BOOK REVIEWS

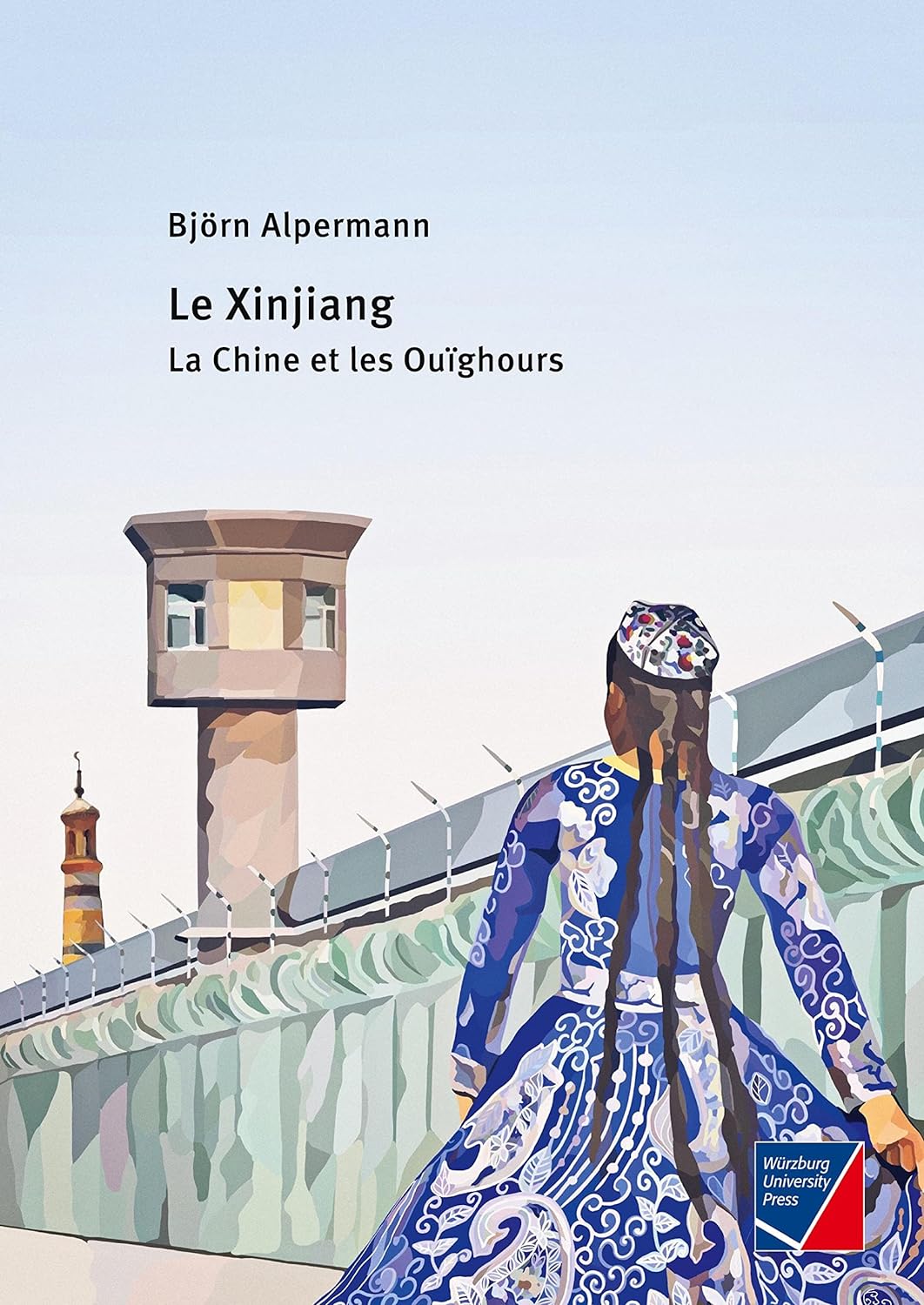

ALPERMANN, Björn. 2022. Le Xinjiang. La Chine et les Ouïghours. Würzburg: Würzburg University Press.

Sabine Trebinjac is Research Director at the CNRS and member of the Laboratory of Ethnology and Comparative Sociology, MSH Mondes, 21 allée de l’Université, 92023 Nanterre cedex, France (sabine.trebinjac@cnrs.fr).

Björn Alpermann’s book is a translation into French of a first version published in German in 2021 by the same publishing house under the title Xinjiang – China und die Uiguren. The author justifies this duplication in the preface to the French edition, noting that the crisis experienced in Xinjiang is ongoing, and that in his opinion, “there does not seem to be a study in French that examines the conflict within its historical context” (p. vii). In the general preface, Alpermann explains that his keen interest in the Xinjiang region dates from his first trip there in the mid-1990s, the second having been cancelled following the interethnic troubles of July 2009. Alpermann also states that from a scientific angle, his interest in Xinjiang and the Uyghurs forms part of his teaching of China’s policies on minorities, and he writes that “[his] analysis is based on secondary sources and not on a field study [that he himself would have] carried out” (p. IX).

Notably academic in tone, Alpermann’s introduction describes the geography of Xinjiang followed by a synthesis of its history from “ancient times,” including the Stone and Bronze ages and the Yuezhi and Xiongnu populations, followed by the “middle era” and ending with the ninth to seventeenth centuries, the period when the first individuals known as Uyghurs, huihu 回鶻, or huihe 回紇appeared. Alpermann then asks if these really were the ancestors of the Uyghurs, known today in Mandarin as 維吾爾族 weiwuerzu.

In the first section of his book, Alpermann examines the history of modern Xinjiang since the Qing dynasty, the republican years, the Mao era, and the period of reform and opening from 1978 to the 1990s. The second section is devoted to the economy and society of the twenty-first century. After presenting the main socioeconomic changes that occurred with the development of the Great Western Development Program (xibu dakaifa 西部大開發), the migration of the Han, the establishment of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (bingtuan 兵團), urbanisation, and Xi Jinping’s project for the New Silk Road, Alpermann gives us a chapter entitled “Ethnic Identity, Language, and Chinese Educational Policy” followed by another, “Ethnic Identity and Religion, Ethnic Identity and Music.” In these last two chapters, Alpermann summarises what has previously been written on the national minorities: the importance of the concept of oasis, interethnic Han/Uyghur relationships, the differentiated education of Uyghur pupils, stereotypes, the wearing of headscarves, endogamy, literature, television, religious traditions, differences in food and hygiene between Han and Uyghurs, and lastly music, both classical and popular (rock, disco, reggae, metal). In these 50 pages intended to constitute an inventory of the sociopolitical situation in Xinjiang, the author nonetheless betrays his distance from the field. The point of view of the Uyghurs, their everyday experiences, and the feelings (injustice, anger, anxiety) of the community are virtually absent, although these elements have been well documented (see particularly Smith Finley 2013; Roberts 2020; Byler 2021).

Lastly, in the third section, Alpermann devotes three chapters to the Xinjiang conflict: (1) Protests, Terrorism, Securitisation (2000-2015), (2) Repression and Cultural Genocide, (3) The International Dimension. It should be noted that neither Alpermann nor anyone else has been able to travel to Xinjiang to assess the situation close-up. Since 2016, with the nomination of Chen Quanguo 陳全國 to the post of Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in Xinjiang, followed by the setting up of the first reeducation camps in 2017, access to the region has been strictly regulated. Although witness accounts have filtered through, certain of which have been published (Sauytbay and Cavelius 2021; Haitiwaji and Rozenn 2022), Alpermann, who has read the writings of Adrian Zenz, one of the most virulent denunciators of the Chinese state’s policy in Xinjiang, does not measure up to these publications. The author indicates, for example, that “the book [by Sauytbay and Cavelius] itself is not immune to criticism since several factual errors and exaggerations are to be found within it” (p. 167). Here, one would have liked the author to have produced more than one example (note No. 24) of such errors in order to gain a greater understanding of the limits he attributes to these accounts.

In a general summary, Alpermann finally mentions the unprecedented intensity of the measures taken against Xinjiang’s minorities and the government’s wish to work towards Hanisation, concluding that, “in my opinion, we may legitimately use the term cultural genocide” (p. 189). In this respect, I cannot follow Alpermann since, as I recently wrote, “the crime of cultural genocide is not (…) recognised as such in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. However, to call this simply genocide does not seem appropriate since its definition, as recorded in Article 6 of the Rome Statute, does not correspond exactly to the acts committed by the Chinese government” (Trebinjac 2020: 200; see also Finnegan 2020).

Although not written by a specialist in the region, the book nonetheless has the merit of giving us an accurate presentation of Uyghur history. As Alpermann noted, until now a general, summarised work in French on the Uyghur question and the Xinjiang region has not existed. This manual therefore has the merit of giving a Francophone readership access to the first documented summary of existing knowledge, for the most part in English. The bibliography, excessive on certain aspects, is mainly made up of Anglophone sources. It is regrettable, then, that the publication of the French edition was not an opportunity to include and highlight French academic work on the region – since French specialists largely participated in the concert of nations standing up against the tragedy suffered by the Uyghurs and Kazakhs of Xinjiang. A dialogue with French researchers would have enabled the author to enrich his work with fresh elements on aspects as diverse as early history (the seminal work of James Russell Hamilton), sociolinguistics (with Giulia Cabras’s remarkable thesis, published in 2018), music (Trebinjac 2000a, 2000b, 2004, 2008), and geopolitics (Rémi Castets).

Translated by Elizabeth Guill.

Björn Alpermann’s book is a translation into French of a first version published in German in 2021 by the same publishing house under the title Xinjiang – China und die Uiguren. The author justifies this duplication in the preface to the French edition, noting that the crisis experienced in Xinjiang is ongoing, and that in his opinion, “there does not seem to be a study in French that examines the conflict within its historical context” (p. vii). In the general preface, Alpermann explains that his keen interest in the Xinjiang region dates from his first trip there in the mid-1990s, the second having been cancelled following the interethnic troubles of July 2009. Alpermann also states that from a scientific angle, his interest in Xinjiang and the Uyghurs forms part of his teaching of China’s policies on minorities, and he writes that “[his] analysis is based on secondary sources and not on a field study [that he himself would have] carried out” (p. IX).

Notably academic in tone, Alpermann’s introduction describes the geography of Xinjiang followed by a synthesis of its history from “ancient times,” including the Stone and Bronze ages and the Yuezhi and Xiongnu populations, followed by the “middle era” and ending with the ninth to seventeenth centuries, the period when the first individuals known as Uyghurs, huihu 回鶻, or huihe 回紇appeared. Alpermann then asks if these really were the ancestors of the Uyghurs, known today in Mandarin as 維吾爾族 weiwuerzu.

In the first section of his book, Alpermann examines the history of modern Xinjiang since the Qing dynasty, the republican years, the Mao era, and the period of reform and opening from 1978 to the 1990s. The second section is devoted to the economy and society of the twenty-first century. After presenting the main socioeconomic changes that occurred with the development of the Great Western Development Program (xibu dakaifa 西部大開發), the migration of the Han, the establishment of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (bingtuan 兵團), urbanisation, and Xi Jinping’s project for the New Silk Road, Alpermann gives us a chapter entitled “Ethnic Identity, Language, and Chinese Educational Policy” followed by another, “Ethnic Identity and Religion, Ethnic Identity and Music.” In these last two chapters, Alpermann summarises what has previously been written on the national minorities: the importance of the concept of oasis, interethnic Han/Uyghur relationships, the differentiated education of Uyghur pupils, stereotypes, the wearing of headscarves, endogamy, literature, television, religious traditions, differences in food and hygiene between Han and Uyghurs, and lastly music, both classical and popular (rock, disco, reggae, metal). In these 50 pages intended to constitute an inventory of the sociopolitical situation in Xinjiang, the author nonetheless betrays his distance from the field. The point of view of the Uyghurs, their everyday experiences, and the feelings (injustice, anger, anxiety) of the community are virtually absent, although these elements have been well documented (see particularly Smith Finley 2013; Roberts 2020; Byler 2021).

Lastly, in the third section, Alpermann devotes three chapters to the Xinjiang conflict: (1) Protests, Terrorism, Securitisation (2000-2015), (2) Repression and Cultural Genocide, (3) The International Dimension. It should be noted that neither Alpermann nor anyone else has been able to travel to Xinjiang to assess the situation close-up. Since 2016, with the nomination of Chen Quanguo 陳全國 to the post of Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in Xinjiang, followed by the setting up of the first reeducation camps in 2017, access to the region has been strictly regulated. Although witness accounts have filtered through, certain of which have been published (Sauytbay and Cavelius 2021; Haitiwaji and Rozenn 2022), Alpermann, who has read the writings of Adrian Zenz, one of the most virulent denunciators of the Chinese state’s policy in Xinjiang, does not measure up to these publications. The author indicates, for example, that “the book [by Sauytbay and Cavelius] itself is not immune to criticism since several factual errors and exaggerations are to be found within it” (p. 167). Here, one would have liked the author to have produced more than one example (note No. 24) of such errors in order to gain a greater understanding of the limits he attributes to these accounts.

In a general summary, Alpermann finally mentions the unprecedented intensity of the measures taken against Xinjiang’s minorities and the government’s wish to work towards Hanisation, concluding that, “in my opinion, we may legitimately use the term cultural genocide” (p. 189). In this respect, I cannot follow Alpermann since, as I recently wrote, “the crime of cultural genocide is not (…) recognised as such in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. However, to call this simply genocide does not seem appropriate since its definition, as recorded in Article 6 of the Rome Statute, does not correspond exactly to the acts committed by the Chinese government” (Trebinjac 2020: 200; see also Finnegan 2020).

Although not written by a specialist in the region, the book nonetheless has the merit of giving us an accurate presentation of Uyghur history. As Alpermann noted, until now a general, summarised work in French on the Uyghur question and the Xinjiang region has not existed. This manual therefore has the merit of giving a Francophone readership access to the first documented summary of existing knowledge, for the most part in English. The bibliography, excessive on certain aspects, is mainly made up of Anglophone sources. It is regrettable, then, that the publication of the French edition was not an opportunity to include and highlight French academic work on the region – since French specialists largely participated in the concert of nations standing up against the tragedy suffered by the Uyghurs and Kazakhs of Xinjiang. A dialogue with French researchers would have enabled the author to enrich his work with fresh elements on aspects as diverse as early history (the seminal work of James Russell Hamilton), sociolinguistics (with Giulia Cabras’s remarkable thesis, published in 2018), music (Trebinjac 2000a, 2000b, 2004, 2008), and geopolitics (Rémi Castets).

Translated by Elizabeth Guill.