BOOK REVIEWS

Playing with Fire: How Engagement with Illicit Economies Shapes the Survival and Resilience of Ethnic Armed Organisations in the China-Myanmar Borderlands

Xu Peng is a PhD candidate at the Department of Politics and International Studies, SOAS University of London, 10 Thornhaugh St, London WC1H 0XG, United Kingdom (687318@soas.ac.uk).

Introduction

Northern Shan State, one of Myanmar’s largest and most ethnically diverse administrative areas in the China-Myanmar borderlands, has experienced conflicts for decades. This region is simultaneously governed by various ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) which engage in illicit economies intertwined with China.[1] Notably, three “China-facing groups” – the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA) – have deep economic ties with China, particularly through the Belt and Road Initiative, including the development of industrial zones and transportation corridors (Tønnesson, Oo, and Aung 2022) (Figure 1). Despite these groups’ active economic engagement, such links have not translated into enhanced border stability. Instead, the ongoing escalation of conflict has led to severe refugee crises and border insecurity.

Figure 1. Map of three special regions in the China-Myanmar borderlands of northern Shan State

Credit: created by the author.

Note: according to Myanmar Government nomenclature, the following regions are classified as self-administered regions: Shan State Special Region 1 (MNDAA, the “Kokang group”), Special Region 2 (the “Wa group”), and Special Region 4 (NDAA, the “Mong La group”).[2]

Specifically, this article examines the Kokang and Wa armies in northern Shan State, whose interactions with China have significantly impacted them. UWSA, the largest EAO in Myanmar, is heavily involved in border trade with China and maintains a high level of autonomy in Myanmar. Kokang’s army, the MNDAA, is known for its rebellious posture, its ties to illicit economies, and involvement in ongoing conflicts. Following a raid on a factory by the Myanmar military in 2009, hostilities escalated with the MNDAA, leading to its defeat and the transformation of Kokang forces into the Kokang Border Guard Force (BGF). After a severe clash in 2015, 100,000 refugees fled to China, raising border security concerns on China’s policy agenda. The “1027 Operation” in October 2023, involving the MNDAA, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Arakan Army (AA), marked yet another significant episode in this protracted conflict, with a coordinated offensive against the Myanmar military. Complex interactions between illicit economies and cross-border dynamics further complicate the security situation, affecting both countries.

Previous research into northern Shan State conflicts has primarily employed state-centric and holistic approaches. The state-centric approach suggests that the extent of the state’s governance ability in border regions contributes to the prevailing chaos. This narrative often argues that the weakness of the Myanmar state, especially in terms of its inability to maintain ceasefire agreements with the EAOs, leads to a power-sharing political status in northern Shan State. The asymmetrical capacities among China, Myanmar, and Thailand further compound this chaotic situation. Myanmar’s inability to assert control over its borderlands is partly attributed to historical political and military interference from its more powerful neighbours (Han 2019: 20-35). Significant research adopts a holistic approach, revealing the intertwined roles of EAOs, illicit economies, and state-building from a political economy perspective. It argues that the Myanmar state’s involvement in the illicit economy, especially the drug trade, has constructed and reproduced the state’s power (Meehan 2011). This deep integration of Myanmar state-building in northern Shan State, illicit economies, and the presence of various non-state armed groups has been further exacerbated by the broader context of Southeast Asia’s “battlefields into marketplaces” since the 1980s – an aspiration to move beyond Cold War era political divisions towards a more prosperous, collective future (Dwyer 2022: 101). Aligning with this transformation, the concept of “ceasefire capitalism” describes violent counterinsurgency waves that have replaced warfare in targeting the politically suspicious, resource-rich, ethnically populated China-Myanmar borderlands since the ceasefire agreements signed in the early 1990s by the Myanmar military and the EAOs (Woods 2011).

The aforementioned research shows that the persistence of the illicit economy, driven by cross-border trade between China and Myanmar, is closely linked to the fragmented sovereignty in northern Shan State (Su 2018). However, it has not addressed how armed groups in the China-Myanmar borderland have responded to the global Covid-19 pandemic since 2020, particularly how they adapted to the closing and reopening[3] of the state-to-state border and their subsequent engagement in the growing digital illicit economy, specifically online scams. Growing reports of the rise of “online scam warlords”[4] in the China-Myanmar borderlands have attracted international attention, due to their links to widespread digital fraud and human trafficking in Southeast Asia and also because escalating regional conflicts since 2023 have raised questions about China’s potential involvement. This concern is amplified by the fact that Chinese citizens have been the primary targets of these online scams, and previous countermeasures against such scams have proven ineffective.[5]

This raises the question of how these armed groups in northern Shan State have transformed their methods of generating revenue, particularly from the traditional border trade with China, to extend beyond China’s geographical borders. Thus, this article aims to uncover the interactions between EAOs and illicit economies and to explore how these interactions have changed over time. Additionally, it examines the distinct agendas and strategies of EAOs in various stages, investigating how these groups establish and maintain legitimacy within their communities, the socioeconomic motivation behind local communities’ involvement in drug cultivation, and the broader implications of such practices. Finally, it considers the fundamental question of survival, seeking to understand why the persistence of an illicit economy is vital for EAOs and what motivates their continual adaptation and resilience amidst ongoing challenges. By addressing these multifaceted aspects, the research intends to provide a comprehensive understanding of the roles and impacts of EAOs within the sociopolitical and economic frameworks of northern Shan State.

This article is derived from my PhD project at SOAS, titled Borderland Statecraft and Temporality in the China-Myanmar Borderland: The Ethnic Armed Organisation History of the Wa and Kokang, spanning from 2020 to 2024. The extensive fieldwork, conducted from 2018 to 2022 across multiple sites in the China-Myanmar and Thai-Myanmar borderlands engaged diverse participants, including borderlanders, border patrol officers, ex-combatants of the EAOs, and brokers. Private connections and academic collaborations with Yunnan University and Chiang Mai University facilitated access to this field site.

The extensive historical scope of this article, covering various periods from the Cold War to post-Cold War, posed significant challenges, necessitating the selective presentation of materials to effectively illustrate the evolving dynamics within the borderlands. Thus, data collection integrated interviews, photographs capturing the political landscape (such as the securitisation of the borderlands, forms of illicit economy or the presence of military posts), as well as archival materials and open-access reports. The article is presented with a historical focus, drawing heavily on previous literature and newspaper sources to analyse the drug trade during the Cold War. For more contemporary issues, such as gambling and online scams, the study mainly utilised selected interviews with brokers in border counties in Yunnan and open-access reports. This approach provided an understanding of both the historical evolution and current challenges faced by EAOs within the illicit economies of the borderlands.

This article employs a spatiotemporal approach to trace the evolution of revenue-generating interaction modes among EAOs in the China-Myanmar borderlands, transitioning from traditional methods such as drug trading and gambling to contemporary practices such as online scams. It argues that the survival and adaptability of EAOs are fundamentally influenced by four interconnected factors: border openness/closure, transnational flows, EAOs’ strategies, and types of illicit economy. The analysis is supported by a multidimensional flowchart that illustrates three types of interaction mechanisms. Initially, it examines the lucrative drug trade that enabled EAOs to build primitive capital, shaping factional drug warlord governance during the Cold War. The narrative then transitions to the period from 2000 to 2020, when EAOs shifted their strategies towards seeking legitimacy by adopting the gambling industry as a more sustainable revenue source than drug trafficking. This strategic shift coincided with increasing cross-border mobility, leading to more porous borderlands in the China-Myanmar region. Lastly, the closure of borders between China and Myanmar during the Covid-19 pandemic compelled EAOs to adapt once again, this time turning to the digital realm with online scams to sustain their operations and initiate a new phase of capital accumulation.

This article aims to contribute to the expanding scholarship on the political and economic transformations shaping the contested borderlands in two ways. Firstly, examining the resilience of EAOs reveals that their ability to balance revenue-generating measures and their political status over time demonstrates strong adaptive strategies for survival. Rather than being manipulated by states, they are highly flexible, adjusting their political status through various revenue-generating measures. This ultimately offers a micro-level perspective to explain their persistence in conflicts within contested borderlands. Second, as one of Myanmar’s significant neighbours, China has inevitably exerted influence in this peripheral region. Understanding the connections between EAOs and the illicit economy in the China-Myanmar borderlands provides an alternate narrative beyond the failure of weak state governance, offering deeper insights into China’s interests and policies regarding Myanmar. It specifically aids in understanding how China balances its border security concerns with its broader state-to-state interests, particularly as its influence in Southeast Asia continues to expand.

This article is organised into three main sections: The first section critically examines the existing literature on the illicit economy and EAOs in the China-Myanmar borderland, tracing the shift from viewing the illicit economy as a remnant of Cold War era conflicts to analysing the political status and dynamics of non-state armed groups in the post-Cold War environment. The second section identifies gaps in current research and introduces a spatiotemporal approach to explore the dynamics between border openness/closure, transnational flows, EAO strategies, and illicit economy types. The third section analyses the transformation of the illicit economy from the drug trade and gambling to online scams, and discusses how EAOs have adapted their strategies in response to these changes.

From war legacies to modern political dynamics: Evolving analysis on illicit economies and EAOs in the China-Myanmar borderlands

Tracing the origins of illicit economies: Insights from war economy research

The connection between illicit economies and non-state armed groups is a common phenomenon across conflict zones globally, often emerging in postwar contexts where weakened state authority creates a power vacuum.[6] Following the Cold War, with reduced external support, non-state armed groups increasingly turned to alternative revenue streams, including trading in oil, minerals, timber, and narcotics (Ballentine and Nitzschke 2005). These actors often collaborate with businesses and intermediaries across borders to integrate these goods into the global market.

Shadow economies in conflict settings frequently involve networks of organised crime, mafia-type structures, or pre-war controllers of illicit trade. This political-criminal nexus, characterised by decentralised systems reliant on illicit commerce, is considered a legacy of war economies (Andersen 2010). Although postwar state-building efforts, such as regulating the logging industry in Liberia (ibid.), aim to curtail the scale of illicit economies, they often fall short. Instead, high-profit ventures such as the drug trade have grown, further complicating efforts to dismantle these shadow economies. At the micro-level, the durability of illicit economies is supported by transactional relationships between armed groups and local communities, offering mutual benefits of protection and revenue, a dynamic notably observed in West Africa (Felbab-Brown and Forest 2012). While such economies enhance the armed groups’ capabilities and political leverage, they do not inherently provoke broader military conflicts. Rather, the illicit economy’s role is more about ensuring the day-to-day survival of these groups. However, armed conflicts can amplify, transform, and shift the patterns of narcotics production (Cornell 2007), bolstering the strength of insurgent movements at the expense of state power. In summary, the discourse on the illicit economy-armed group nexus is evolving, with recent studies drawing parallels between non-state combatants and organised crime groups using criminal proceeds as a “war resource.”[7]

Like other international conflict zones, the presence of the illicit economy in the China-Myanmar borderland has been an integral aspect of war economies. However, the dynamics at this border are particularly complex, deeply rooted in the intertwined histories of the Myanmar civil war and the Cold War’s broader context in Southeast Asia. The pivot to illicit economies, notably the drug trade, emerged as a survival strategy for ethnic armed groups along the border following the 1962 military coup led by the Ne Win government,[8] which dismantled Myanmar’s federal system and ignited widespread struggles for autonomy (Smith 1999: 27-38). This tumultuous period coincided with the height of the Cold War in Southeast Asia, during which the China-Myanmar borderland became a strategic front, perceived by the US as a crucial buffer to contain communist expansion. The region’s geopolitical significance attracted various external supports for local armed factions, aligning them with pro- or anti-communist movements depending on the geopolitical allegiances of their backers (Steinberg and Fan 2012: 93-119). A notable instance of this complex web of alliances and support mechanisms is the involvement of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) forces during the 1950s. The CIA’s support facilitated the KMT’s involvement in the opium trade in part to counter China’s communist influence. During this period, the Golden Triangle became a more important heroin production hub, with the US playing a pivotal role in its transportation (McCoy, Read, and Adams 1972: 14).

Examining the persistence of illicit economy: Categorising political status and non-state armed groups

Since the end of the Cold War, analysing the complex situation in the China-Myanmar borderland has evolved beyond simply tracing the legacies of war economies. This approach is insufficient to explain exceptional cases, especially why some non-state armed groups achieve different political statuses and what role they play in illicit economies. Instead, recent research categorises the political status and non-state armed groups in the China-Myanmar borderland, offering a nonlinear perspective on the formation of fragmented sovereignty.

Recent research differentiates the political statuses in the post-Cold War era in the China-Myanmar borderland, identifying various stages between peace and war, such as ceasefire conditions. This liminality – a term describing a transition between stages – is exemplified by some EAOs. For instance, Andrew Ong’s anthropological research of the UWSA in 2021 introduces the concept of “tactical dissonance” to describe the group’s shifting political stances, alternately aligning with the Myanmar state or asserting independence to resist control and maintain autonomy. His 2023 publication investigates how the Wa navigate external pressures towards sovereignty and manage the complexities of borderland geopolitics and the shadow economy, proposing that these factors explain the persistent stalemate with the Myanmar government.

Apart from further differentiating political statuses in the China-Myanmar borderland, a significant shift from the war economy legacy involves distinguishing between various non-state armed groups. These groups are categorised based on their proximity to the Myanmar military, highlighting that not all ethnic armed groups maintain adversarial relationships with the incumbent state. Specifically, militias – paramilitary-style organisations closely aligned with and regulated by the Myanmar military – exemplify this.[9] Their involvement in illicit economies often serves dual purposes – both their survival demands and the broader Myanmar state-building process. The Myanmar state’s involvement in the drug trade, for instance, facilitates governance through mechanisms such as legal impunity and coercion, incorporating militias into a system of “brokered rule” alongside the military and illicit trade, emphasising their role as intermediaries (Meehan 2011; Meehan and Dan 2023).

Spatiotemporal approach: Mechanism of the illicit economy-EAO survival nexus

Previous research on the illicit economy and EAOs in the China-Myanmar borderlands has evolved from focusing on the legacies of the war economy to further delineating various political statuses and non-state armed groups, thereby complicating the situation. However, a critical question remains insufficiently addressed: how and why do these non-state armed groups interact with the incumbent state (Myanmar) and the neighbouring state (China) over time, and in what ways do these interactions reshape borderland rules? Understanding these interactions is crucial not only for comprehending the dynamics of the illicit economy in the China-Myanmar border but also for explaining the adaptability of non-state armed groups in navigating relationships between China and Myanmar.

This article proposes using a spatiotemporal approach to trace EAOs’ revenue-generating interaction modes over time, borrowing from urban and historical sociology. This method analyses phenomena by considering both their spatial and temporal dimensions. This article discusses spatiality derived from Henri Lefebvre’s influential 1974 work The Production of Space, which argues that space is actively constructed through social processes, power dynamics, and interactions. In the context of borderland studies, it is essential to view borderlands not as two separate entities but as integrative parts of a single continuum, which Baud and van Schendel (1997) subdivided into the border heartland, intermediate, and outer borderland. Recent borderland studies have expanded on Lefebvre’s ideas, exploring spatial dynamics such as the “border effect,” as discussed by Annette Idler (2019: 21) in the context of Colombia’s violent non-state group interactions; Enze Han’s (2019: 10) “neighbourhood effect,” highlighting asymmetrical power dynamics among China, Myanmar, and Thailand; and Teo Ballvé’s (2020: 9) “frontier effect,” which examines the perceived statelessness and resultant state-building efforts in Colombian frontiers.

In historical sociology, it is crucial to consider the temporal dimension to investigate the conditions influencing social events. Charles Tilly highlighted the significance of sequencing in historical events, observing that ‘‘When things happen within a sequence affects how they happen’’ (1984: 14). The progression of time allows for an examination of how specific variables influence the trajectory of events across various temporal stages. Immanuel Wallerstein’s (2004: 23-41) world-system theory introduces a socioeconomic system and argues that the world is made up of core, peripheral, and semi-peripheral areas. Similarly, in borderlands studies, Michiel Baud and Willem van Schendel (1997) suggest that borderlands undergo a unique temporal progression, which they describe metaphorically as a ‘‘life cycle’’ ranging from embryonic to defunct stages, highlighting the distinctive temporal dynamics of these regions. However, this approach has been criticised by William Sewell (1990) for its linear, teleological perspective. Theda Skocpol in States and Social Revolutions (1979: 33-40) attempts to set up comparative ‘‘natural experiments’’ capable of sorting out the causal factors that explain the occurrence of social revolutions. This is categorised as experimental temporality (Sewell 1990) and contests linear, teleological perspectives by highlighting the multi-sequences in which events unfold.

The discussion of spatiality reveals the nature of multi-layered complexities in borderlands, while the discussion on temporality highlights the multi-sequences’ role in understanding these regions. Willem van Schendel and Itty Abraham (2005: 4-6) promote and apply a spatiotemporal approach to analyse the persistence of illicit economies in borderlands. They do this by redefining the spatial dimensions of nation-states and viewing the present as a temporal pivot in the varied historical attempts at regulation. Applying this approach sheds light on the revenue-generating modes of EAOs in the China-Myanmar borderlands for three key reasons. Firstly, recognising EAOs as border actors embedded in temporal processes acknowledges their fluid political status and their capacity for strategic adaptation, illustrating their dynamic rather than static nature. Secondly, the circumstances of EAOs, particularly within their borderland context, are equally dynamic, evolving through various developmental stages of the borderland itself. Lastly, it highlights how the interactions between border actors and their environment are not only dynamic but also reciprocally influential across different historical periods, affecting both the actors and the borderlands in a cyclical manner.

The shifting strategies of EAOs

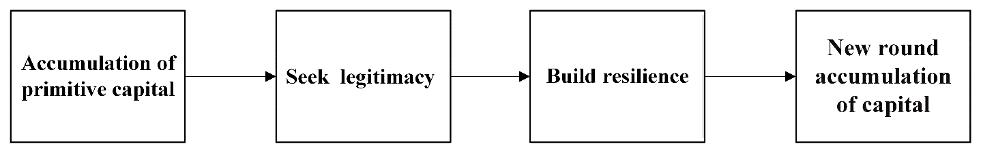

This study explores the relationship between EAOs’ survival, resilience, and engagement in the illicit economy. The analysis builds upon the strategic development stages identified: accumulation of primitive capital, seeking legitimacy, building resilience, and further capital accumulation (Figure 2).

The progression through these stages illustrates how EAOs adapt to and shape their economic environment to ensure their survival and growth. To capitalise on the border economy’s opportunities, EAOs employ specific strategies at each stage. Initial capital accumulation is essential to establish a foothold and support basic operations, setting the stage for more sophisticated interactions with both the local economy and the wider border.

In the stage of seeking legitimacy, the case studies illustrate how EAOs transform from mere insurgents to recognised stakeholders, or vice versa if they fail to secure legitimacy. Beyond political gain, this is a strategic move to secure their operations and facilitate smoother interactions with economic actors across the border. Legitimacy allows EAOs to access resources and networks previously restricted by political and legal constraints. Armed groups achieve legitimacy through diverse strategies, including representing a community’s socioeconomic and political aspirations, projecting external threats, leveraging leaders’ charisma, demonstrating a willingness to sacrifice, and drawing upon communal myths and traditions (Terpstra and Frerks 2017). According to Podder (2017), relationships with three key groups shape an armed group’s legitimacy: the civilian population it claims to represent, the incumbent state, and the international community, including external patrons. In this context, EAOs in the China-Myanmar borderland can seek legitimacy either from their community, the Myanmar government, or external patrons such as China.

Building resilience is a critical phase where EAOs strengthen their capacity to withstand external pressures and shocks (Weinstein 2007: 260-96). The findings suggest that resilience is not solely about military might but also involves creating diversified economic practices to prepare EAOs to handle disruptions and maintain operations amidst fluctuating border policies and market conditions.

In the new round of accumulation of capital, EAOs engage in advanced economic activities that often blend traditional illicit ventures with more formal economic engagements, leveraging the stability and networks established in earlier phases. This stage is marked by a sophisticated integration of the EAOs into the border economies, where they play significant roles as military entities and economic influencers. This analysis reveals a continuous and dynamic interplay between these stages and the illicit economy.

Figure 2. EAOs’ shifting strategies

Credit: author.

It is important to recognise the possibility of changes in EAOs’ political status in Myanmar. While this paper examines the role played by EAOs, EAOs represent just one category within the broader spectrum of intermediary non-state armed groups within Myanmar’s complex history of conflict. Other key groups include pro-military militias and BGF, which consist of co-opted former EAOs serving military interests. Depending on Myanmar’s political climate, these EAOs may fluctuate between being staunchly anti-government and autonomous entities to being supported or even orchestrated by the Myanmar military. The discourse surrounding the Shan State along the China-Myanmar borderlands transcends the political identities of EAOs. This is particularly evident in the case study analysis of the Kokang MNDAA, an EAO, and the Kokang BGF, supported by the Myanmar government. This analysis reveals how these groups interact across four relationship stages in areas governed by these parallel regimes, ultimately leading to a dynamic of mutual substitution.

‘‘Border as resources’’

The concept of “border as resources” usually focuses on the advantages of borders for border populations rather than on their constraints (Feyissa and Höhne 2010). Christophe Sohn (2020: 71-88) expands on the concept of “borders as resources” by introducing the notion of “opportunity structures,” which highlights the structural aspects beyond individuals’ control that influence the development and success of border practices. While small trade and smuggling are well-studied border opportunities, the benefits of borders extend beyond the economic realm. Borders also serve as zones for political manoeuvring, allowing groups to gain autonomy, forge collective identities, and secure legal rights, such as refugee status (Feyissa and Höhne 2010). Additionally, the concept of “borders as resources” gained traction with the increasing cross-border cooperation and regional integration in Europe and North America beginning in the 1990s (O’Dowd 2002).

The concept of the “border as resources” helps explain how border actors – EAOs in the China-Myanmar borderland – utilise border conditions, whether open, closed, or porous, to their advantage. In this context, “border permeability,” which refers to the degree of border openness influenced by economic factors such as infrastructure development and security measures, including border policies and enforcement, is regarded as a critical resource. This degree of border openness, or its absence, can both drive and result from the actions of EAOs. Thus, EAOs can capitalise on high border openness to enhance the transnational flows of goods, money, and people. Simultaneously, they can also exploit the region’s instability and conflicts for political manoeuvring, reshaping the borderland in the process. This article argues that EAOs’ revenue-generating modes should be seen as dynamic, interactive models with varying starting and ending points that evolve over time.

The flowchart in Figure 3 illustrates the complex interactions between border openness/closure, transnational flows, EAOs strategies, and types of illicit economy with multilayer and sequence features. The diagram uses three types of arrows to represent different interaction scenarios. Initially, during the period from 1950 to 1990 (red dashed arrows, first interaction), the emphasis was on how the drug trade facilitated the accumulation of primitive capital of the EAOs and accelerated the transactional flows, which ultimately widened the border. From 2000 to 2020 (green dotted arrows, second interaction), the focus shifted from changes in the EAOs’ strategy to seeking legitimacy through non-drug trade, such as the gambling industry. The rising gambling industry, in turn, along with smuggling behaviours, led to increasing porousness of the borderland. The most recent phase, from 2020 onwards (blue solid arrows, third interaction), started with the increased securitisation and closing of borders due to global events such as the Covid-19 pandemic, prompting EAOs to pivot towards online scams as a means of resilience and to initiate a new cycle of capital accumulation.

This mechanism highlights how border actors (specifically EAOs) utilise borders, suggesting that borders can both influence and result from their actions. Each phase features distinct strategies and starts and ends at different points, reflecting this multi-layered and sequential mechanism. This mechanism is depicted through arrows pointing in different directions, illustrating that border openness/closure is not the sole determinant of economic behaviour; rather, it is part of a broader spectrum that also includes the existing illicit economy (first interaction) and shifts in the strategies of border actors (second interaction).

Figure 3. Three interaction mechanisms of border openness/closure, transnational flows, EAO strategies, and illicit economies

Credit: author.

From drug trade to gambling to online scams

First interaction, 1950-1990s: Drug trade, accumulation of primitive capital, border openness

This section explores the strategic involvement of EAOs in the drug trade, rooted in the porous China-Myanmar borderland. Combined with long-standing social networks and the region’s complex ethnic diversity, this borderland’s permeability facilitated the transit of goods and the entrenchment of illicit economies. These dynamics have historically enabled EAOs to accumulate primitive capital through the drug trade. With these illicit activities, EAOs have secured essential resources for their survival and expansion, leveraging the loosely regulated border to sustain their operations. This section reveals how the preexisting economic form – drug trade – shaped EAO’s strategy, leading to the factional drug warlord scenarios in the China-Myanmar borderlands during the Cold War.

Golden Triangle drug trade routes[10] span Myanmar, China, Thailand, and Laos, influenced by historical migrations and regional geopolitics. The cultivation and trade of opium date back centuries, with significant expansion during colonial times (Kim 2020). Poppy cultivation was not a major cash crop in the region until foreign intervention in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. With the British East India Company seeking markets for its drug produced in India, opium was integrated into the local economies of Southeast Asia, including Thailand, which established a royal opium franchise. In the early twentieth century, Thailand took a more direct role in managing the drug trade and generating substantial revenue.[11]

Between the late 1970s and 1990, China mostly served as a drug trafficking transit route, linking the Golden Triangle with lucrative markets such as Hong Kong and the US.[12] During and after World War II, the Golden Triangle became a major opium-producing area due to political and social upheavals. The utilisation of opium as political leverage by armed groups in negotiations with the Myanmar military illustrates a complex dynamic (Chin 2009: 86-126). Initially, armed groups aligned with the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) heavily depended on the opium trade for financial sustenance. In response, the Myanmar government implemented the Ka Kwe Ye (KKY) programme in the 1960s to recruit ethnic armies to combat communist insurgents in Shan State, offering them incentives to control cross-border trade. KKY aimed to weaken communist forces by diverting their primary revenue source – the drug trade. With permission from the Myanmar government, the KKY engaged in the drug trade, acquiring advanced weaponry from the black markets in Thailand and Laos (Lintner 1994: 232). However, the KKY programme had the unintended consequence of indirectly financing other armed groups (Priamarizki 2020). During the Cold War, this development enabled various ethnic groups to accumulate capital, strengthen their forces with new recruits, expand or secure their territories, and occasionally set up basic governance structures. These drug warlords also vied for control over trade routes.

As Myanmar’s drug trade routes became increasingly profitable, a notable conflict emerged in Shan State between two armed groups: the UWSA and the Mong Tai Army (MTA), which had long competed over these lucrative drug trade routes.[13] The MTA, situated in the eastern part of Myanmar adjacent to Thailand, expanded its influence throughout Shan State. Meanwhile, the UWSA, another regional rising power, increasingly clashed with the MTA’s ambitions. The MTA’s goal to establish the Republic of Shan State raised concerns within the Myanmar government, which had limited control over this borderland area (Zhong and Li 2004: 197-201). Recognising mutual benefit, the Myanmar government allied with the UWSA to counter the MTA’s expansion.[14] During a series of conflicts, the UWSA emerged victorious, taking over territories formerly held by the MTA, which were subsequently incorporated into what is now known as the Southern Wa Region (Shi 2012: 137-9).

The two case studies – the KKY program from the 1960s to the 1980s, and the conflicts between two armed groups in Shan State during the 1990s – illustrate that the drug trade has been instrumental not only in amassing initial capital for these groups but also in serving as political capital to negotiate power dynamics between EAOs and the incumbent state. This scenario highlights more than just internal conflicts among EAOs; it emphasises how the control of drug trafficking routes, especially during the booming drug trade amid the Cold War, became a significant lever for political manoeuvring. These dynamics helped the UWSA and similar groups forge and maintain power alliances, ultimately shaping the factional drug warlord scenarios in the China-Myanmar borderland during the 1990s. This strategic use of illicit activities underscores the complex interplay between economics and politics in influencing the regional dynamics of Shan State.

Second interaction, 2000-2020: Legitimacy, gambling, border openness

In contrast to the initial interaction driven by the drug trade, which enabled the accumulation of primitive capital for EAOs and established the factional rule of drug warlords in the borderlands during the Cold War, the second interaction emerged from a strategic shift within the EAOs. By transitioning from the stigmatised narcotics trade to the more socially accepted gambling industry, the EAOs not only sought to gain legitimacy but also transformed the type of illicit economy. This shift from drug trafficking to the burgeoning gambling sector was accompanied by an increase in illegal border crossings – particularly stowaways (toudu 偷渡) and associated smuggling of goods – with the predominant rise in the frequency and volume of people sneaking across the border significantly contributing to the increased porousness of the borderlands.

The establishment of Kokang’s casino industry, a significant economic shift from drug trade to gambling, can be traced back to the post-1989 ceasefire agreement between the Myanmar government and Kokang’s local authorities (which mainly refers to Kokang MNDAA)[15] (Myint Myint Kyu 2018: 17). Similarly, the Wa region, another former faction of the CPB, negotiated autonomy from the Myanmar government in exchange for peace.[16] This negotiation aimed to legitimise their political status by transitioning to sustainable economic development, thus moving away from their historical association with the drug trade. Beyond gaining recognition from the incumbent state and neighbouring China,[17] this shift of strategy also aimed to achieve international recognition. This transition was implemented by a series of stringent anti-drug campaigns,[18] reflecting a determined effort to align with international anti-narcotics standards (Kramer 2007).

Following the establishment of the first official welfare lottery in 1987 (Wang and Antonopoulos 2015), the Chinese government made concerted efforts to curb the development of uncontrolled gambling practices (Liu 2012: 7-8). This regulatory tightening during the 1990s[19] in Mainland China inadvertently created unique opportunities for EAO-controlled regions such as Wa and Kokang. These regions attracted numerous visitors and investments, particularly from Chinese investors and gamblers, who were seeking alternatives to the restricted gambling avenues available in Mainland China. This influx transformed these areas into vibrant economic and cultural hubs, spurred the growth of entertainment complexes, and attracted a diverse workforce to Kokang. These developments have positioned Kokang as an emerging economic centre, with ambitions to develop Laukkai, the capital town of Kokang, into a premier gambling destination, reflecting broader aspirations to enhance its economic profile through the gambling industry.[20]

Fieldwork conducted in 2018 in Nansan Town, a border town adjacent to Kokang in the China-Myanmar borderland, reveals the remarkable accessibility of the gambling industry. Observations show how individuals can traverse the border from Nansan Town in the Chinese border county of Zhenkang to Kokang in Myanmar, often without valid identification. The journey typically starts at the Nansan coach station. After disembarking, passengers are approached by motorcyclists offering rides to Laukkai for a fee of RMB 200-300 (Figure 4). This arrangement often bypasses official checkpoints via hidden paths, highlighting a systematic and openly discussed smuggling operation rather than a covert activity. In an ironic twist, individuals entering Myanmar “illegally” encounter checkpoints operated by the Kokang BGF, which levies “fees” for smuggling. Once these fees are paid, individuals gain unfettered access to Kokang, with casinos frequently being their first destination. Further insights from the same fieldwork highlight how the gambling industry caters to a wide range of patrons by allowing bets as low as RMB 5-10. This inclusivity makes gambling accessible to migrant workers and others deterred by higher financial thresholds. These findings align with 2019 research by La Seng Aung, Seo Ah Hong, and Sariyamon Tiraphat, which identified various popular gambling activities among internal migrants on the China-Myanmar borderland, including lottery games (Aung Bar Lay, Nhit-Lone, Thone-Lone),[21] card games, and electronic gambling machines.

Figure 4. The free shuttle bus between casinos in Kokang to Nansan Town in Yunnan

Credit: photo taken by the author in Kokang, 2018.

More importantly, the presence of the gambling industry significantly increases cross-border mobility, leading to heightened smuggling activities that are conspicuously embedded within the daily lives of borderland communities. In an interview conducted in 2018, a broker I met in Laukkai, referred to as “D,” remarked:

It’s very convenient to cross the border between China and Myanmar, and there are many hidden paths in the deep mountains. Many gamblers from Mainland China smuggle into Kokang because they can’t get a border pass [a permit limited to border residents or legal workers in China’s border county]. So, they hire motorbikes to take them across [to Kokang]. Smuggling isn’t very expensive, and some gamblers spend only a few days in Kokang’s casinos before returning to Mainland China. (Interview with broker D, 27 February 2018, Laukkai, Kokang, Myanmar)

Rather than viewing these activities strictly as smuggling, brokers such as D see them as a way to profit from Mainland China, despite expressing frustration over the high fees imposed by the Kokang BGF for crossing into Kokang. By facilitating and overseeing access to gambling and related smuggling activities, these armed groups not only gain economic benefit but also reshape the degree of border openness. This reshaping influences how borders are crossed and managed, affecting the broader dynamics of the region. This alteration in border openness involves a complex interaction with the state, where EAOs manage ceasefires and conflicts to maintain their autonomy and functional governance without necessarily resorting to violence.

Third interaction, 2020-present: Border closure, resilience, and new round accumulation of capital, online scams

Compared to the second stage, where EAOs shifted strategies to establish legitimacy through gambling, the third stage emerged from changes in border openness, directly influencing EAOs’ strategies and the types of illicit economy they engaged in. This transition was catalysed both by the global health crisis that was Covid-19, and increased border securitisation, which dramatically curtailed transnational flows. The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and the erection of a 2,000-kilometre fence along the China-Myanmar border (see Figure 5)[22] not only disrupted preexisting networks but also compelled EAOs to significantly adapt their economic behaviours.[23]

The shift to a digital illicit economy – particularly online scams – emerged as a tactical adaptation in response to enforced border closures, marking the beginning of a new round of capital accumulation. This strategic pivot reflects a broader trend observed across the region, with an Asia Foundation report noting a decline in road transport, a vital revenue source for many EAOs.[24] The disruption in traditional revenue streams may explain increased civilian abductions and other alternative fundraising mechanisms, indicating a significant transformation in EAO economic activities due to external pressures.[25]

In response to these constraints, EAOs increasingly turned to digital avenues, leading to a surge in online scams carried out within the China-Myanmar borderlands. In 2023, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) highlighted a distressing trend, noting that upwards of 120,000 individuals in Myanmar and an additional 100,000 in Cambodia may be trapped in conditions forcing them to engage in various online scams.[26] These range from illegal gambling to cryptocurrency fraud, establishing a direct link between the pandemic and a surge in online illicit activities. Reports from credible sources, including the OHCHR, suggest that Myanmar hosts numerous scam centres. Allegedly located in territories such as Shwe Kokko and Myawaddy on the Thai border, as well as the KK Park (KK yuanqu, KK 園區), a known ‘‘fraud factory’’ in Myawaddy, and compounds along the Moei River, these centres also extend to the Kokang Self-administered Zone (SAZ) in Shan State and Mong La on the Chinese border, among others.

Figure 5. Iron gauze built up on the China-Myanmar border

Credit: photo taken by the author in Menglian Dai, Lahu and Va Autonomous County, Yunnan, China, 3 December 2021.

Compared to the traditional illicit economies of the drug trade and gambling, the online scam industry represents a paradigm shift. Unlike its predecessors, it transcends time and space constraints and is not dependent on the porous physical borderlands. This industry benefits from remote operations, generating profits significantly faster than earlier illicit activities. EAOs near the Chinese border have adeptly transitioned their economic reliance from traditional border trade to recruiting illegal labour for the digitally organised sector of online scams. Importantly, the expansion of the online scam industry does not necessarily require China to reopen its borders, as the labour for these operations can be sourced through illegal crossings from various countries, including Thailand. This demonstrates a broad operational reach that bypasses the need for open border crossings, specifically with China.

When China closed its borders with Myanmar, illegal crossings often occurred via irregular channels, utilising smugglers and intermediaries to circumvent the costly and inaccessible regular migration pathways. Thailand has become an increasingly significant transit country for these operations, with individuals travelling to Thailand before being trafficked over the border to Myanmar or moved between scam operations across Southeast Asia. Fieldwork conducted along the Thai-Myanmar border in 2022 revealed that, despite the pandemic, clandestine routes between Thailand and Myanmar remained operational (Figure 6). In contrast to the stringent border controls enforced by China, the informal crossings between Thailand and Myanmar persisted, albeit at increased cost compared to the pre-Covid period.

This situation has led to the development of what Franceschini, Li, and Bo (2023) call “compound capitalism,” a new form of predatory capitalism. “Compounds” refer to the locations housing online scam operations, effectively restricting workers’ movements. These compounds are often specially designed for online activities, comprising offices, dormitories, shops, entertainment facilities, and other amenities. In some instances, they are integrated with or located near casinos, occupying office buildings or the upper floors of a licensed casino. In other cases, they are situated within condominiums or apartment complexes. This is further reinforced by the well-organised structure of the scam industry, which includes departments for human resources, scams, accounting, and logistics (ibid.). This evolution into compound capitalism reflects a new form of predatory capitalism by exceptionality, labour segregation, forceful data extraction, and reliance on the desperation of workers.

Figure 6. Wa village on the Myanmar side, crossing from the Thai border from Mae Hong Son

Credit: photo taken by the author in 2022.

In addition to facilitating a new round of capital accumulation for EAOs, the digital illicit economy mirrors the role played by the drug trade during the 1990s conflicts among EAOs, serving as political capital that can influence and potentially transform their political status. A significant example of this dynamic occurred on 27 October 2023, when the MNDAA, in collaboration with two other EAOs, launched a significant offensive against the Kokang BGF backed by the Myanmar government – predominantly overseen by the “four families” (Bai, Wei, Ming, and Liu)[27] ostensibly to dismantle extensive online scam operations. This campaign, which rapidly seized more than 100 positions and established control over several key towns,[28] including the strategically crucial Chinshwehaw, effectively used online scam allegations to justify military actions and reshape the geopolitical and territorial landscape of the borderlands.[29]

Ultimately, MNDAA regained its territory after losing in the 2009 Kokang incidents. This “return home”[30] victory has been widely discussed, especially in terms of how MNDAA synchronised its military action with China’s crackdown on online scams, highlighting a strategic alignment. This suggests a sophisticated manipulation of political narratives, where criminality is deployed as leverage for military objectives and territorial control. This adaptation and the issuance of Chinese government warrants against individuals involved in online scams indicate an astute exploitation of border dynamics to potentially secure recognition or cooperation from China by addressing mutual cybersecurity threats. This scenario exemplifies how the governance of illicit economies serves as both a pretext for conflict and a diplomatic tool, reflecting a broader shift in the strategies of non-state armed actors. More importantly, it illustrates how EAOs strategically decide when to engage, expand, or withdraw from the illicit economy, using these moves to leverage external actors.

Conclusion

This article examines the complex relationships between EAOs and illicit economies in the China-Myanmar borderlands of northern Shan State. Utilising a spatiotemporal approach, it identifies three interconnected mechanisms – lucrative illicit economies, shifts in EAO strategies, and changes in border openness/closure – and explores how these factors interact through the drug trade (1950-1990s), gambling (2000-2020), and online scams (2020-present).

These insights reveal a dynamic interplay where changes in border openness/closure, strategic shifts by EAOs, and the nature of illicit economies collectively drive the evolution and persistence of these economies. The mechanisms identified do not merely sustain these economies but also continually transform the socioeconomic landscape of the borderlands.

However, it is also important to recognise that presenting the transitions from the drug trade to gambling to online scams as a straightforward sequence might underestimate the intricate symbiotic relationships among these activities. In reality, each stage mutually influences and is influenced by the others, indicating a complex web of interdependence. This dynamic interaction is exemplified by the continued presence of drugs, particularly crystal methamphetamine, which shows that earlier stages of illicit activity do not vanish but evolve in response to shifting dynamics. As such, the drug trade persists alongside newer economic activities such as online scams, illustrating how various forms of illicit economies are interconnected and impact the strategic adjustments of EAOs. Future research should explore how these illicit economies interconnect, coexist, and mutually influence each other within the broader sociopolitical landscape.

Acknowledgements

This article was completed as part of my PhD project at SOAS during the writing-up year, funded by the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation (CCKF) Doctoral Fellowship in 2024. It greatly benefitted from Tianlong You’s invitation to contribute to the special feature on China borderlands. I am also grateful to Zizhu Wang from Sussex for my brainstorming sessions and to the SOAS Southeast Asian Workshop Series in 2024 for the opportunity to present these preliminary findings. It has benefitted from the professional and detailed feedback of two anonymous reviewers, who possess profound insights into Myanmar politics and its connections with Chinese borderlands. Lastly, I also express my thanks to Marie Bellot and Justine Rochot from China Perspectives for facilitating the whole editing and publishing process.

Manuscript received on 21 May 2024. Accepted on 24 September 2024.

References

ANDERSEN, Louise. 2010. “Outsiders Inside the State: Post-conflict Liberia between Trusteeship and Partnership.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 4(2): 129-52.

AUNG, La Seng, Seo Ah HONG, and Sariyamon TIRAPHAT. 2019. “A Descriptive Study of Gambling Practices and Problem Gambling Among Internal Migrants in Muse, Northern Shan, Myanmar.” Nagoya Journal of Medical Science 81(1): 133-41.

BALLENTINE, Karen, and Heiko NITZSCHKE. 2005. “Introduction.” In Karen BALLENTINE, and Heiko NITZSCHKE (eds.), Profiting from Peace: Managing the Resource Dimensions of Civil War. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. 1-24.

BALLVÉ, Teo. 2020. The Frontier Effect: State Formation and Violence in Colombia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

BAUD, Michiel, and Willem van SCHENDEL. 1997. “Toward a Comparative History of Borderlands.” Journal of World History 8(2): 211-42.

CHIN, Ko-lin. 2009. ‘‘Heroin Production and Trafficking.’’ In Ko-lin CHIN, The Golden Triangle: Inside Southeast Asia’s Drug Trade. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 86-126.

CORNELL, Svante E. 2007. “Narcotics and Armed Conflict: Interaction and Implications.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 30(3): 207-27.

DWYER, Michael B. 2022. Upland Geopolitics: Postwar Laos and the Global Land Rush. Seattle: University of Washington Press. 98-127.

FELBAB-BROWN, Vanda, and James J. F. FOREST. 2012. “Political Violence and the Illicit Economies of West Africa.” Terrorism and Political Violence 24(5): 787-806.

FEYISSA, Dereje, and Markus Virgil HÖHNE. 2010. Borders and Borderlands as Resources in the Horn of Africa. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer.

FRANCESCHINI, Ivan, Ling LI, and Mark BO. 2023. “Compound Capitalism: A Political Economy of Southeast Asia’s Online Scam Operations.” Critical Asian Studies 55(4): 575-603.

HAN, Enze. 2019. Asymmetrical Neighbors: Borderland State Building Between China and Southeast Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

HENSHAW, Andrew. 2024. Understanding Insurgent Resilience: Organizational Structures and the Implications for Counterinsurgency. London: Routledge.

HU, Zhiding, and Victor KONRAD. 2018. “In the Space between Exception and Integration: The Kokang Borderlands on the Periphery of China and Myanmar.” Geopolitics 23(1): 147-79.

IDLER, Annette. 2019. Borderland Battles: Violence, Crime, and Governance at the Edges of Colombia’s War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

KIM, Diana S. 2020. Empires of Vice: The Rise of Opium Prohibition across Southeast Asia. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

KRAMER, Tom. 2007. The United Wa State Party: Narco-army or Ethnic Nationalist Party? Washington: East-West Center.

LEFEBVRE, Henri. 1974. The Production of Space. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

LINTNER, Bertil. 1994. Burma in Revolt: Opium and Insurgency since 1948. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

LIU, Xi. 2012. The Legalization of Casino Gambling in Mainland China. PhD Dissertation. Las Vegas: University of Nevada.

MEEHAN, Patrick. 2011. “Drugs, Insurgency and State-building in Burma: Why the Drugs Trade Is Central to Burma’s Changing Political Order.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 42(3): 376-404.

MEEHAN, Patrick, and Seng Lawn DAN. 2022. “Brokered Rule: Militias, Drugs, and Borderland Governance in the Myanmar-China Borderlands.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 53(4): 561-83.

McCOY, Alfred W., Cathleen B. READ, and Leonard P. ADAMS. 1973. The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia. New York: Harper Colophon Books.

MYINT MYINT KYU. 2018. Gambling as Development: A Case Study of Myanmar’s Kokang Self-administered Zone. Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development (RCSD), Chiangmai University. https://rcsd.soc.cmu.ac.th/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/UMD07_GamblingasDevelopment.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2024).

O’DOWD, Liam. 2002. “The Changing Significance of European Borders.” Regional & Federal Studies 12(4): 13-36.

ONG, Andrew. 2021. ‘‘Tactical Dissonance: Insurgent Autonomy on the Myanmar-China Border.’’ American Ethnologist 47: 369-86.

———. 2023. Stalemate: Autonomy and Insurgency on the China-Myanmar Border. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

PODDER, Sukanya. 2017. “Understanding the Legitimacy of Armed Groups: A Relational Perspective.” Small Wars and Insurgencies 28(4-5): 686-708.

PRIAMARIZKI, Adhi. 2020. “Ka Kwe Ye to Border Guard Force: Proxy of Violence in Myanmar.” Ritsumeikan International Affairs 17: 43-64.

SEWELL, William H. Jr. 1990. “Three Temporalities: Toward a Sociology of the Event.” Centre for Research on Social Organization. CSST Working Paper 58. Deep Blue (University of Michigan). https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/51215/448.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2024).

SHI, Lei 石磊. 2012. 守望金三角 (Shouwang jinsanjiao, Guarding the Golden Triangle). Hong Kong: Tianma chubanshe.

SKOCPOL, Theda. 1979. States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia and China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SMITH, Martin. 1999. Burma: Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London: Zed Books.

SOHN, Christophe. 2020. “Borders as Resources: Towards a Centring of the Concept.” In James W. SCOTT (ed.), A Research Agenda for Border Studies. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. 71-88.

STEINBERG, David I., and Hongwei FAN. 2012. Modern China-Myanmar Relations: Dilemmas of Mutual Dependence. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

SU, Xiaobo. 2018. “Fragmented Sovereignty and the Geopolitics of Illicit Drugs in Northern Burma.” Political Geography 63: 20-30.

———. 2022. “Smuggling and the Exercise of Effective Sovereignty at the China-Myanmar Border.” Review of International Political Economy 29(4): 1135-58.

TERPSTRA, Niels, and Georg FRERKS. 2017. “Rebel Governance and Legitimacy: Understanding the Impact of Rebel Legitimation on Civilian Compliance with the LTTE Rule.” Civil Wars 19(3): 279-307.

TILLY, Charles. 1984. Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

TØNNESSON, Stein, Min Zaw OO, and Ne Lynn AUNG. 2022. “Pretending to be States: The Use of Facebook by Armed Groups in Myanmar.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 52(2): 200-25.

van SCHENDEL, Willem, and Itty ABRAHAM. 2005. Illicit Flows and Criminal Things: States, Borders, and the Other Side of Globalization. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

VORRATH, Judith. 2018. “What Drives Post-war Crime? Evidence from Illicit Economies in Liberia and Sierra Leone.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal 3(1): 28-45.

WANG, Peng, and Georgios A. ANTONOPOULOS. 2015. “Organized Crime and Illegal Gambling: How Do Illegal Gambling Enterprises Respond to the Challenges Posed by Their Illegality in China?” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 49(2): 258-80.

WALLERSTEIN, Immanuel Maurice. 2004. World-systems Analysis: An Introduction. Durham: Duke University Press.

WEINSTEIN, Jeremy. 2007. Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

WOODS, Kevin. 2011. “Ceasefire Capitalism: Military-private Partnerships, Resource Concessions and Military-state Building in the Burma-China Borderlands.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 38(4): 747-70.

ZHONG, Zhixiang 鐘智翔, and LI Chenyang 李晨陽. 2004. 緬甸武裝力量研究 (Miandian wuzhuang liliang yanjiu, Myanmar armed groups research). Beijing: Junshi yiwen chubanshe.

[1] Seng Lawn Dan, 2022, “Conflict and Development in the Myanmar-China Border Region,” Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT), https://www.xcept-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Report_Conflict-and-Development-in-the-Myanmar-China-Border-Region.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2024).

[2] Shan State Special Region 3, located in central and eastern Shan State and away from the China-Myanmar border, contrasts with other special regions. Unlike the other three special regions, which had historical ties to China as former members of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), Shan State Special Region 3 lacks such connections. This geographical and historical distinction explains why it is often excluded from research maps focusing on the dynamics of the China-Myanmar borderland.

[3] China closed its borders with Myanmar in early 2020 and reopened in early 2023. This closing and reopening mainly refers to the official state-to-state checkpoints.

[4] Nectar Gan, “How Online Scam Warlords Have Made China Start to Lose Patience with Myanmar’s Junta,” CNN, 19 December 2023, https://edition.cnn.com/2023/12/19/china/myanmar-conflict-china-scam-centers-analysis-intl-hnk/index.html (accessed on 5 August 2024).

[5] “Scam Centres and Ceasefires: China-Myanmar Ties since the Coup,” International Crisis Group, 27 March 2024, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/north-east-asia/china-myanmar/b179-scam-centres-and-ceasefires-china-myanmar-ties-coup (accessed on 20 August 2024).

[6] “Human Development Report 2011: Sustainability and Equity: A Better Future for All,” United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/human-development-report-2011-english.human-development-report-2011-english (accessed on 3 April 2024).

[7] Ekaterina Stepanova, “Armed Conflict, Crime and Criminal Violence,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Yearbook 2010, https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2010/02 (accessed on 3 April 2024).

[8] This period marks a crucial phase in Burma’s history. U Nu had led the country since 1948 as Prime Minister of Burma, but his leadership came under increasing pressure from military leader Ne Win. In 1958, Ne Win led a “soft” coup d’état, initially leading a caretaker government to “stabilise” the nation, then stepping aside to let U Nu assume control again, and finally, launching a final coup d'état and heralding in a military dictatorship that, with the exception of the brief 2015-2021 democratic transition, has ruled Myanmar since.

[9] John Buchanan, “Militias in Myanmar,” The Asia Foundation, July 2016, https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Militias-in-Myanmar.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

[10] Another major set of routes leads west and south from the Golden Triangle into Thailand and Laos, respectively. These routes have been used to transport narcotics to Bangkok and other urban centres, from where they can be distributed domestically or exported internationally. The Mekong River, which flows from China through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam, has been a critical artery for the movement of goods, including opium and heroin. The river facilitates access to remote areas and the movement of enormous quantities of narcotics.

[11] Bertil Lintner, “The Golden Triangle Opium Trade: An Overview,” Asia Pacific Media Services, March 2000, https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=d995643cba3b41347cc1708a47eafdb48e64e60f (accessed on 5 April 2024).

[12] Niklas Swanström and Yin He, “China’s War on Narcotics: Two Perspectives,” Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program, December 2006, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/30100/03_China_War_Narcotics.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

[13]“Chronology for Shans in Burma, 1990-2006” Minorities at Risk (MAR), http://www.mar.umd.edu/chronology.asp?groupid=77507 (accessed on 11 April 2024).

[14] Western officials observed that the Wa received support from Myanmar’s government, including transportation, artillery, and logistics assistance. Additionally, they benefitted from the Thai government’s cooperation, which permitted the Wa forces to traverse Thai territory to deploy their troops in combat. “Myanmar: Rebel ‘Opium King’ Under Siege,” The Los Angeles Times, 24 September 1990, https://www.newspapers.com/image/176612052/?match=1&terms=%22Mong%20Tai%20Army%22%20 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

[15] The local authorities referenced here are distinct from the Kokang Self-administered Zone (SAZ) established by the 2008 Constitution of Myanmar, which was officially recognised in 2010 following the 2009 Kokang incident. During this conflict, the MNDAA lost control of the territory, and the Kokang BGF, backed by the Myanmar military, took over Kokang. The SAZ is governed by these BGF authorities and is considered illegitimate by the MNDAA.

[16] Compilation Committee of Wa State Chronicles of Myanmar 緬甸聯邦佤邦志編撰委員會, 2018, 緬甸聯邦佤邦志 (Miandian lianbang wabang zhi, Wa chronicles of Myanmar), p. 5.

[17] Zhenkang Foreign Affairs Office 鎮康外事, “鎮康縣禁毒委員會與果敢緬政府官員舉行禁毒會晤” (Zhenkang xian jindu weiyuanhui yu guogan mian zhengfu guanyuan juxing jindu huiwu, Anti-drug meeting between Zhenkang County Anti-drug Committee and Kokang Myanmar government officials), 6 January 2000 (accessed on 1 February 2022, Zhenkang Archive, Yunnan Province).

[18] Peng Jiasheng 彭家聲, “全民行動起來, 打一場消滅毒品的人民戰爭” (Quanmin xingdong qilai, da yichang xiaomie dupin de renmin zhanzheng, All people should take action to fight the people’s war against drugs), MNDAA’s Headquarter Publishing, 10 June 1996 (accessed on 1 February 2022, Zhenkang Archive, Yunnan Province).

[19] State Council of the People’s Republic of China 中華人民共和國國務院, 1992, “關於堅決制止賽馬博彩等賭博性質活動的通知” (Guanyu jianjue zhizhi saima bocai deng dubo xingzhi huodong de tongzhi, Notice on firmly curbing gambling activities such as horse race betting and other gambling activities). This does not imply that China only began to prohibit gambling in 1992: the ban officially started as early as 1949, but this regulatory document indicates a reinforcement of the official prohibition on gambling in the 1990s, echoing the larger context of “moral crisis” which marked the 1990s in China.

[20] Nanda, “The Kokang casino dream,” Frontier Myanmar, 23 July 2020, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/the-kokang-casino-dream/ (accessed on 8 April 2024).

[21] Aung Bar Lay is a monthly official state lottery; Nhit-Lone is an illegal lottery where winning numbers are derived from the last two digits of daily Thai stock exchange numbers; and Thone-Lone is an illegal lottery which uses the last three digits of the Thai state lottery's biweekly results (Aung, Hong, and Tiraphat 2019).

[22] Sebastian Strangio, “China Building Massive Myanmar Border Wall: Reports,” The Diplomat, 17 December 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/12/china-building-massive-myanmar-border-wall-reports/ (accessed on 3 April 2024).

[23] Priscilla A. Clapp and Jason Tower, “Myanmar Regional Crime Webs Enjoy Post-coup Resurgence: The Kokang Story,” United States Institute of Peace (USIP), 27 August 2021, https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/08/myanmar-regional-crime-webs-enjoy-post-coup-resurgence-kokang-story (accessed on 4 April 2024).

[24] “Covid-19 and Complex Conflicts: The Pandemic in Myanmar’s Unsettled Regions,” The Asia Foundation, September 2021, https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Myanmar_Covid-19-and-Complex-Conflicts_ENG.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2024).

[25] The report further uses cases of TNLA and argues that by the end of 2021, TNLA and Shan State Progress Party forces operated as far afield as Mogok in Mandalay Region, allegedly abducting business owners for extortion or as punishment for alleged drug trafficking, highlighting the extent of Covid-19’s economic impacts in the region.

[26] “Hundreds of Thousands Trafficked into Online Criminality Across SE Asia,” UN News, 29 August 2023, https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/08/1140187 (accessed on 6 April 2024).

[27] The “four [big] families” of northern Myanmar, or Kokang, are headed by Bai Suocheng, Wei Chaoren, Liu Guoxi, and Liu Zhengxiang, all local Kokang people (ethnic Han Chinese). They control the mining, commerce, and real estate business in Laukkai, the capital of the Kokang SAZ in northern Myanmar. Behind the scenes, the families are also involved in illicit activities such as telecom scams and gambling.

[28] Morgan Michaels, “Operation 1027 Reshapes Myanmar’s Post-coup War,” Myanmar Conflict Map - International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), November 2023, https://myanmar.iiss.org/updates/2023-11 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

[29] Nectar Gan, “How Online Scam Warlords (…),” op. cit.

[30] Yaolong Xian, “Good Rebels or Good Timing?: Myanmar’s MNDAA and Operation 1027,” The Diplomat, 5 January 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/01/good-rebels-or-good-timing-myanmars-mndaa-and-operation-1027/ (accessed on 20 August 2024).