dance. For example, when a unicorn visits an ancestral hall, its movement inside the hall creates many knots. After finishing its worship at the ancestral tablet, the unicorn needs to leave backwards on the same route that it took when entering the hall. The retreating pattern would serve to untie the knots (jiejie 解結). In the same logic, when two unicorns meet each other and dance together, the dancing patterns may form invisible knots as well. The two unicorns would then need to dance in a reversed manner to untie the knots for completing the performance.

(viii) Flattening the edges

Since the villagers believe that the unicorn could expel evil forces, during a unicorn dance, the dancers may lean the unicorn’s body against other objects. This movement is known as “flattening the edges” (shengjiao 省角). Villagers see edges and sharp objects as obstacles that should be flattened, and this is symbolically carried out by the unicorn’s leaning movements.

(ix) Plucking the greens

When a unicorn troupe gives a public performance during an outside visit, the host of the external party would often invite the visiting unicorn to perform the play of “plucking the greens.” A lettuce and a red envelope with some cash are often placed on the ground at the centre of an open space for the visiting unicorn to “eat,” which is also known as “eating the greens” (shiqing 食青) – a highlight of the performance. The unicorn would dance around the lettuce and finally eat the lettuce in a symbolic manner. For this part of the performance, there is flexibility regarding the duration of the play. It can be done in a few minutes, or a longer period of time if the troupe wants to make an elaborated performance. In the end, the unicorn would keep the red envelope but return the stem of the lettuce to the host. This act of giving the lettuce stem back is to ritually bring fortune to the host, as the homophone of lettuce stem (caitou 菜頭) is “symbol of fortune” (caitou 彩頭).

A total organisation for small villages

From the aforementioned, it is clear that the unicorn dance was not only a core part of the martial arts training that young villagers received for the purpose of forming the village’s self-defence force, but also a fundamental element of many social functions and services in the village community. One of these is the ritual services that were a mandatory element in communal and major life-cycle rituals (Johnson and Johnson 2019).

Entertainment and the maintenance of social networks are two other important functions that the unicorn dance fulfilled. More than simply a ritual, unicorn excursions to communal festivals were a spectacle that villagers enjoyed watching. The external visits helped to maintain the village’s social networks and held together robust relationships among small neighbouring villages. It was necessary for the village’s young men to know how to perform the dance. This was why the unicorn dance was always incorporated into the training of martial arts.

It was often the case that local elders coordinated the young men serving the village community. The organisation of the unicorn dance addressed the basic needs of these remote villages: security and ritual services. The unicorn dance was an integral part of a modest way of life in which villagers had to depend on each other in a remote setting with very limited support from the imperial government.

In the small villages of Hang Hau, they developed this kind of system surrounding the unicorn dance to meet their own needs in past centuries. Since a small number of villagers could perform the dance and finish the job of a regular ritual, a small-sized village would have no difficulty maintaining a unicorn troupe before the 1970s. What was embedded in each unicorn dance performance was therefore the intricate relationships between villages as well as the social hierarchy among the participants as part of the larger social organisation of the village.

A vanishing tradition

The tradition of the unicorn dance experienced significant decline in the 1960s and 1970s, as Hong Kong’s agricultural production was affected by the shortage of riverine water[27] and the competition of imported agricultural produce. At the same time, Hong Kong’s economy began to take off, with the industrial sector expanding and in need of an influx of young factory workers. As a result, young people in rural areas began to find job opportunities elsewhere. Many of them left Hong Kong for jobs in Europe (Watson J. 1975), while some moved to the urban areas to join the industrial workforce. This led to a drastic loss of young people in the villages, many of whom were active participants in unicorn dancing, martial arts, and farm work.

Without the young players, the Hang Hau villagers had difficulty maintaining their unicorn dance tradition. In the 1970s, some villagers invited a martial arts master, Liu Zhaoguang 劉兆光, from Shenzhen to teach their children martial arts and the unicorn dance. The arrangement was a success and trained a generation of unicorn dance players.[28] In the 2000s, this generation of players, in their fifties, witnessed the decline of the tradition again and started to form the Traditional Hakka Unicorn Association to conserve their unicorn dance tradition. Their goal was realised by the Hong Kong government’s exercise on nominating local ICH for the national list.

Connecting to the great civilisation

The unicorn is considered one of the four mythical animals in the great Chinese tradition. However, the ancient drawings and the current Hakka unicorn look very different, signalling the changing interpretations of the unicorn from its mythical origins to the customary practices in local villages. Obviously, the Hakka unicorn is a unique dancing tradition developed in Guangdong and brought to Hong Kong by the Hakka migrants. The process of how this local tradition then became re-immersed into the great Chinese narrative and was ultimately accepted as demonstrating “distinguished cultural value” is an important phenomenon in the study of ICH, particularly in the case of Hong Kong and mainland China. China’s initiative to participate in the ICH convention has allowed the country to re-recognise its local cultural traditions that had been denied for many decades after 1949 (You 2020). On Hong Kong’s side, participation in the ICH state project has allowed local traditions to become part of China’s great civilisation again.

One aspect of the connection between the local and the great Chinese civilisation is demonstrated in the emphasis placed by senior villagers on the traditional etiquette that functions as the basic principles that inform or constitute the unicorn dancing rules. It is not difficult to understand that this system of etiquette, such as the need to pay respect at the local temple or ancestral hall when visiting a village, or to bow before another unicorn troupe as the masters make introductions, refers to the expected patterns of behaviour among people in the villages. Over the past hundreds of years, the Hakka people have already integrated these Chinese etiquette principles in the form of dancing rules in their unicorn dance activities, which actually echo their expectations of the social norm. Under the framework of traditional etiquette, the local tradition and the great civilisation – recognised by the Chinese state – are beautifully combined, and the existence and practices of this local dancing tradition are also given a sense of historical and cultural legitimacy (Rawski 1988: 26-9).

By referencing the etiquette system in the great civilisation, the conservation of the unicorn dance has also sought to promote the ideal social structure of the village in the postindustrial era. In the process of revitalisation, it might seem that the villagers are most concerned about the dance as a form of traditional performance, but the senior villagers have also placed great emphasis on the basic rules and the principles of etiquette underlying the dancing rules as a metaphor of village organisation and interpersonal relationships, which have come under serious challenge in the face of urbanisation.

Conclusion

China is a vast country with numerous diverse local traditions. How can we understand the relations among these local traditions? Robert Redfield (1956) suggests that there is the “great tradition,” carried by the gentry, and the “little tradition,” carried by the peasants. The two traditions are interdependent, constituting two halves of one culture. In the Hang Hau case, local tradition and the great Chinese civilisation are not interdependent, but rather have a hierarchical relationship. In China, ICH represents the great Chinese civilisation, and also official measures to reincorporate previously banned local traditions as part of Chinese civilisation. National ICH status becomes a resource for revitalising vanishing local traditions.

In the domain of local religion practices, the imperial government’s ways of control may shed light on our understanding of the Hang Hau case. According to James Watson (1985), the imperial government tried to unify various local practices by defining a standardised and limited number of legitimated deities for the ordinary people to worship. When local societies established their patron deities, they had to pick them from the state category. Local religious activities would then be governed by a standard pantheon, and ideally the local religious activities would thus be unified. In response to this top-down policy, local societies gradually adopted these legitimated deities. However, local societies would often insert local meanings and significance to these state symbols, giving them additional layers of vernacular understanding. This is an obvious strategy, as local traditional communal activities could not be maintained without genuine local support.[29]

The Hakka people in Guangdong Province have maintained their unicorn dance for hundreds of years as the dance was a crucial part of their local social organisation. Although the imperial government did not impose any rules or regulations to restrict the activities of unicorn dances, Hakka societies had nonetheless attempted to give their practices orthodox meanings to legitimise their local customs, claiming that the unicorn is a benevolent beast with Chinese mythical origins. This was in fact the way that this local custom survived imperial rule. However, this cultural tie with Chinese civilisation was terminated when the Communists took over China. Many traditional activities were banned, and Hong Kong’s unicorn dance, as one of those old traditions, became a feudal superstitious activity that could only be maintained outside mainland China.

With the introduction of ICH in 2006, the Chinese government established a new umbrella of “Chinese civilisation” that includes all the “distinguished” local practices within the Chinese state. Under “one country, two systems” principle, China’s national policies can be implemented in Hong Kong. ICH has become the official system that can grant certain Hong Kong local traditions a superior national status. The powerless Hang Hau Hakka villagers made use of this opportunity to revitalise their unicorn dance. During this revitalisation process, they actively assigned orthodox meanings to their unicorn dance, emphasised the Chinese values of their unicorns, and defined their tradition as an inherently authentic Chinese one. A standardised meaning of the cultural value of the unicorn dance was created at the beginning of the ICH project as an attempt to reconnect their local ethnic activity to the dominant Chinese narrative.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Florence Padovani for inviting me to write this article, the Hakka unicorn dance masters in Hang Hau for teaching me the dance, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments.

Manuscript received on 7 September 2022. Accepted on 15 May 2023.

References

AHERN, Emily M. 1978. “The Power and Pollution of Chinese Women.” In Arthur P. WOLF (ed.), Studies in Chinese Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 269-90.

ANTONY, Robert J. 2003. Like Froth Floating on the Sea: The World of Pirates and Seafarers in Late Imperial South China. Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California.

BAKER, Hugh D. R. 1968. A Chinese Lineage Village: Sheung Shui. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

BLAKE, C. Fred. 1981. Ethnic Groups and Social Change in a Chinese Market Town. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

CARRIE, William J. 1936. “Report of the Secretary for Chinese Affairs for the Year 1935.” Administrative Reports for the Year 1935. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer. C1-C70.

CHAN, Selina Ching. 2018. “Heritagizing the Chaozhou Hungry Ghosts Festival in Hong Kong.” In Christina MAAGS, and Marina SVENSSON (eds.), Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. 145-67.

CHAU, Hing Wah. 2011. “Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Hong Kong Experience.” In Tik-sang LIU (ed.), Intangible Cultural Heritage and Local Communities in East Asia. Hong Kong: South China Research Centre, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology; Hong Kong Heritage Museum. 121-33.

COHEN, Myron L. 1996. “The Hakka or ‘Guest People’: Dialect as a Sociocultural Variable in Southeastern China.” In Nicole CONSTABLE (ed.), Guest People: Hakka Identity in China and Abroad. Seattle: University of Washington Press. 36-79.

CONSTABLE, Nicole. 1994. Christian Souls and Chinese Spirits: A Hakka Community in Hong Kong. Berkeley: University of California Press.

—— (ed.). 1996. Guest People: Hakka Identity in China and Abroad. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

DING, Shiliang 丁世良, and ZHAO Fang 趙放 (eds.). 1991. 中國地方誌民俗資料彙編(中南卷) (Zhongguo difangzhi minsu ziliao huibian (zhongnan juan), A collection of information on folklore from local gazetteers in China (southern and central volumes)). Beijing: Shumu wenxian chubanshe.

EBERHARD, Wolfram, 1986. A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. London: Routledge.

HAYES, James. 1974. “The Hong Kong Region: Its Place in Traditional Chinese Historiography and Principal Events since the Establishment of Hsin-An County in 1573.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch 14: 108-35.

——. 2012. The Great Difference: Hong Kong’s New Territories and its People 1898-2004. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

JIANG, Wei Chi 姜偉池. 2014. 我不是師傅: 一代醒獅之路 (Wo bushi shifu: Yidai xingshi zhilu, I am not a master: A generation’s road of lion dance). Hong Kong: Joint Publishing (H.K.).

JOHNSON, Elizabeth Lominska, and Graham E. JOHNSON. 2019. A Chinese Melting Pot: Original People and Immigrants in Hong Kong’s First “New Town.” Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

KUAH, Khun Eng, and Zhaohui LIU (eds.). 2016. Intangible Cultural Heritage in Contemporary China: The Participation of Local Communities. London: Routledge.

LAU, Yee Cheung 劉義章 (ed.). 2007. 香港客家 (Xianggang kejia, Hakkas in Hong Kong). Nanning: Guangxi shifan daxue chubanshe.

LIU, Jiyao 劉繼堯, and YUAN Zhancong 袁展聰. 2018. 武舞民間: 香港客家麒麟研究 (Wuwu minjian: Xianggang kejia qilin yanjiu, Folk martial arts and dance: A Study of Hakka unicorn in Hong Kong). Hong Kong: Commercial Press.

LIU, Tik-sang 廖迪生. 1999. “地方認同的塑造: 香港天后崇拜的文化詮釋” (Difang rentong de suzao: Xianggang tianhou chongbai de wenhua quanshi, The construction of local identity: The cultural interpretation of Tin Hau cult in Hong Kong). In LAI Chi-tim 黎志添(ed.), 道敎與民間宗敎硏究論集 (Daojiao yu minjian zongjiao yanjiu lunji, Daoism and popular religion). Hong Kong: Xuefeng wenhua shiye. 118-34.

——. 2003. “A Nameless but Active Religion: An Anthropologist’s View of Local Religion in Hong Kong and Macau.” The China Quarterly 174: 373-94.

——. 2011a. “Intangible Cultural Heritage: New Concept, New Expectations.” In Tik-sang LIU (ed.), Intangible Cultural Heritage and Local Communities in East Asia. Hong Kong: South China Research Center, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology; Hong Kong Heritage Museum. 3-29.

——. 2011b. “‘Tradition’ versus ‘Property Inherited’: The Construction of Meanings for Hong Kong’s Intangible Cultural Heritage.” In Tik-sang LIU (ed.), Intangible Cultural Heritage and Local Communities in East Asia. Hong Kong: South China Research Center, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology; Hong Kong Heritage Museum. 257-82.

——. 2014. “傳統, 認同與資源: 香港非物質文化遺產的創造” (Chuantong, rentong yu ziyuan: Xianggang feiwuzhi wenhua yichan de chuangzao, Tradition, identity and resources: The making of Hong Kong’s intangible cultural heritage). In WEN Jiehua 文潔華 (ed.), 香港嘅廣東文化 (Xianggang [de] Guangdong wenhua, Hong Kong’s Cantonese culture). Hong Kong: Commercial Press. 200-25.

——. 2021. 食盆與盆菜: 非物質文化遺產脈絡中的香港鄉土菜 (Shipen yu pencai: Feiwuzhi wenhua yichan mailuozhong de Xianggang xiangtucai, Eating the dish (sik pun) versus basin dish (pun choi): A Hong Kong indigenous cuisine in the context of intangible cultural heritage). In Foundation of Chinese Dietary Culture 中華飲食文化基金會 (ed.), 食之承繼: 飲食文化與無形文化資產 (Shizhi chengji: Yinshi wenhua yu wuxing wenhua zichan, Inheritance of eating: Dietary culture and intangible cultural heritage). Taichung: Bureau of Cultural Heritage, Ministry of Culture. 179-208.

——. 2022. 香港廟宇(上下卷) (Xianggang miaoyu (shangxia juan), Temples in Hong Kong, (2 volumes). Hong Kong: Wanli jigou.

MA, Muk Chi 馬木池. 2002. “十九世紀香港東部沿海經濟發展與地域社會的變遷” (Shijiu shiji Xianggang dongbu yanhai jingji fazhan yu diyu shehui de bianqian, The economic development and the regional and social changes along Hong Kong’s eastern coast during the nineteenth century). In ZHU Delan 朱德蘭 (ed.), 中國海洋發展史論文集, 第八輯 (Zhongguo haiyang fazhanshi lunwenji, dibaji, Proceedings on the history of China’s maritime development, eighth volume). Taipei: Zhongyang yanjiuyuan Zhongshan renwen shehui kexue yanjiusuo. 73-103.

MA, Muk Chi 馬木池, CHEUNG Siu Woo 張兆和, WONG Wing Ho 黃永豪, LIU Tik-sang 廖迪生, LAU Yee Cheung 劉義章, and CHOI Chi Cheung 蔡志祥 (eds.). 2003. 西貢歷史與風物 (Xigong lishi yu fengwu, History and folklore of Sai Kung). Hong Kong: Sai Kung District Council.

OVERMYER, Daniel L. 2001. “From ‘Feudal Superstition’ to ‘Popular Beliefs’: New Directions in Mainland Chinese Studies of Chinese Popular Religion.” Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 12: 103-26.

POTTER, Jack M. 1968. Capitalism and the Chinese Peasant: Social and Economic Change in a Hong Kong Village. Berkeley: University of California Press.

RAWSKI, Evelyn S. 1988. “A Historian’s Approach to Chinese Death Ritual.” In James L. WATSON, and Evelyn S. RAWSKI (eds.), Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China. Berkeley: University of California Press. 20-34.

REDFIELD, Robert. 1956. Peasant Society and Culture: An Anthropological Approach to Civilisation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

ROSS, S. B. C. 1910. “Report on the New Territories: Northern District.” Administrative Reports for the Year 1909. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer. H1-H4.

SIU, Kwok-kin 蕭國健. 1986. 清初遷海前後香港之社會變遷 (Qingchu qianhai qianhou Xianggang zhi shehui bianqian, Hong Kong’s social change before and after the Qing coastal evacuation). Taipei: Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan.

STRAUCH, Judith. 1983. “Community and Kinship in Southeastern China: The View from the Multilineage Village of Hong Kong.” Journal of Asian Studies 43(1): 21-50.

WATSON, James L. 1975. Emigration and the Chinese Lineage: The Mans in Hong Kong and London. Berkeley: University of California Press.

——. 1982. “Of Flesh and Bones: The Management of Death Pollution in Cantonese Society.” In Maurice BLOCH, and Jonathan PARRY (eds.), Death and the Regeneration of Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 155-86.

——. 1985. “Standardizing the Gods: The Promotion of T’ien Hou (‘Empress of Heaven’) Along the South China Coast, 960-1960.” In David JOHNSON, Andrew J. NATHAN, and Evleyn S. RAWSKI (eds.), Popular Culture in Late Imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press. 292-324.

WATSON, Rubie S. 1985. Inequality among Brothers: Class and Kinship in South China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

WODEHOUSE, Philip Peveril John. 1911. “Report on the Census of the Colony for 1911.” Hong Kong Sessional Papers, 1911. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer.

XU Xiujuan 許秀娟. 2002. “麒麟形象的變遷與中外文化交流的發展” (Qilin xingxiang de bianqian yu Zhongwai wenhua jiaoliu de fazhan, The changing images of the unicorn and the development of China and foreign cultural exchange). Haijiaoshi yanjiu (海交史研究) 1: 57-63.

YE, Deping 葉德平. 2018. 回緬歲月一甲子: 坑口風物志 (Huimian suiyue yi jiazi: Kengkou fengwuzhi, A sixty-year nostalgia: Gazetteer of Hang Hau). Hong Kong: Chuwen chubanshe youxian gongsi.

YE, Deping 葉德平, and HUANG Jingcong 黃競聰. 2019. 西貢. 非遺傳承計劃: 西貢麒麟舞 (Xigong. Feiyi chuancheng jihua: Xigong qilinwu, Sai Kung. Intangible cultural heritage inheritance project: Unicorn dance). Hong Kong: Jinglan wenhua.

YOU, Ziying. 2020. “Conflicts over Local Beliefs: ‘Feudal Superstitions’ as Intangible Cultural Heritage in Contemporary China.” Asian Ethnology 79(1): 137-59.

ZHENG, Jun 鄭軍. 2012. 中國傳統麒麟藝術 (Zhongguo chuantong qilin yishu, Chinese traditional art of the unicorn). Beijing: Beijing gongyi meishu chubanshe.

[1]Intangible Cultural Heritage Office 非物質文化遺產辦事處, “Hakka Unicorn Dance in Hang Hau in Sai Kung,” https://www.lcsd.gov.hk/CE/Museum/ICHO/en_US/web/icho/representative_list_unicorn.html (accessed on 30 June 2022).

[2] UNESCO website, “Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage,” https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 30 June 2022).

[3] China Intangible Cultural Heritage 中國非物質文化遺產網, 中國非物質文化遺產數字博物館, “國家級非物質文化遺產代表性項目名錄” (Guojiaji feiwuzhi wenhua yichan daibiaoxing xiangmu minglu, National list of intangible cultural heritage), https://www.ihchina.cn/project.html#target1 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

[4] National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China 全國人民代表大會, 2011, “中華人民共和國非物質文化遺產法” (Zhonghua renmin gongheguo feiwuzhi wenhua yichan fa, Law of the People’s Republic of China on intangible cultural heritage), www.npc.gov.cn/zgrdw/huiyi/lfzt/fwzwhycbhf/2011-05/10/content_1729844.htm (accessed on 30 June 2022).

[5] Intangible Cultural Heritage Office 非物質文化遺產辦事處, “The Intangible Cultural Heritage of Hong Kong, The Representative List,” https://www.lcsd.gov.hk/CE/Museum/ICHO/en_US/web/icho/representative_list_unicorn.html (accessed on 30 June 2022).

[6] In government reports, the unicorn dance was first reported in the North District in 1909 (Ross 1910: H3), and as part of the official procession celebrating the 25th anniversary of the accession of King George V to the throne in 1935 (Carrie 1936: C12). Johnson and Johnson’s ethnographic research (2019) in Tsuen Wan since the late 1960s reveals that the Hakka unicorn dance had been popular in festival celebrations and for entertainment.

[7] In Hong Kong, lion, dragon, and unicorn dances are popular performances in the celebrations of communal religious festivals (Jiang 2014). See also Intangible Cultural Heritage Office 非物質文化遺產辦事處, “First Intangible Cultural Heritage Inventory of Hong Kong,” https://www.lcsd.gov.hk/CE/Museum/ICHO/documents/10969700/23828638/First_hkich_inventory_E.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2022). For the lion and unicorn dances, people wear the lion or unicorn costume and dance with percussion music. Each troupe consists of around ten players. For the dragon dance, a player holds the pearl and leads the dragon to dance with the percussion music. The dragon head, tail, and serpentine body are supported by poles and held by players. The number of players of a dragon dance depends on the length of the body. There are three forms of unicorn dances in Hong Kong: the Punti (local), the Hoklo (originated from Haifeng, Lufeng, and Shanwei), and the Hakka traditions. These three traditions of unicorn dances have different appearances, patterns of music, and dancing styles.

[8] The 1783 edition of the Gazetteer of Guishan (Guishan xianzhi 歸善縣志) notes that the unicorn dance was performed during wedding rituals (Ding and Zhao 1991: 730). Guishan County, with a large number of Hakka villages, is located next to Hong Kong’s northern border.

[9] On two occasions the author observed Hakka unicorn troupes from Shenzhen, the city in mainland China located next to Hong Kong’s northern border, which were invited for unicorn dance exchanges. The Hong Kong Hakka villagers commented that the dancing styles of the mainland troupes differed from their traditional one.

[10] According to the Joint Association’s chairperson, masters and representatives from all the villages in Hang Hau were invited to jointly establish the association. However, a small number of village leaders did not participate in the national application exercise in the end.

[11] According to UNESCO’s ICH Convention, all the participant countries must keep inventories for the purposes of safeguarding their ICH items. In China, there are separate ICH lists at the province, city, and county levels. To be considered for inclusion on the national list, an item must already be on the provincial list. Since Hong Kong is a special administrative region that does not fall into any specific province, Hong Kong can submit applications directly to Beijing for consideration. In Hong Kong, an ICH Inventory with 480 items was established in 2014 (Intangible Cultural Heritage Office 非物質文化遺產辦事處, “First Intangible Cultural Heritage Inventory (…),” op. cit.). In 2017, a representative list with 20 selected items from the inventory was established to identify “those of high cultural value and with an urgent need for preservation” (Intangible Cultural Heritage Office 非物質文化遺產辦事處, “The Intangible Cultural Heritage of Hong Kong (…),” op. cit.).

[12] For a general discussion of the formation of Hakka as an ethnic category, see Cohen (1996) and Constable (1996).

[13] There are 18 village settlements in the Clear Water Bay Peninsula today, all represented by the “Hang Hau Rural Committee,” an official advisory organisation to the Hong Kong Government. See also Hang Hau District Rural Committee 坑口區鄉事委員會, 2007, 坑口區鄉事委員會 1957-2007: 金禧紀念特刊 (Kengkouqu xiangshi weiyuanhui 1957-2007: Jinxi jinian tekan, Hang Hau District Rural Committee 1957-2007: Golden Jubilee commemorative publication). Hong Kong: Hang Hau District Rural Committee.

[14] After the British took over the New Territories, a census was conducted in 1911 (Wodehouse 1911). In the report, the names of 17 villages match the names of the current settlements in the Clear Water Bay Peninsula. There were 434 residents in the largest settlement, while the smallest one had 12 villagers. The average village population was 157 per village.

[15] Strauch’s research in Tai Po (1983) reveals that many small villages were just residential clusters of agnates lacking formal organisations. Villagers instead maintained a sense of membership of a village community.

[16] Villagers in Hang Hau speak both Hakka and Cantonese. For the purpose of communication, all the Chinese terms in this article are transcribed in Mandarin.

[17] Handian 漢典, “麒麟” (qilin), https://www.zdic.net/hans/麒麟 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

[18] Hong Kong has experienced rapid social changes since the 1970s. As traditional ways of life were slowly disappearing, Hayes (2012: ix-xiii, 179-81) observed that, for the following decades, “traditional material culture” became the focus of research while “artefacts of daily life and work” were acquired and entered into museum collections. He argues that after the introduction of ICH, however, “traditional festivals and their associated rituals and performances” have become popular research topics, while the study of material culture became increasingly neglected. Hayes argues that ICH and material culture are in fact indivisible as they often interact with each other, and therefore should be explored and studied together.

[19] The five elements are metal, wood, water, fire, and earth.

[20] According to some elderly villagers, there was a villager in the Hang Hau District who was famous for crafting unicorn heads. It usually took him several months to finish one unicorn head.

[21] People believe there are two types of ritual pollution. One is related to giving birth (Ahern 1978) and the other is generated by death (Watson J. 1982).

[22] In the past, the unicorn troupe, equipped with a sedan chair, would go to pick up the bride from her village.

[23] Temple festivals and Jiao festivals are major communal events in rural Hong Kong. Local communities organise temple festivals to celebrate the birthdays of their patron deities. People also hire Daoist priests to hold Jiao (cosmic renewal) festivals to pacify wandering ghosts and to thank the patron deities for their blessings. During these communal events, neighbouring villages would send their unicorn, lion, or dragon dance troupes to participate and celebrate (Liu 2003: 380-2, 2022: 36-69).

[24] They would not only visit neighbouring villages in Hang Hau, but also some in distant places. The villagers remembered that, in the 1970s, they once travelled to Yuen Long, which was 60 kilometres away, given the road at that time.

[25] Sometimes, the master would try to demonstrate the skills of the unicorn troupe with a special setup for the performance. On one of the occasions that the author observed, a wooden basin, two benches and a furled banner were placed at the centre of the courtyard. The unicorn had to use these instruments to complete the performance by picking up the furled banner, opening it, and showing the name of the unicorn troupe written on the cloth banner to the spectators.

[26] According to Chinese geomantic tradition, the auspicious siting of houses is to face south (yang 陽). The placement of the seat of honour is in the east, the direction where the sun rises, or the left-hand side of the ruler or the deity (Rawski 1988: 25).

[27] In the 1960s and 1970s, several gigantic reservoirs were built in Hong Kong. An extensive rainwater collection system was built to gather rainwater territory-wide, leading to a drastic reduction of the water supply available for paddy rice farming.

[28] According to the elderly villagers, it was a common practice to hire masters from outside to teach young villagers martial arts. The master taught the basic techniques of martial arts, which were important for developing the physical strength of the players, who would still follow the essential local rules when they performed the unicorn dance.

[29] Many village communities claim that although they worship the same deity, there are specific local significances for their patron deities. Many temple communities share the same origin story that a deity image was discovered on the beach and therefore a temple was built for the deity. This story however also suggests that it was the deity who picked the villages intentionally (Liu 1999).