BOOK REVIEWS

Border as Dispositif: Sovereignty, Discipline, and Governmentality at the China-Kazakhstan Border

Xuan Zhao is Associate Professor in the School of Sociology and Anthropology at Sun Yat-sen University, No. 135 Xingang Xi Road, Haizhu District, Guangzhou, China (zhaoxuan5@mail.sysu.edu.cn).

Introduction

In the 1990s, the field of border studies experienced a pivotal shift (Zhao and Liu 2019; Zhurzhenko 2023). The contemporary paradigm, characterised by a “process turn” and a “practice turn,” thus moves beyond static sovereign borders that focus on geopolitics to dynamic multi-borders that focus on biopolitics (Brambilla, Laine, and Bocchi 2016; Paasi 2022). This new paradigm has prompted dual shifts, respectively, toward the everyday interactions of diverse actors, and toward understanding the complex, multifaceted nature of power relations at borders (Paasi 2012; Gilles et al. 2013; Jones and Johnson 2016; Pfoser 2020; Newman 2023). The new paradigm leads to the mushrooming of empirical studies focusing on multi-actor interactions that shape borderscapes – dynamic and fluid spaces where material, social, and cultural processes interact – and distinct border subjectivities, or on the identities and experiences shaped by the unique power relations, negotiations, and lived realities in border regions (Parker and Vaughan-Williams 2012; Mezzadra and Neilson 2013).

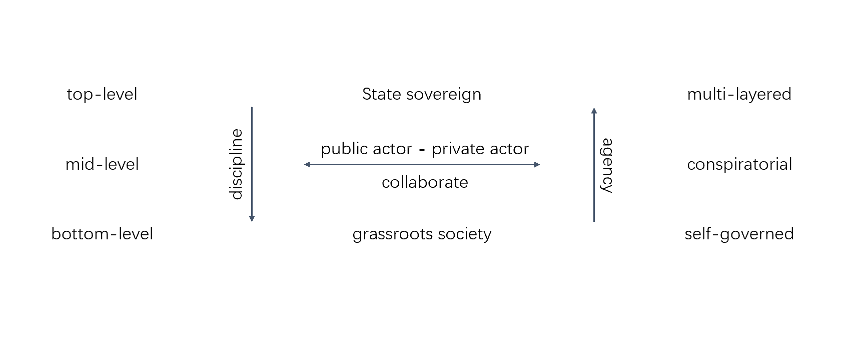

As the result of the dual shifts since the 1990s, multiple analytical frameworks have been adopted to investigate the daily practices through which multiple actors construct, experience, and contest the borders, and the newly emerged subjectivities and agencies (Andersen, Klatt, and Sandberg 2016; Brambilla and Jones 2020; Dean K. 2020). Concepts such as governmentality, biopolitics, and assemblage, all Foucauldian terms that provide a powerful framework for analysing how power, governance, surveillance, and subject formation are enacted and contested, are frequently employed in contemporary border studies (Sparke 2006; Walter 2006; Dean K. 2020). To synthesise the theoretical advances in this line of literature, this study develops an analytical framework inspired by dispositif, also a Foucauldian concept, which refers to a complex and adaptable network of discourses, institutions, and practices that work together to exert control and influence behaviours, identities, and power relations within society (Bussolini 2010). Through the lens of the border as dispositif, this study interprets the border, in this case the Khorgas port between China and Kazakhstan, as a space of interaction among multilayered sovereign power shaped by top-down strategic arrangements, conspiratorial disciplines tacitly enacted by local traders and border regulators, and resilient self-governance that finds room through resistance against, and collaboration with, the government.

Drawing on five comprehensive field surveys conducted at Khorgas, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, this research explores how the border, conceptualised as dispositif, generates three distinct types of borderscapes (sovereignty, discipline, and governmentality), and examines their effects on subject formation and agency, which in return reshape power relations at the border (Wichum 2013). This research develops a three-level analytical framework to address sovereignty, discipline, and governmentality as interconnected layers of power that shape border spaces. The article is structured into four sections. The first one introduces the analytic framework, highlighting its three components: sovereignty, discipline, and governmentality. The second section elaborates on the rationale for selecting Khorgas as a case study and outlines the methods. The third section analyses the interplay of power dynamics. The final section discusses the contribution of the dispositif approach and suggests potential avenues for future research.

Literature review

The dispositif-inspired analytical framework

Dispositif, a concept originally developed in Foucault’s early work on body control and “knowledge-power” dynamics, evolved and was expanded in his analyses of population regulations and governmentality (Legg 2011; Elden 2022). As its focus shifted from identifying and correcting deviant subjects to creating normative standards based on statistical averages, this term became an adaptable framework composed of various components including discourses, institutions, laws, architectures, regulatory decisions, and administrative measures, tailored to meet immediate social needs (Delanda 2019). Therefore, this shift has prompted many societal systems, considered as dispositifs, to move away from rigid, centralised control to operate in a more flexible, decentralised manner, allowing for a more dynamic and responsive management of the circulation of objects, information, and people in the modern era. By adapting to changing conditions and addressing perceived threats effectively, these dispositifs become better equipped to maintain order (Foucault 2009, 2018).

Both real-life settings, such as hospitals, schools, and prisons, and abstract settings, including security (Wichum 2013), algorithms (Panagia 2020), citizenship (Merryman 2021), and personhood (Esposito 2012), can be conceptualised as various dispositifs, serving as nodes where elements converge to form a governance rationale (Callewaert 2017). By shaping actors and generating differentiated subjective effects, this rationale causes continuous interactions between these components and constant adjustments and recalibrations on dispositifs in return. Moreover, this study proposes that the concept of technologies of the self, which highlights how individuals or groups use their agency to either conform to, or resist, the norms established by the existing power relations, be incorporated into the dispositif-inspired analytical framework as a source of ambiguities with the potential for disorder, to further complicate and enrich this concept of dispositif.

Inspired by the concept of dispositif, a tool to operate on both the micro-body and macro-population, this research aims to develop a three-level analytical framework for border studies. At the top level, sovereignty represents the foundation of control, rooted in politico-legal frameworks that assert dominance and maintain order over a particular territory (Frost 2019). Sovereignty, as the overarching power structure, can shape conditions under which other forms of power function. At the mid-level, discipline emerges as a mechanism through which sovereignty is enforced, drawing on knowledge to regulate behaviours and optimise productivity (Stankiewicz and Ostrowicka 2020). Discipline operates through corrective measures that enhance both the efficiency and conformity of other actors, especially subjects, within the power framework. At the bottom tier, governmentality functions as the most diffuse and indirect form of control, which operates subtly through dispositifs by using laws and regulations to direct human behaviour, manage economic activities, and influence social dynamics (Dillon 2007; Esmark and Triantafillou 2009; Braun 2014). This indirect control encourages self-regulation at the grassroots level while remaining adaptive and productive. In this analytical framework, dispositifs allow different subjects to leverage their autonomy and agency to navigate between different forms of power within the structures of governance (Jones 2012).

The complex interplay between control and autonomy makes dispositif a powerful yet adaptable tool in the landscape of governance. Although Foucault developed several theoretically interrelated concepts (apparatus, assemblage, and governmentality) to capture the state-society relationship, dispositif is best suited for analysing governance in complex, transnational contexts, where power operates through both formal controls and everyday interactions between actors, including non-state ones. Considered interchangeable with apparatus, focusing on structured systems of control (Agamben 2009), dispositif captures a broader array of governance elements, including informal mechanisms, local practices, and evolving geopolitical forces. Unlike governmentality, focusing on state rationalities and techniques for managing populations (Dean M. 2009), dispositif emphasises the fluid, multilayered nature of power, incorporating discourses, institutions, and material practices (Rabinow and Rose 2003) to allow for a more flexible analysis of governance, especially in situations where power is dispersed across formal and informal sites (Ong 2006). Lastly, while both dispositif and the assemblage approach stress the complexity of governance, dispositif focuses more on the strategic power deployment, whereas assemblage emphasises the spontaneous and emergent configurations of governance (Deleuze and Guattari 1987; Deleuze 1992). Therefore, as dispositif captures the intentional, relational aspects of power, it is better suited for contexts such as a border where governance continuously adapts to changing conditions.

Border as dispositif

The concept of dispositif offers a profound resonance within the field of border studies. The everyday activities at a border, which entail interactions among multiple actors, such as border regulators, cross-border traders, and border residents, as well as borderscapes, exhibit the multifaceted nature of dispositif in action (Krichker 2021; Mohanty 2023). Due to its critical potential, this concept has gained significant traction in critical border studies, shedding light on complex dynamics at multiple geopolitical junctures (Sohn 2016). Daniel Fischer’s ethnographic study of Spain’s SIVE (Sistema Integrado de Vigilancia Exterior, Integrated exterior surveillance system) adopts a dispositif framework to uncover complex enforcement mechanisms and their wide-reaching social impacts (2018). Likewise, Alison Mountz applies this term to the Mediterranean context (2020), highlighting how European countries’ extension of maritime borders to intercept migrants evades the humanitarian duties and strips individuals of their rights by reducing them to “bare life” – stateless without legal protection. At the Israeli-Palestinian border, research about checkpoints shows how disciplinary practices transform Palestinians into a compliant workforce while paradoxically creating a “checkpoint economy” that spurs new social interactions and forms of resistance against border management (Griffiths and Repo 2018).

Although the concept of dispositif is widely adopted, many existing studies focus on just one or two levels of analysis, either sovereignty, discipline, or governmentality, when examining border dynamics, and miss the full complexity of borders as multilayered phenomena. A more comprehensive analytical framework, addressing all three levels, allows researchers to capture the interconnectedness of these dimensions and offers a fuller understanding of borders as fluid spaces of power. This approach moves beyond the traditional binary logic of “state domination” or “local knowledge” often found in previous studies (Geertz 1985; Painter 2006), encouraging a deeper explanation of how borders are not merely physical barriers but also sites of governance and subject formation. By considering the interplay between state control, social practices, and subjectivity, this framework illuminates borders as spaces where power is continuously negotiated and refined. It further enhances the analysis of border control and its social impacts, offering valuable insights for more human-centred and effective border management strategies that address the diverse needs and rights of affected populations (Nieswand 2018). This enriched perspective advances both theoretical and practical approaches to border governance.

Xinjiang’s border as dispositif

China’s borderlands have transitioned from remote, underdeveloped territories to pivotal hubs of geopolitical, economic, social, and cultural significance, mirroring the nation’s growing global stature (Oliveira et al. 2020; Karrar 2022). Positioned at the intersections of multiple countries, these regions act as vibrant conduits for the flow of people, goods, and ideas, which catalyse economic integration and cultural exchanges (Dean, Sarma, and Rippa 2022). Enhanced by substantial infrastructural upgrades, such as the development of roads and railways, connectivity with neighbouring countries has been significantly improved, which stimulates local economies and consolidates geopolitical relationships (Mayer and Zhang 2021). These strategic investments reflect China’s ambitions to influence global trade routes and promote regional stability within these dynamic border areas (Winter 2020). Through these initiatives, China successfully develops new politico-institutional structures to regulate and solidify the border regions, and connects its neighbours’ ambitions of development with China’s geopolitical pursuits, at least partly driven by anxieties over cross-border ethnic minorities that have been reoriented inwards (Murton, Lord, and Beazley 2016; Murton 2017a and b). China’s initiatives often come with a cost, leading to environmental degradation and other undesirable outcomes (Sarma, Faxon, and Robert 2022; Sarma, Rippa, and Dean 2023; Murton and Narins 2024).

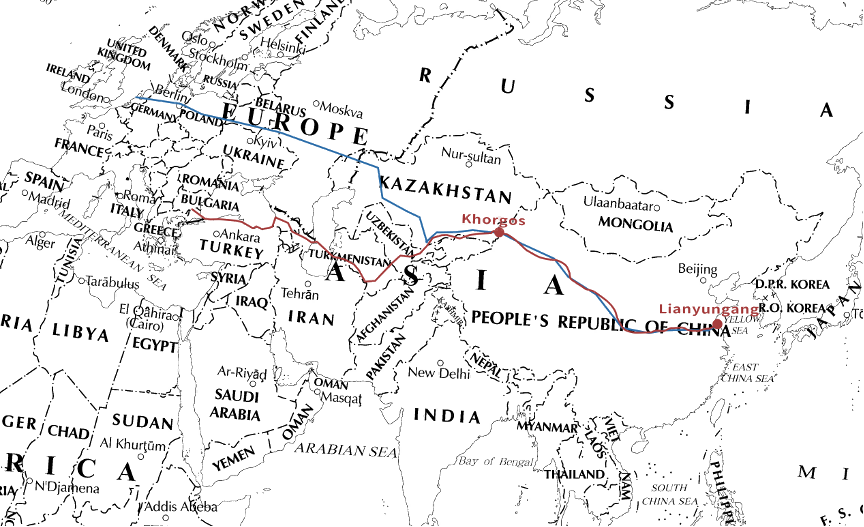

The Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region is notably prominent among China’s strategic borderlands, playing a vital role in the Belt and Road Initiative through establishing economic corridors that project Chinese influence deep into Europe and the Middle East (Rippa 2019; Tang and Joldybayeva 2023). Xinjiang’s wealth of natural resources and strategic position as an energy conduit markedly enhance its geopolitical importance. However, the region’s complex sociopolitical fabric, marked by a diverse ethnic population and deep-seated cultural connections with neighbouring Central Asian nations, introduces multifaceted challenges and opportunities in governance and policy implementation (Grant 2020; Tsakhirmaa 2022; Alff, Konysbayev, and Salmyrzauly 2023). This complexity underscores Xinjiang’s status as a crucial economic zone and elevates its value as a key site of China’s security and diplomatic strategies (Pötzsch 2015; Ngo and Hung 2019, 2024). China’s mix of economic initiatives with security measures is a delicate balancing act, aiming to stabilise and develop the region while managing ethnic dynamics (Alff and Spies 2023). Consequently, Xinjiang serves as both a gateway and a guardhouse, which facilitates China’s geopolitical ambitions through critical trade routes while at the same time acting as a fortified region where state power is exercised to maintain security, manage cross-border interactions, and control local populations.

This research applies a dispositif-inspired analytical framework to examine the dynamics of Xinjiang’s borders, specifically focusing on Khorgas. At the top level, the study finds that state sovereignty is unevenly distributed across both actual and internal borders, with authority multiplied as varied duties are spatially allocated among the three national gates, and asymmetrically asserted by the two nations involved. At the mid-level, while disciplinary power is exerted from above, local public actors, who lack the capacity to enforce sovereign authority effectively, collaborate with private actors for a range of purposes, such as with Camel Teams (luotuo dui 駱駝隊) – informal groups engaged in commodity transportation by leveraging the price difference between commodity inside and outside the duty-free zone. At the grassroots level, society retains a significant degree of autonomy and agency, adapting to state regulations that attempt to subtly control their activities, and fosters a largely self-sustaining market economy. This framework explores the sovereign practices that facilitate and prohibit the cross-border movement of people and goods, crucial for regional economic development. Moreover, this framework sheds light on the agency of marginalised subjects with low socioeconomic status and analyses how they manage to navigate state governance through their everyday interactions at the border. This nuanced exploration deepens our understanding of the sophisticated interplay of forces shaping Xinjiang’s borders and challenges traditional perceptions of national boundaries. By analysing diverse actors at multiple dimensions, this framework marks a significant theoretical and empirical advance in border studies. This approach offers critical insights into the interactions between state policies and the lived experiences of those at the margins, emphasising the active role of borders in shaping economic, social, and cultural realities (Rippa 2020, 2023).

Figure 1. The dispositif-inspired analytical framework for the Khorgas border

Credit: the author.

Research methods

Site selection

Khorgas, positioned at the western end of the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture (Xinjiang) and bordering Kazakhstan, has been a critical node for cross-border migration and trade since the Qing dynasty, partly due to its warm and temperate valley climate, which is rarely found in this region. Over the last four decades, several significant initiatives, such as the border-opening policy (1992), the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (2001), the Belt and Road Initiative (2013), as well as other strategies, have transformed Khorgas. The creation of the China-Kazakhstan Khorgas International Border Cooperation Centre (Zhong Ha Huo’erguosi guoji bianjing hezuo zhongxin 中哈霍爾果斯國際邊境合作中心, hereafter the Centre) in 2012 further enhanced the strategic importance of Khorgas as a key gateway for China’s global engagement. In October 2023, the State Council unveiled the China (Xinjiang) Pilot Free Trade Zone (Zhongguo (Xinjiang) ziyou maoyi shiyan qu 中國(新疆)自由貿易試驗區), including a tariff-free zone designated in Khorgas, reinforcing its role in China’s global economic strategy. Additionally, these developments have enhanced the logistics, trade, and infrastructure facilities in Khorgas, boosting its capacity as a major economic hub.

Figure 2. The geopolitical and geoeconomic position of Khorgas Port in China’s Belt and Road Initiative

Credit: base map sourced from China’s Ministry of Natural Resources and adapted by the author.

Note: the new Asia-Europe land-sea transport channel (Xin Ya Ou luhai lianyun tongdao 新亞歐陸海聯運通道) starts from Lianyungang (China) in the east and connects Eurasia through Khorgas. In the figure, the red line represents the China-Türkiye (trans-Caspian Sea) route, and the blue line represents the China-Europe route.

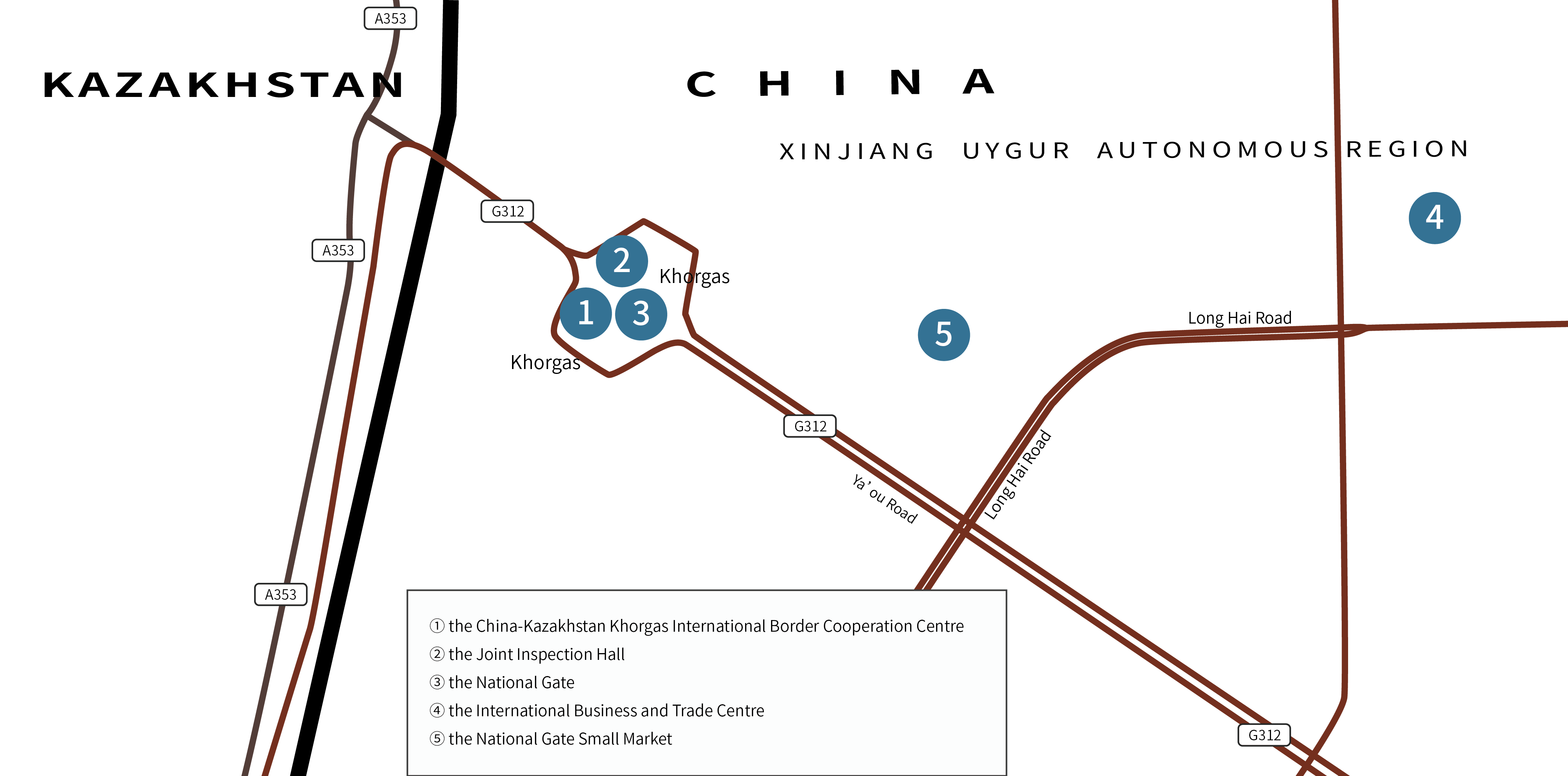

Thus, the economic landscape of Khorgas has been materially redefined through investments from various public and private actors. This influx of capital has brought a variety of changes to the architectural and functional aspects of the port region. Key developments such as the construction of the joint inspection hall (2011), the refurbishment of the old border trade market (2007), the initial establishment and subsequent evolution of the Centre (2012) and the National Gate Small Market (Guomen xiao shichang 國門小市場, 2016) show the evolution of Khorgas’s physical and economic fabric. These transformations are both physical and symbolic, reflecting how multiple layers of power and governance interact and reshape spaces to meet both local and broader geopolitical needs at the border.

Each of these spaces serves a distinct purpose at different times, adapting to the changing requirements of trade, security, and diplomatic relations between China and Kazakhstan. For example, the joint inspection hall, facilitating efficient border controls and customs procedures, symbolises the sovereign aspect of the border, asserting state control and regulatory mechanisms over cross-border movements. On the other hand, places such as the Centre highlight the economic pursuits of trade and commerce, which promote local economic development and China’s broader strategic goals. Meanwhile, as detailed later on in this paper, smaller, more localised markets such as the National Gate Small Market have often catered to the everyday needs of local and cross-border residents, illustrating the micro-level impacts of macro-level policies.

Figure 3. Local map of Khorgas Port on the China-Kazakhstan border

Credit: the author, based on observations of Google Maps and Baidu Maps.

These developments showcase the variability of power relations among a diverse set of stakeholders, including state authorities, local government officials, entrepreneurs, cross-border businesspersons, regular customers, and even marginalised local residents. Each stakeholder group interacts within these spaces under the overarching structures of sovereignty, discipline, and governmentality, influencing and being influenced by the constant evolution of the region. Through these interactions, Khorgas has emerged as a perfect example of how border regions are shaped and reshaped by domestic policies and international relations.

Data collection

This ongoing study on the dynamics of mobility and control at Khorgas Port employs an approach that combines participant observation, in-depth interviews, and autoethnography to offer a comprehensive understanding of this urban border environment through the lens of the analytical framework inspired by dispositif (Megoran 2006). The research team, composed of three master students led by a faculty member (the author), conducted five rounds of fieldwork at Khorgas Port between December 2016 and January 2017, April and July 2017, August 2018, July and October 2019, and July and August 2024. During the Covid-19 pandemic, these efforts were complemented by online interviews. The team aimed to monitor and document the continuous developmental changes at the port, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the evolving dynamics and infrastructure over time. These multiple phases of data collection enabled the researchers to capture both immediate shifts and longer-term trends in the region’s development.

The members of the research team conducted intensive fieldwork at key border spaces, including the Centre and the National Gate Small Market, using participant observation to deeply engage with the border dynamics of mobility and control. By embedding ourselves in these settings, we were able to document daily practices and interactions in real time, gaining insights into how individuals and groups navigate state and local policies. The firsthand observation of the negotiations between traders, border agents, and other actors allowed us to capture the subtle ways policies were adapted or circumvented. We were thus able to document both the challenges they face, and the adaptive strategies adopted to mitigate state-imposed constraints. In essence, this method provided rich, grounded data on how border policies influence everyday life.

To enhance our observational data, we conducted a series of in-depth interviews with 21 diverse stakeholders, such as port management staff, local grassroots cadres, traders, members of Camel Teams, and restaurant owners (see Table). We compiled these insights into a collection of oral histories titled The realm of the common people: Oral accounts of people at the borderland crossings in northwest China (Zhao and Wu 2020). These narratives offer a rich, nuanced understanding of the everyday lives of border residents. By capturing personal perspectives, the oral histories reveal the broader socioeconomic impacts of border governance on these communities, and offer a valuable context for the intersection between policy and lived experience at the border. Furthermore, these in-depth interviews were supplemented by numerous unstructured, informal talks with other locals, all documented in our field notes.

Table. Biographical information on interviewees

| Name | Occupation |

| WSQ | Female, 67 years old. Owner of a stall in the National Gate Small Market. |

| YYC | Male, 81 years old. Owner of a stall in the National Gate Small Market. |

| GYX | Male, 77 years old. Owner of a gift shop within the Centre. |

| TFQ | Female, about 70 years old. Owner of a gift shop within the Centre. |

| LQ | Female, about 50 years old. Owner of a gift shop within the Centre. |

| WK | Male, 32 years old. Owner of a Kazakhstan specialty store within the Centre. |

| LLJ | Male, 48 years old. Owner of a gift shop within the Centre. |

| FJ | Female, about 45 years old. Owner of a shop within the Centre, also doing cross-border e-commerce. |

| ZHF | Male, about 55 years old. Hotel owner with extensive experience in border trade. |

| BLM | Female, 39 years old. Hotel receptionist, also shopping guide at the Centre. |

| LQF | Male, 29 years old. Staff member of the Centre’s Management Committee. |

| MSJ | Male, 38 years old. Staff member of the Centre’s Management Committee. |

| YCH | Female, 78 years old. Farm labourer and Khorgas resident. |

| XZZ | Male, about 40 years old. Staff member at the Khorgas Entry-exit Border Checkpoint. |

| AYG | Male, 28 years old. Staff member of the Propaganda Department, Khorgas Municipal Party Committee. |

| XMJ | Female, about 30 years old. Member of a Camel Team and waitress in a gift shop within the Centre. |

| TAY | Female, about 65 years old. Member of a Camel Team and nanny. |

| LC | Male, about 55 years old. Head of a Camel Team. |

| YDS | Male, about 60 years old. Head of a Camel Team. |

| DZ | Male, about 50 years old. Employee of the 62nd Unit, Xinjiang Development and Construction Corps (Xinjiang shengchan jianshe bingtuan 新疆生產建設兵團), also running a reclamation depot. |

| LG | Male, 66 years old. Retired worker of the 62nd Unit, Xinjiang Development and Construction Corps. |

Given Khorgas’s stringent border management, which cannot be fully captured by observation and interviews alone, we decided to incorporate autoethnography into our research methodology, and proactively approached traders and members of Camel Teams. After establishing a degree of mutual trust, we persuaded them to recruit some members of our research team, including myself. Subsequently, we took on their roles, acting as trader assistants or new members of Camel Teams, and walked through the cross-border trade processes in their shoes. We acted as customers and recruited members of the Camel Teams to purchase products on our behalf, which created opportunities to engage them in in-depth conversations. This approach allowed us to build trust and gather insights into their experiences and the challenges they face in navigating cross-border trade. By immersing ourselves in these roles, we could personally experience the lived realities of border governance and its impacts on the social dynamics of the border community, gaining critical insights in the process.

Together, these complementary methods provide a rich, multidimensional view of the borderscapes at Khorgas Port, which reveals the complex interplay of sovereignties, disciplines, and subjectivities. The approach adopted captures both the macro-level operations of border governance and the micro-level experiences of those who live and work at the border, providing valuable insights into the practical implications of border management strategies.

The multilayered sovereignties in the China-Kazakhstan border

Border management, a sovereign practice, traditionally involves rigorous screening of individuals and goods to ensure security and operational efficiency jointly by two states (Salter 2008). This practice inherently creates a power dynamic where normal legal rights may be temporarily suspended by sovereign power. However, given the strategic importance of the China-Kazakhstan border within China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the asymmetry of economic development, Kazakhstan’s intermediary position between China and Russia in the post-Soviet era, complex cross-border ties between Kazakhstan and Kazakhs in China, and potential geopolitical crises stemming from regime-changed Afghanistan, the sovereign practices in Khorgas unveil a more complex scenario. While two sovereignties coexist, China’s influence predominates, and determines border policies, economic development, and security measures, in many cases unilaterally, with Kazakhstan’s sovereignty playing a more reactive or accommodating role. In addition, at Khorgas, China has opted to retreat from the immediate border and erect an internal border one kilometre within its own territory to create borderless space for trade and business (unlike the US-Mexico border where Mexico, the weaker side, often yields to pressure from the stronger one). From the perspective of this analytical framework, such practices, undertaken by the Chinese central government, constitute a dispositif of multilayered sovereignties at the top level.

The state of multilayered sovereignties in Khorgas is tangibly manifested through the distinct functions assigned to three national gates. The Old Gate (Laoguomen 老國門), established before 1990 and located a kilometre away from the actual border, functions as a border outpost staffed by guards, serving to monitor and protect the internal territory from this secondary boundary located on the Chinese soil. In contrast, the New Gate (Xinguomen 新國門), inaugurated in 1997 and positioned at the actual border, symbolises China’s territorial integrity, although it has since become a scenic site for tourism and business, over which China exercises only nominal sovereign control. Ten kilometres south along the border lies the South Gate (Nanguomen 南國門), constructed to redirect the flow of goods and people from the New Gate. Currently serving as the main entry point into China, this gate focuses on promoting cross-border trade and exchanges, while China retains control over screening people and goods for security and other regulatory purposes at checkpoints such as the Old Gate along the internal border. Together, these three gates create a scenario in which China’s sovereignty is unevenly distributed, with each gate assigned distinct functions that create a layered structure between the internal and actual borders. Hence, China’s sovereignty is extended and multiplied, impacting those affected by this unique arrangement. More importantly, a port official affirmed that this spatial arrangement had been widely adopted at other Xinjiang border ports, such as Ulash-Tai, Takashken, Jeminay, Baketu, Alashankou, and Dulata. This multiplication of sovereignties caused by the functional division of the gates further reflects Khorgas’ socioeconomic change, which has brought into use previously underdeveloped areas limited by the natural environment, and consolidates sovereign control over the border region. A senior port official explained:

When people refer to a place as a “restricted zone,” they aren’t just talking about areas that are legally off-limits. They also mean those undeveloped desert regions that, while not explicitly prohibited, effectively deter people from entering. People often ask, “Why bother going there?” (Interview with WSQ, 30 April 2017)

At the core of the central practices at Khorgas Port is the unique International Border Cooperation Centre, established in 2012 as a key part of a bilateral agreement during President Nazarbayev’s 2004 visit to Ili Prefecture, an endeavour that could be exclusively undertaken by sovereign nations. This agreement was once seen as embracing the concept of a “borderless world,” a notion initially celebrated in Europe and later adopted globally at the turn of the millennium. Originating from the 1990s scholarly proposals by figures such as James A. Chamberlain (2021), this idea advocates the unrestricted movement of individuals across borders and the tax-free passage of goods. Embodying this concept, the Centre includes a national gateway that provides unrestricted access, enhancing its appeal as a significant tourist site. Passport holders enjoy free entry, while those without passports can obtain a transit permit at the Khorgas Administrative Service Centre, located around one kilometre away from the Centre. The fee is RMB 20 for a single-pass permit or RMB 180 for an annual pass, making it accessible for frequent travellers and enhancing cross-border exchanges. This setup therefore boosts both tourism and the local economy by encouraging regular visits and trade. However, such apparent borderless space at the actual border cannot be created without the reassertion of China’s sovereignty at the internal border, consisting of joint inspection halls that function like traditional border checkpoints.

Besides being spatially multilayered between the actual and secondary borders, China’s sovereignty is also procedurally multilayered at Khorgas. My field investigation finds that, at the inspection halls where customs, inspections, and quarantine procedures take place, China’s sovereignty is embodied to a fuller extent, and visitors experience a loss of privacy as they are subjected to more intense scrutiny. The interactions between state sovereign power and individual freedom render visitors “exposed,” transforming their presence into one of complete transparency where every action and detail faces stringent regulations that are rigorously enforced to ensure security. The use of photography and mobile phones is generally prohibited to maintain privacy and control over the dissemination of sensitive information. In addition, all individuals are required to undergo thorough security screening, which includes X-ray scans of any carried items, body scans through hand-held metal detectors, and detailed checks of passports or permits by the inspectors. For first-time visitors, the inspectors usually check their passports for visa records from other countries, a practice not exercised in the Centre. The security sometimes extends to questioning and the monitoring of conversations, with occasional checks of personal digital content such as instant messages. The discretionary power of intensive scrutiny wielded by the inspectors with considerable latitude in deciding the scope and intensity of inspections stems from sovereign authority, which is inherently arbitrary and extends beyond formal rules. While these measures aim to uphold safety standards and protect border integrity, they reflect the absolute and non-negotiable nature of state sovereignty. Consequently, individuals participating in cross-border activities often find themselves in a passive role, forced to comply with the authority and protocols dictated by the state. This underscores the intrusive reach and enduring presence of state sovereignty in such controlled environments.

Although multilayered and unevenly distributed, sovereignties between the actual and internal borders are in constant tension and thus unstable. Naturally, the weaker side is likely to be enhanced through the interactions with the stronger one. At Khorgas Port, despite the initial intention to transform the actual border at the Centre into a free-entry-and-exit zone, increased scrutiny at the internal border has led to more formalised rules at the Centre. This shift underlies a tightening of controls that contrasts sharply with the original goals. During a field trip in April 2017, we found individuals from Kazakhstan subjected to metal detector tests and security checks akin to those at airports, although cars from Kazakhstan were not required to be inspected. After a few months, border police stationed at more sophisticated inspection facilities could conduct vehicle checks regularly (Zhao 2018; Zhao and Liu 2018). Despite the intensification of security measures, the process at the Centre remains less intensive compared to the one at the nearest inspection hall.

While China has intensified its border controls at Khorgas, Kazakhstan has taken a more relaxed approach. Initially, Kazakhstan conducted sporadic vehicle inspections as part of its border management practices. However, as Kazakhstan’s trade dependence on China grew, along with increased spending by Chinese customers and tourists, these inspections were later discontinued. This easing of border control reflects a calculated sovereign decision by Kazakhstan, encouraged by China’s willingness to shoulder more responsibilities for border security and assert its sovereignty through heightened control and oversight. In exchange, China offers economic incentives and trade benefits, which have enticed Kazakhstan to ease its sovereign border practices. This arrangement also allows Kazakhstan to maintain the flexibility to reinstate controls when needed, all while benefitting from China’s increased role in ensuring the security and regulation of cross-border interactions.

The conspiratorial disciplines between grassroots officials and traders

Both enhanced and relaxed border controls are seen as forms of discipline imposed by sovereign power on ordinary people in the border areas. In the case of enhanced control, strict surveillance, thorough inspections, and restrictions on movement serve as direct mechanisms of control, which reinforce the absolute sovereign power by managing who and what can cross the border. On the other hand, relaxed border control, while granting more freedom, is also a form of discipline. The central state eases restrictions and encourages cross-border trade and mobility strategically to subtly direct behaviour and economic activities in alignment with state interests. In both cases, the central state exercises power to discipline ordinary people by shaping their behaviour, movements, and interactions to serve the broader goals of state governance (Liu B. 2018; Liu X. 2018; Wu 2021).[1]

However, while appearing powerful, the central state is not omnipotent in shifting easily between stringent regulation and strategic leniency, as doing so risks undermining its legitimacy and the delicate balance of power at the border, where the central state must navigate external factors such as economic pressures, geopolitical tensions, and social dynamics with extreme caution. Also, the formal authority of the central state might not always align with local needs or might not directly serve the broader interests of the sovereign itself. Therefore, the local enforcers often seek collaboration with external, usually, private, actors to achieve their objectives in a way that does not violate their own established rules. This uncomfortable collaboration often encompasses a wide range of activities from security measures to economic initiatives, which, while remaining within acceptable limits, oftentimes push the boundaries of traditional sovereignty practices.

A similar “conspiracy” also pervades the China-Kazakhstan border, particularly within the Khorgas Centre. Although the Centre’s primary goal is to enhance the cross-border flow of people and goods, complemented by duty-free shopping benefits to attract customers from both countries, the stringent flow-control measures imposed at both primary and secondary borders significantly curb its economic potential. The failure to realise other planned economic activities such as accommodation, entertainment, and tourism has led to consumption becoming the principal economic driver. However, this consumption is also heavily constrained by anti-trafficking measures that limit purchase quantities. Since Kazakh visitors typically buy inexpensive items such as shoes, hats, clothes, and small home appliances, the consumption growth relies largely on Chinese tourists who are interested in unique products not readily available in Mainland China, such as Central Asian food and high-value products such as cosmetics, cigarettes, and brand-name bags. As the duty-free policy introduces strict customs regulations on the quantity of these high-value items (each visitor is limited to two cartons of cigarettes and one bottle of alcoholic beverage), with penalties for exceeding these limits, an informal and fluid buying agency known as the Camel Teams has emerged to navigate these restrictions (Zhao 2022). Serving as intermediaries, Camel Teams help customers maximise their purchases within the confines of the regulations by subtly colluding with the Centre’s sovereign authority in managing cross-border trade.

Over the seven-year fieldwork, we found that the operation of the Camel Teams was no secret. These teams function with flexibility, lacking fixed personnel or predefined shipping schedules, and take form as needed based on the daily volume of deliveries. When orders exceed duty-free limits, business owners contact “Camel heads” (tuotou 駝頭) or “shippers,” who mobilise their teams and calculate shipping fees according to the number of trips and items to be transported. The goods they carry fall into two categories: “large items,” primarily food, and “small items,” consisting of high-value consumer products. For larger, less valuable goods, team members carry heavier loads, while high-value items are transported in smaller, lighter quantities to comply with strict customs regulations. Each item is distributed among team members, with customer contact details recorded. The team then transports the items from the Centre to a nearby square outside the duty-free zone, where they hand over the goods directly to customers, charging RMB 5 to 10 per transaction for their delivery services.

During the field trips conducted in 2017, 2019, and 2024, I approached the Camel Teams and gained a gradual understanding of their structures and behavioural patterns within the broader context of cross-border trade. On the surface, these Camel Teams appear to operate without a formal organisational structure. As locals say, “anyone can join the Camel Team.” However, these teams are built on the local social network, which consists almost exclusively of locals, or “familiar faces.” When opportunities arise, they are distributed among different team members based on the level of trust they have with the Camel head. A local female and part-time camel explains why she does this job:

I saw many people doing this job, the Centre is near my place anyway, I got bored with housekeeping and babysitting, so I came here to join them. I can make money in my spare time, the job is not tedious, with no housework in mind or anything bad. (Interview with XMJ, 15 September 2019)

A couple who also leveraged their familial ties to join this trade said:

We used to run a trash collection station in Karamay and sold it to someone else in 2016 due to the hardships involved. We stayed jobless for a while when we came back to Khorgas, with no ideal job in sight. I heard of a job opening in the Camel Teams in March 2017 from a relative and decided to give it a try. From then on, I’ve been driving to the Centre to pick things up and make some money. Oftentimes, [we are so busy that] we even skip lunches. (Interview with DZ, 30 June 2017)

All these actions, navigating the grey areas of customs regulations, are conducted under the close watch of Centre officials, the grassroots agents of sovereign power. Since these agents are multi-tasked and unable to enforce disciplinary power every time they run into a suspicious camel transaction, they tacitly conspire with them, unless the camels cross the line, such as by transporting items too large or too expensive. Usually, those carrying large items gather at the exits of the inspection halls at 4 p.m. to await customs clearance. During this waiting period, security guards are deployed to maintain order. The inspection halls feature two entry channels: the tourist passage, generally kept open, and the emergency passage, usually closed. However, during peak tourist seasons, or when large items need to be moved, the inspection halls will open the emergency passage to facilitate efficient delivery by Camel Teams, thus minimising disruption to regular shoppers and preserving the quality of their shopping experience. Sometimes, the inspectors will lay down steel plates at the entrance to aid the Camel Teams in moving heavy items. The inspection halls also open an inspection window designated for checking members’ passes. Even outside the duty-free zone, the Centre mandates that members deliver items to a designated area in the square near the entrance, where the items must be arranged systematically and not piled indiscriminately. The deliveries of small items adhere to a similar process, where the Camel heads have to either make multiple trips or hire additional camels to stay within the regulated limits. Customs and border inspectors typically do not perform extraordinary checks on camels who frequent the Centre and comply with the established quantity regulations. Through these measures, the Centre exerts comprehensive control and maintains discipline, ensuring that the activities of Camel Teams, often involving tax evasion, are regulated within the regulatory framework of the Centre, which thus can maintain orderly trade operations and play a vital role in the economic ecosystem of the border.

The enforcement of discipline on the Camel Teams can often be punitive rather than collaborative, reflecting the state’s control over their operations. The State Tobacco Monopoly Administration, a national-level authority, periodically dispatches officers to inspect the square outside the Centre, aiming to prevent duty-free cigarettes from reentering the domestic market. Surprise checks on postal couriers are also conducted for the same reason. Although these inspections do not directly result in financial losses for regular team members, they significantly disrupt merchants’ daily operations, affect the overall income of the Camel Teams, and force Camel heads to absorb these losses in order to maintain good relationships with border authorities, preserve team cohesion, and continue their operations despite the disruptions. Camel Teams have adapted their operations in response to these forms of punitive discipline, particularly since the Covid-19 pandemic. While their behavioural patterns remain similar to previous years, the teams have become more discreet. The standardisation of management at Khorgas Port has led to the disappearance of openly displayed goods at the Centre exit, and to the shifting of exchanges to designated shops across from the Centre. The teams are less visible. However, the rapid development of the Khorgas National Gate Scenic Area (Huo’erguosi guomen jingqu 霍爾果斯國門景區) has brought an additional influx of tourists. Despite stricter management, the number of Camel Teams has increased, with many now focusing on transporting smaller, more flexible items to navigate the heightened scrutiny. With urbanisation and the expansion of residential areas, shopping malls, and public services, the social dynamics of the Camel Teams have evolved. No longer solely a mobile workforce driven by economic necessity, the teams now encompass broader motivations, such as supplemental income, retirement activities, leisure, and community activities. These changes underscore how punitive disciplinary practices by the state have not only shaped the operations of the Camel Teams but have also influenced their social complexity and adaptive strategies.

Self-governed small markets under the influence of governmentality

The resilience of the Camel Teams in response to the increasingly punitive practices of the government is a prime example of the robust grassroots society in Khorgas, which has managed to establish and maintain market order despite government absence, disruptions, and discipline. Just outside the Centre, spaces such as the National Gate Small Market operate mainly through self-governance, though increasingly affected by the tacit guidance of both the central and local authorities. These examples illustrate the subtle workings of governmentality, where state power doesn’t rely solely on direct control but influences behaviour through indirect means, encouraging self-regulation and compliance within the framework of state interests. In these areas, marginalised subjects, who leverage the technologies of the self in their everyday border interactions, encounter a different kind of sovereignty. Engaging with the dynamics of power, identity, and resistance, they actively negotiate their place within the broader framework of sovereign practices, shaping their own autonomy in the process.

The Small Market emerged from the entrepreneurial spirit of local businesspersons, who capitalised on opportunities partly created by the inefficiencies in transportation management at the port. During the 1990s, the increase in border trade at Khorgas also lengthened the waiting time at customs, which prompted drivers and passengers to seek quick purchases of beverages and cigarettes during customs clearance or before resuming their journey. This area, remote and devoid of service stations for hundreds of kilometres, became ideal for small-scale commerce. Initially, vendors roamed with baskets or carts, selling sunflower seeds and beverages, thus establishing a dynamic, boundary-less floating market with no top-down policy design. In 1996, as the National Gate moved closer to the China-Kazakhstan border, the market also moved nearer to this new location and expanded to better serve the evolving needs of travellers from both countries. More importantly, the Small Market soon evolved into a key distribution centre for goods transported into China by the Camel Teams. Initially serving as a modest trading space, it became an essential link in the supply chain, where goods such as duty-free items, consumer products, and other high-demand commodities were discreetly exchanged. The flexibility of the Camel Teams in circumventing formal logistics channels allowed the Small Market to thrive, attracting merchants and customers alike. This informal distribution network provided an alternative to conventional trade routes, making it a vital part of the local economy and further entrenching the Small Market as a crucial destination for goods flowing across the border. In essence, the market’s role as a distribution centre supported local trade and highlighted the adaptive strategies of grassroots actors in navigating and profiting from the sovereign-imposed measures.

A peddler described the transformation of the Small Market, as well as the tension between the market and the government:

A few years ago, the National Gate Small Market primarily sold foreign cigarettes, which have now become “outdated goods” that no one cares about. [Now], Chinese cigarettes are brought out from the Centre and placed in the most prominent spots on the market stalls (…). However, these Chinese cigarettes are only supposed to be in the duty-free shops inside the Centre, and the Small Market is not authorised to sell them. Since the profit margin on these cigarettes is extremely high, most of the vendors still sell them. Whenever Tobacco Bureau officials come to inspect us, the vendors quickly hide the cigarettes to avoid confiscation. (Interview with XZZ, 28 July 2024)

Such tension may sometimes evolve into conflicts between grassroots vendors and the government. After 2000, the government became increasingly assertive as the Khorgas Port Management Committee opened the door to private investment and subsequently constructed permanent structures near the National Gate, attempting to formalising the previously self-governed market into a new state-run commercial area named National Gate Street. By 2002, the Khorgas government had erected three rows of buildings in the Gobi Desert, which provided much-needed parking facilities and established tourism amenities such as a rooftop viewing platform that the self-governed market could not independently provide. These state-dominated developments were designed to attract additional tourists and customers. Under state guidance, the market shifted its focus to primarily cater to tourists from Mainland China. Vendors began selling souvenirs from Kazakhstan and Central Asia, and in collaboration with border guards, implemented a fee-based system allowing private cars to cross the National Gate for fees ranging from RMB 200 to 300. These arrangements by the government significantly enhanced tourists’ engagement by providing them with intimate access to border markers and the border itself, which marked the inception of tourism development at Khorgas Port.

Despite the increasingly visible role of the government in infrastructure building and regulatory changes, the grassroot community in Khorgas maintains a significant degree of autonomy in commercial activities and some influence in reshaping state actions. The market, which had operated outside of formal legal frameworks for decades, survived intensified crackdowns by Khorgas’ urban management departments aimed at pushing them toward illegal status. Vendors engaged in a continued cat-and-mouse game with urban inspectors. Often mobile on tricycles, vendor usually temporarily fled the areas targeted by inspections, and then returned when it was safe. The need for vendors to constantly evade enforcement prevented them from establishing permanent business locations and prompted them to adopt skilful measures, such as painting their surnames along the highway to denote their selling spots. After years of struggles with these vendors, the local government accepted the fact that they should be allowed to do business with legal permits. Seizing the opportunity of the 2016 Silk Way Rally (an annual race held in Russia and neighbouring countries), the Khorgas government relocated the Small Market to a parking lot on the south side of the Asian-European Road and officially recognised it as the National Gate Small Commodity Market. Since 2019, following the inauguration of the South Gate, the Small Market has been phased out again due to stringent urban planning and epidemic control. However, the market reappeared following the lifting of the national lockdown, operating beyond the realms of sovereign power.

The prosperity of the Small Market, which facilitated the sale of foreign goods and catered to tourists, also partly contributed to the establishment of the Centre for that very purposes. Although the Centre has encroached on some of the business opportunities of the market, some businesspersons turned the market into a wholesale warehouse for tourists in order to effectively reduce operational costs. During slow seasons, some vendors join Camel Teams to make additional income. A few businesspersons with more resources established shops in the Centre for business expansion. In doing so, vendors continuously adjust and respond to the national governance practices that shape the development trajectory of Khorgas Port, which reflects a dynamic interplay between local entrepreneurship and state-driven economic strategies.

Conclusion

Khorgas is the most crucial land port within China’s Belt and Road Initiative, located in the geopolitically significant Central Asian area. As a vivid microcosm of the complex dynamics within China’s borderlands, Khorgas is a space where state sovereignty, local governance, and grassroots economic activity intersect and interact constantly. Inspired by the concept of dispositif, this research develops a three-level analytical framework – sovereignty, discipline, and governmentality – to understand the dynamics at play in Khorgas and similar border regions. At the level of sovereignty, this study finds that sovereignty becomes multiplied across the actual and internal borders, unevenly distributed among three national gates, and asymmetrically asserted by two states, with the more resource-rich China shouldering more sovereign responsibilities. Discipline, through which local officials act on behalf of the central state, operates through both formal and informal practices, as officials lack sufficient administrative resources to enforce the law to the letter and have to work tacitly with private actors, such as Camel Teams, who respond to the state’s punitive measures while often finding ways to circumvent direct control. Finally, at the level of governmentality, a more delicate form of control emerges, where local actors have negotiated and adapted within the state-imposed structures, highlighting the flexibility and resilience of self-governed grassroots economies. Together, these layers reveal how border spaces are shaped by both top-down regulations and by the everyday actions and adaptations of those who live and work within them, which strikes an evolving balance of power.

In addition to an analytical framework for border studies, this study further makes significant contributions to China studies by analysing how China manages its borders, especially in the strategic context of the Belt and Road Initiative, which balances state control with economic development. China’s global ambition amplifies the geopolitical importance of regions such as Khorgas, where national interests intersect with local realities to create both opportunities and challenges for border management.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all the participants of this research, including the team members and interviewees, in addition to the contributors of this issue. I am also grateful to the editors and anonymous reviewers of China Perspectives who have made this issue possible.

Manuscript received on 30 April 2024. Accepted on 2 October 2024.

References

AGAMBEN, Giorgio. 2009. “What Is an Apparatus?” and Other Essays. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

ALFF, Henryk, and Michael SPIES. 2023. “Coexistence or Competition for Resources? Transboundary Transformations of Natural Resource Use in China’s Neighborhood.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 64(7-8): 797-810.

Alff, Henryk, Talgarbay Konysbayev, and Ruslan Salmyrzauly. 2023. “Old Stereotypes and New Openness: Discourses and Practices of Trans-border Re- and Disconnection in South-eastern Kazakhstan’s Agricultural Sector.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 64(7-8): 896-918.

ANDERSEN, Dorte Jagetic, Martin KLATT, and Marie SANDBERG. 2016. The Border Multiple: The Practicing of Borders between Public Policy and Everyday Life in a Re-scaling Europe. London: Routledge.

BUSSOLINI, Jeffrey. 2010. “What is a Dispositive?” Foucault Studies 10: 85-107.

BRAMBILLA, Chiara, Jussi LAINE, and Gianluca BOCCHI. 2016. Borderscaping: Imaginations and Practices of Border Making. London: Routledge.

BRAMBILLA, Chiara, and Reece JONES. 2020. “Rethinking Borders, Violence, and Conflict: From Sovereign Power to Borderscapes as Sites of Struggles.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38(2): 287-305.

BRAUN, Bruce P. 2014. “A New Urban Dispositif? Governing Life in an Age of Climate Change.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32(1): 49-64.

CALLEWAERT, Staf. 2017. “Foucault’s Concept of Dispositif.” Praktiske Grunde 1-2: 29-52.

CHAMBERLAIN, James. 2021. “Challenging Borders: The Case for Open Borders with Joseph Carens and Jean-Luc Nancy.” Journal of International Political Theory 17(3): 240-56.

DEAN, Karin. 2020. “Assembling the Sino-Myanmar Borderworld.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61(1): 34-54.

DEAN, Mitchell. 2009. Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

DELANDA, Manuel. 2019. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London: Bloomsbury.

DELEUZE, Gilles. 1992. “What is a Dispositif?” In Timothy J. ARMSTRONG, and Georges CANGUILHEM (eds.), Michel Foucault: Philosopher. London: Pearson Professional Education. 159-68.

DELEUZE, Gilles, and Félix GUATTARI. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

DILLON, Michael. 2007. “Governing through Contingency: The Security of Biopolitical Governance.” Political Geography 26: 41-7.

DEAN, Karin, Jasnae SARMA, and Alessandro RIPPA. 2022. “Infrastructures and B/ordering: How Chinese Projects are Ordering China-Myanmar Border Spaces.” Territory Politics Governance 12(8): 1177-98.

ELDEN, Stuart. 2022. The Archaeology of Foucault. Cambridge: Polity Press.

ESMARK, Anders, and Peter TRIANTAFILLOU. 2009. “A Macro Level Perspective on Governance of the Self and Others.” In Eva SORENSEN, and Peter TRIANTAFILLOU (eds.), The Politics of Self-governance. London: Routledge. 25-41.

ESPOSITO, Roberto. 2012. “The Dispositif of the Person.” Law, Culture and the Humanities 8(1): 17-30.

FISCHER, Daniel X.O. 2018. “Situating Border Control: Unpacking Spain’s SIVE Border Surveillance Assemblage.” Political Geography 65: 67-76.

FOUCAULT, Michel. 2009. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-1978. London: Picador Books.

——. 2018. The Punitive Society: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1972-1973. London: Picador Books.

FROST, Tom. 2019. “The Dispositif between Foucault and Agamben.” Law, Culture and the Humanities 15(1): 151-71.

GEERTZ, Clifford. 1985. Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology. New York: Basic Books.

GILLES, Peter, Harlan KOFF, Carmen MAGANDA, and Christian SCHULZ (eds.). 2013. Theorizing Borders Through Analyses of Power Relationships. Bristol: Peter Lang.

GRANT, Andrew. 2020. “Crossing Khorgos: Soft Power, Security, and Suspect Loyalties at the Sino-Kazakh Boundary.” Political Geography 76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102070

GRIFFITHS, Mark, and Jemima REPO. 2018. “Biopolitics and Checkpoint 300 in Occupied Palestine: Bodies, Affect, Discipline.” Political Geography 65: 17-25.

JONES, Reece. 2012. “Spaces of Refusal: Rethinking Sovereign Power and Resistance at the Border.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102(3): 685-99.

JONES, Reeca, and Corey JOHNSON. 2016. Placing the Border in Everyday Life. London: Routledge.

KARRAR, Hasan H. 2022. “The Geopolitics of Infrastructure and Securitisation in a Postcolony Frontier Space.” Antipode 54(5): 1386-406.

KRICHKER, Dina. 2021. “Making Sense of Borderscapes: Space, Imagination and Experience.” Geopolitics 26(4): 1224-42.

LEGG, Stephen. 2011. “Assemblage/Apparatus: Using Deleuze and Foucault.” Areas 43(2): 128-33.

LIU, Binglin 劉炳林. 2018. 制造“駱駝隊”: 新疆霍爾果斯地區日常跨境流動研究 (Zhizao “luotuodui”: Xinjiang Huo’erguosi diqu richang kuajing liudong yanjiu, Making “Camel Team”: A study on the daily cross-border flow in Khorgas, Xinjiang.) MA Thesis. Beijing: Minzu University of China.

LIU, Xihong 劉璽鴻. 2018. 邊界“組裝”: 新疆霍爾果斯的邊界人類學考察 (Bianjie “zuzhuang”: Xinjiang Huo’erguosi de bianjie renleixue kaocha, Border assemblage: An anthropological study on the border in Khorgas, Xinjiang). MA Thesis. Beijing: Minzu University of China.

MAYER, Maximilian, and Xin ZHANG. 2021. “Theorizing China-world Integration: Sociospatial Reconfigurations and the Modern Silk Roads.” Review of International Political Economy 28(4): 974-1003.

MEGORAN, Nick. 2006. “For Ethnography in Political Geography: Experiencing and Re-imagining Ferghana Valley Boundary Closures.” Political Geography 25(6): 622-40.

MERRYMAN, Walter. 2021. “The Dispositif of Citizenship: Technology and Personhood in Iain M. Banks’s Culture.” Textual Practice 36(10): 1609-25.

MEZZADRA, Sandro, and Brett NEILSON. 2013. Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor. Durham: Duke University Press.

MOHANTY, Biswajit. 2023. “Border, Development and Dispossessed Agency.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 38(4): 563-84.

MOUNTZ, Alison. 2020. The Death of Asylum: Hidden Geographies of the Enforcement Archipelago. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

MURTON, Galen, Austin LORD, and Robert Beazley. 2016. “‘A Handshake across the Himalayas’: Chinese Investment, Hydropower Development, and State Formation in Nepal.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 57(3): 403-32.

MURTON, Galen. 2017a. Border Corridors: Mobility, Containment, and Infrastructures of Development between Nepal and China. PhD Dissertation. Boulder: University of Colorado.

——. 2017b. “Bordering Spaces, Practising Borders: Fences, Roads and Reorientations across a Nepal-China Borderland.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 40(2): 239-55.

MURTON, Galen, and Tom NARINS. 2024. “Corridors, Chokepoints and the Contradictions of the Belt and Road Initiative.” Area Development and Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2024.2311904

NEWMAN, David. 2023. “Three Decades of Border Studies: Whatever Happened to the Borderless World?” Beyond the Nation-States? Borders, Boundaries, and the Future of Democratic Pluralism. Salzburg Global American Studies program.

NGO, Tak-Wing, and Eva P. W. Hung. 2019. “The Political Economy of Border Checkpoints in Shadow Exchanges.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 49(2): 178-92.

——. 2024. “Gray Governance at Border Checkpoints: Regulating Shadow Trade at the Sino‐Kazakh Border.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 48(3): 488-505.

NIESWAND, Boris. 2018. “Border Dispositif and Border Effects. Exploring the Nexus between Transnationalism and Border Studies.” Identities 25(5): 592-609.

OLIVEIRA, Gustavo de L.T., Galen MURTON, Alessandro RIPPA, Tyler HARLAN, and Yang YANG. 2020. “China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Views from the Ground.” Political Geography 82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102225

ONG, Aihwa. 2006. Neoliberalism as Exception: Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty. Durham: Duke University Press.

PAASI, Anssi. 2012. “Border Studies Reanimated: Going beyond the Territorial/Relational Divide.” Environment and Planning A 44(10): 2303-9.

——. 2022. “Examining the Persistence of Bounded Spaces: Remarks on Regions, Territories, and the Practices of Bordering.” Geograifska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 104(1): 9-26.

PAINTER, Joe. 2006. “Prosaic Geographies of Stateness.” Political Geography 25(7): 752-74.

PANAGIA, Davide. 2020. “The Algorithm Dispositif: Risk and Automation in the Age of #datapolitik.” In Bishnupriya GROSH, and Bhaskar SARKAR (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Media and Risk. London: Routledge. 118-29.

PARKER, Noel, and Nick VAUGHAN-WILLIAMS. 2012. “Critical Border Studies: Broadening and Deepening the ‘Lines in the Sand’ Agenda.” Geopolitics 17(4): 727-33.

PFOSER, Alena. 2020. “Memory and Everyday Borderwork: Understanding Border Temporalities.” Geopolitics 27(2): 566-83.

PÖTZSCH, Holger. 2015. “The Emergence of iBorder: Bordering Bodies. Networks and Machines.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 33(1): 101-18.

RABINOW, Paul, and Nikolas S. ROSE. 2003. The Essential Foucault: Selections from Essential Works of Foucault, 1954-1984. New York: New Press.

RIPPA, Alessandro. 2019. “Cross-border Trade and ‘the Market’ between Xinjiang (China) and Pakistan.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 49(2): 254-71.

——. 2020. “Mapping the Margins of China’s Global Ambitions: Economic Corridors, Silk Roads, and the End of Proximity in the Borderlands.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 61(1): 55-76.

——. 2023. “Infrastructure Development in Xinjiang.” Oxford Research Encyclopedias. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.729

SALTER, Mark. 2008. “When the Exception becomes the Rule: Borders, Sovereignty, and Citizenship.” Citizenship Studies 12(4): 365-80.

SARMA, Jasnea, Hilary Oliva FAXON, and K. B. ROBERTS. 2022. “Remaking and Living with Resource Frontiers: Insights from Myanmar and Beyond.” Geopolitics 28(1): 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2022.2041220

SARMA, Jasnea, Alessandro RIPPA, and Karin DEAN. 2023. “‘We Don’t Eat those Bananas’: Chinese Plantation Expansions and Bordering on Northern Myanmar’s Kachin borderlands.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 64(7-8): 842-68.

SOHN, Christophe. 2016. “Navigating Borders’ Multiplicity: The Critical Potential of Assemblage.” Area 48(2): 183-9.

SPARKE, Matthew. 2006. “A Neoliberal Nexus: Economy, Security and the Biopolitics of Citizenship on the Border.” Political Geography 25(2): 151-80.

STANKIEWICZ, Łukasz, and Helena OSTROWICKA. 2020. “The Dispositif of Discipline and the Neoliberal Governance of Students.” In Helena OSTROWICKA, Justyna Spychalska-Stasiak, and Łukasz Stankiewicz (eds.), The Dispositif of the University Reform. London: Routledge. 114-48.

TANG, Waihong, and Elmira JOLDYBAYEVA. 2023. “Pipelines and Power Lines: China, Infrastructure and the Geopolitical (Re)construction of Central Asia.” Geopolitics 28(4): 1506-34.

TSAKHIRMAA, Sansar. 2022. “Comparative Ethnic Territorially-based Autonomy in Xinjiang, Tibet, Inner Mongolia and Ningxia of China 2010-2015: An Analytical Framework.” Journal of Contemporary China 31(138): 949-76.

WALTER, William. 2006. “Border/Control.” European Journal of Social Theory 9(2): 187-203.

——. 2015. “Reflections on Migration and Governmentality.” Movements Journal 41(12).

WICHUM, Ricky. 2013. “Security as Dispositif: Michel Foucault in the Field of Security.” Foucault Studies 15: 164-71.

WINTER, Tim. 2020. “Geocultural Power: China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” Geopolitics 26(5): 1376-99.

WU, Junjie 吳俊傑. 2021. “美好生活”的日常實踐: 基於新疆霍爾果斯“駱駝隊”的人類學研究 (“Meihao shenghuo” de richang shijian: Jiyu Xinjiang Huo’erguosi “luotuo dui” de renleixue yanjiu, Daily practice of “good life”: Based on the anthropological research of “Camel Team” in Khorgas, Xinjiang). MA Thesis. Beijing: Minzu University of China.

ZHAO, Xuan 趙萱. 2018. “國門與道路: 邊界的分化, 整合與超越 : 基於新疆霍爾果斯口岸的人類學研究” (Guomen yu daolu: Bianjie de fenhua, zhenghe yu chaoyue: Jiyu Xinjiang Huo’erguosi kou’an de renleixue yanjiu, National ports and roads: Differentiation, integration, and transcendence of borderlines. An anthropological study of Khorgas Port of Xinjiang). Yunnan minzu daxue xuebao (雲南民族大學學報) 35(4): 66-74.

——. 2022. “當代邊界治理中的安全與流動: 以霍爾果斯口岸為例” (Dangdai bianjie zhili zhong de anquan yu liudong: Yi Huo’erguosi kou’an wei li, Security and mobility in contemporary border governance: The case of the Khorgas Port.” Yunnan shifan daxue xuebao (雲南師範大學學報) 54(05): 44-53.

ZHAO, Xuan 趙萱, and LIU Xihong 劉璽鴻. 2018. “無交流的交通:日常跨界流動的人類學反思. 以霍爾果斯口岸‘中哈跨境合作中心’為例” (Wu jiaoliu de jiaotong: Richang kuajie liudong de renlei xue fansi. Yi Huo’erguosi kou’an “Zhong Ha kuajing hezuo zhongxin” wei li, Transportation without communication: An anthropological study of daily cross-border flows based on the China-Kazakhstan Cross-border Cooperation Center at the Horgos Port.” Yunnan shifan daxue xuebao (雲南師範大學學報) 50(6): 9-16.

——. 2019. “當代西方批判邊界研究述評” (Dangdai xifang pipan bianjie yanjiu shuping, A Review on critical border studies of contemporary west). Minzu yanjiu (民族研究) 1: 121-34; 142.

ZHAO, Xuan 趙萱, and WU Junjie 吳俊傑. 2020. 常人之境 : 中國西北邊地口岸人的口述 (Changren zhi jing: Zhongguo xibei biandi kou’an ren de koushu, The realm of the common people: Oral accounts of people at the borderland crossings in northwest China). Beijing: Jiuzhou chubanshe.

ZHURZHENKO, Tatiana. 2023. “Between the ‘Opening to the West’ and the Trauma of Rebordering: Towards a Genealogy of Post-Soviet Border Studies.” In Sabine von LOWIS, and Beate ESCHMENT (eds.), Post-Soviet Borders: A Kaleidoscope of Shifting Lives and Lands. London: Routledge. 32-50.

[1] Binglin Liu, Xihong Liu, and Junjie Wu are all Master’s students mentored by the author, and members of the research team.