BOOK REVIEWS

Translocating Trajectories, Transnational Mobilities: The Cross-border Migration and Livelihoods of Hmong in the Tri-state Area Between China, Vietnam, and Laos

Tian Shi serves as Lecturer at Wenzhou University’s College of Overseas Chinese, Chashan Higher Education Park, Ouhai District, Wenzhou, China (shitianchina@hotmail.com).

Introduction

The highland territories of the Southeast Asian Massif which span across China, Vietnam, and Laos (Michaud 2009: 27) have historically served as a refuge for various groups fleeing centralised regimes, failed rebellions, and oppressive policies. Formerly emblematic of the concept of the “art of not being governed” (Scott 2009), the region, hereafter designated as “tri-state area,” has witnessed a significant change in its politico-economic landscape in recent decades. Since 2010, China has been increasingly regarded as a key player and sponsor in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Cooperation Program (Colin 2014: 107). Vietnam’s recent policy shift towards enhancing cross-border trade and investment has also markedly contributed to regional economic integration and cooperation (Mellac 2014: 148), and even Laos, a landlocked state, has created and strengthened its global ties through its memberships in the GMS, the ASEAN, and the WTO (Sisouphanthong 2014: 175). These bilateral and multilateral economic collaborations, agreements, and regulatory frameworks have cultivated a fertile market environment in this tri-state area.

This economic boom, which draws a diverse cohort of investors and businesspersons from China’s interior to its Southeast Asian neighbours (Nyíri and Tan 2017: 7), modifies the traditional ways of life and livelihoods of ethnic minorities (Michaud and Forsyth 2011; Wilcox 2021: 129-32). More than 200 million highlanders of various ethnic backgrounds (Forsyth and Michaud 2011: 1) have increasingly engaged with modern governance frameworks (Kuah 2000; Chan 2013). State authority complicates their quest for control through contradictory agendas, while remaining anxious about their presence in the borderlands (Saxer, Rippa, and Horstmann 2018: 4). Ethnic groups, in response, have to navigate and react to border policies at multiple levels (Qian, Yang, and Tang 2023; Thi, Xuan, and Thi 2024), which are often unfavourable to them (Michaud and Forsyth 2011). This suggests the necessity to understand the dynamics, innovations, and conflicts present within their responses.

The Hmong, numbering over four million across this area (Culas and Michaud 2004: 71), constitute a particularly interesting example as far as adaptation and resilience is concerned. The Hmong’s experience, as observed by scholars, is one of seizing opportunities to thrive as microentrepreneurs and small business owners (Turner, Bonnin, and Michaud 2015; Turner, Derks, and Rousseau 2022; Rumsby 2023), which have opened new avenues for upward social mobility among the ambitious youth (Wilcox 2021: 41; Lee 2024). Meanwhile, scholars have underscored the substantial disadvantage that marginalised ethnic minorities experience within the dynamic economic landscapes of Southeast Asia (Turner 2018; Wilcox 2021). Yet, the full extent of their transborder mobility, as it intersects with local and global governance frameworks, remains an area ripe for further exploration.

This study seeks to uncover how the interplay of the trilateral South-South cooperation shapes opportunities, choices, and mobilities in the tri-state area, as well as how the Hmong harness external forces, traditional knowledge, and their agency to carve out livelihoods in this transnational space. The article investigates the experiences of Hmong entrepreneurs, focusing on their strategies and agency. It goes beyond highlighting the successes of their businesses and lives to shed light on the challenges and hardships they have faced. Despite the difficulties, the cases presented in this article show how these entrepreneurs have learned valuable lessons and used them to shape their strategies in response to the ever-changing political and economic landscapes in the tri-state area, all while grappling with uncertainties about the future.

Literature review

South-South cooperation

South-South cooperation has become increasingly vital for Southeast Asian countries (Engel 2019) as it fosters regional integration, economic development, and stability in areas with diverse socioeconomic and political landscapes (Chaturvedi 2017). This cooperation underscores the exchange of knowledge, skills, resources, and technical expertise within the framework of mutually beneficial partnerships (Mawdsley 2024: 206), addresses common challenges such as poverty, infrastructure deficits, and environmental degradation (Gray and Gills 2016), and promotes peace and security across borders by fostering mutual understanding and interdependence (Chaturvedi 2017). Thus, South-South cooperation, despite the competing interests and zero-sum power dynamics among these nations, fosters economic growth but also plays a pivotal role in creating a balanced and interconnected Southeast Asian region.

Through numerous multiple-level programmes, including the West Development Project, the Bridgehead Project (qiaotou bao zhanlüe 橋頭堡戰略),[1] and the Belt and Road Initiative, China has developed a comprehensive transportation network that links its well-developed coastal areas and less developed interiors with Southeast Asian neighbours (Nyíri and Tan 2017: 8-10). On a smaller scale, but with significant impact, the Lao government has also invested heavily in transport infrastructure, aiming at enhancing the trade and investment environment and maximising the benefits of increased connectivity and integration (Sisouphanthong 2014: 187-8). This robust infrastructure, jointly developed by three countries with their own respective agendas concerning competing influences and power, is significantly reshaping the economic, political, and social landscapes of the region.

Existing studies on South-South cooperation often adopt a top-down and macro perspective, concentrating on the policy implementations supporting macroeconomic stability, and emphasising sectors such as investment in improving agricultural productivity, food security, infrastructure, etc. (Chaturvedi 2017). However, the priorities and goals of a state may not always align with the interests of different groups and individuals within/across its borders. Thus, this broad perspective tends to overlook micro-level factors such as the nuanced interactions, resilience, and negotiation strategies among multiple ethnic groups. Furthermore, as China’s influence grows, positioned by some scholars as a new “donor” (Bry 2017), its impact on Southeast Asian neighbours significantly alters the dynamics of cross-border ethnic migration. It calls for a sophisticated reevaluation of how these dynamics are understood and managed in the context of China’s rise, and how South-South cooperation affects cross-border ethnic groups such as the Hmong and their migration patterns within the context of multilayered governance and interaction with various (contradictory) actors.

Border policies in this tri-state area

Cross-border labour migration is often facilitated by loose migration policies and the historical kinship and cultural ties that span these nations (Rumsby and Gorman 2023). In pursuit of economic growth, dramatic shifts in border policies occurred in China following its reform and opening up policies initiated in the late 1970s (Kuah 2000: 73), in Vietnam with its economic renovation starting in the mid-1980s (Mellac 2014: 148), and in Laos through economic reforms beginning in 1986 (Sisouphanthong 2014: 176). While all three are governed by communist regimes, their interactions have been characterised by fluctuations, conflicts, and tensions, as well as periods of peace and prosperity, which significantly influence their border policies. The borders between these countries were not fully and officially reopened until 1991, when China and Vietnam signed a resolution to normalise their bilateral relationship and resume cross-border trade (Kuah 2000: 75-6). This tri-state area was thus able to exert influence beyond the borders as it was integrated into the global economy quickly and deeply.

While expressing an interest in border security and managing “crypto-separatist” ethnic minorities (Wilcox 2021: 95-8), the collaboration between three nations has led to loosening border policies and improved infrastructure. Saxer, Rippa, and Horstmann (2018: 3-4) highlighted the significance of infrastructure development in borderlands to integrate peripheries into states and promote cross-border trade while regulation facilities bolstered state initiatives aimed at biopolitical interventions and exerting control. This observation was particularly evident during the Covid pandemic, when China constructed barbed-wire fences in its border regions. These altered border policies have compelled cross-border ethnic communities to devise adaptive strategies to address diverse circumstances. Qian, Yang, and Tang (2023) and Thi, Xuan, and Thi (2024) illustrated that the pandemic and the end of rigid lockdown regulations prompted a shift to more flexible, negotiated forms of mobility for border residents along the Sino-Vietnam and Sino-Myanmar borders. In line with this trend, this study investigates how the Hmong population in the tri-state area has navigated shifting border policies and tapped into niche markets.

Scholars have criticised the academic literature on migration in Southeast Asia for focusing solely on the role of governments in recognising the human rights of non-citizens, while overlooking other relevant regional mechanisms, actors, and agents that play a crucial role in shaping migration (Petcharamesree and Capaldi 2023: viii). Moreover, empirical studies indicate that the intricate features of borders as mobilised, contested, integrated, and engaged in everyday crossings contribute to the construction/destruction of infrastructure and inclusion/exclusion (Reeves 2014: 6). Therefore, there is a need to examine intersections, hybridity, and multi-level mobility in borderlands.

Migrant entrepreneurship as a form of livelihood

Migrant entrepreneurship is often classified into two forms: middleman entrepreneurship and enclave entrepreneurship (Zhou 2004). According to Zhou’s research, middleman minority groups serve as essential intermediaries, connecting dominant group producers with minority customers. They help bridge status gaps and establish businesses in low-income areas, despite often encountering hostility from the host community (Min 2017). For instance, extensive research has highlighted the benefits of middleman entrepreneurship within the Overseas Chinese community (Zhou 2004; Liang 2023). In Laos, Chinese and Vietnamese migrants participate in entrepreneurial forms of migration, which categorises them as a middleman minority (Molland 2017: 345).

Enclave entrepreneurs, on the other hand, create niches that cater predominantly to their own ethnic communities, fostering a sense of cultural continuity and community cohesion (Light and Gold 2000). In a study conducted by Liang (2023), the exploration of undocumented immigrants in the informal labour market highlighted the impact of immigrant-owned employment agencies in introducing market institutions, sharing work opportunities, and fostering enclave entrepreneurship. Through these enclave businesses, immigrant communities maintain their cultural heritage and contribute significantly to the cultural diversity and economic vitality of their host countries.

In the Indochinese Peninsula, previous studies have referenced groups such as Muslim caravanners (Michaud and Culas 2000: 103), Hmong or Yao traders (Turner 2018: 50-2), and other ethnic “upland pioneers” (Stolz and Tappe 2021) as either middleman or enclave entrepreneurs. Studies in Vietnam and Laos have gradually started recognising ethnic migrant entrepreneurs who have shaped their life paths and economic success through (in)formal economies across borders. Turner, Derks, and Rousseau (2022) highlighted the close and enduring collaboration between ethnic intermediaries in the global spice industry over time. This emerging area therefore calls for more empirical studies to understand ethnic migrant entrepreneurship in the tri-state area.

Hmong: A transborder ethnic minority in the evolving tri-state area

Roughly a century ago, the Hmong people migrated from China to Southeast Asian countries and established “more or less permanent settlements” across Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam (Michaud 1997), mainly within the tri-state area. The Hmong have frequently encountered various contradictory policies that may often be averse to their interests. Similarly, the resettlement initiatives implemented by the Lao government (Ovesen 2004: 465-9), the forest management efforts (Vuong 2004: 327-9), top-down rural development programmes (Slack 2022: 74), and religious oppression (Ngô 2016) in Vietnam, as well as structural inequality in China (Shi et al. 2019) have all showcased political disputes, ethnic inequalities, economic disparities, and conflicting priorities. Nonetheless, these policies compel the Hmong people to engage in negotiations with various actors and have led to their strategic cross-border migration as a response.

Portrayals of the Hmong people in academic reports on Southeast Asia tend to be polarised. On the one hand, they are often depicted as premodern settlers and isolated individuals, choosing to live in mountainous areas due to a lack of interest in modern politics or an inability to adapt to contemporary society (Scott 2009). This direction puts more attention on “agrarian livelihoods” (Turner, Bonnin, and Michaud 2015) and “dying traditions,” and has created an impression that the Hmong in Southeast Asia are remote figures living off subsistence economies. In previous “uplanders” studies on this region, there was a similar perception of remoteness, as evidenced by the findings of Stolz and Tappe (2021). On the other hand, they are depicted as vulnerable victims of social modernity, as in Wilcox’s (2021: 122-4) observation and Lee’s description (2024) on the Lao Hmong community. Rumsby (2023) also argued that Vietnamese Hmong farmers and precarious workers experienced exploitation within an unequal economic framework and also faced ethnic discrimination in China. Prior studies have often concluded that resourcefulness and agency may not lead to upward mobility in the face of significant economic inequality and ethnic discrimination (Turner, Bonnin, and Michaud 2015; Rumsby 2023). However, considering the extensive duration of these multi-level cooperation programmes such as the GMS and the Belt and Road Initiative between China, Vietnam, and Laos, it is essential to examine whether ethnic locals have truly reaped the benefits and the impact of economic integration, enhanced border access, and proactive policies for the upward mobility of the Hmong community.

To date, several studies have investigated how (in)formal economies provide ethnic minorities such as the Hmong with crucial pathways to shape their life trajectories, cultural development, and economic prosperity (Baird and Vue 2015; Turner, Derks, and Rousseau 2022: 10). Scholars such as Sangmi Lee (2024) have documented the presence of several Chinese Hmong peddlers who have established a settlement in Laos. Rumsby (2023) and Thi, Xuan, and Thi (2024) reported that Vietnamese Hmong are often drawn to China, where they can expect higher wages in precarious job markets. However, few studies have investigated Hmong entrepreneurship in any systematic way, in particular how individuals in this area have developed negotiation strategies and mobility patterns in response to local and global governance.

Research methods

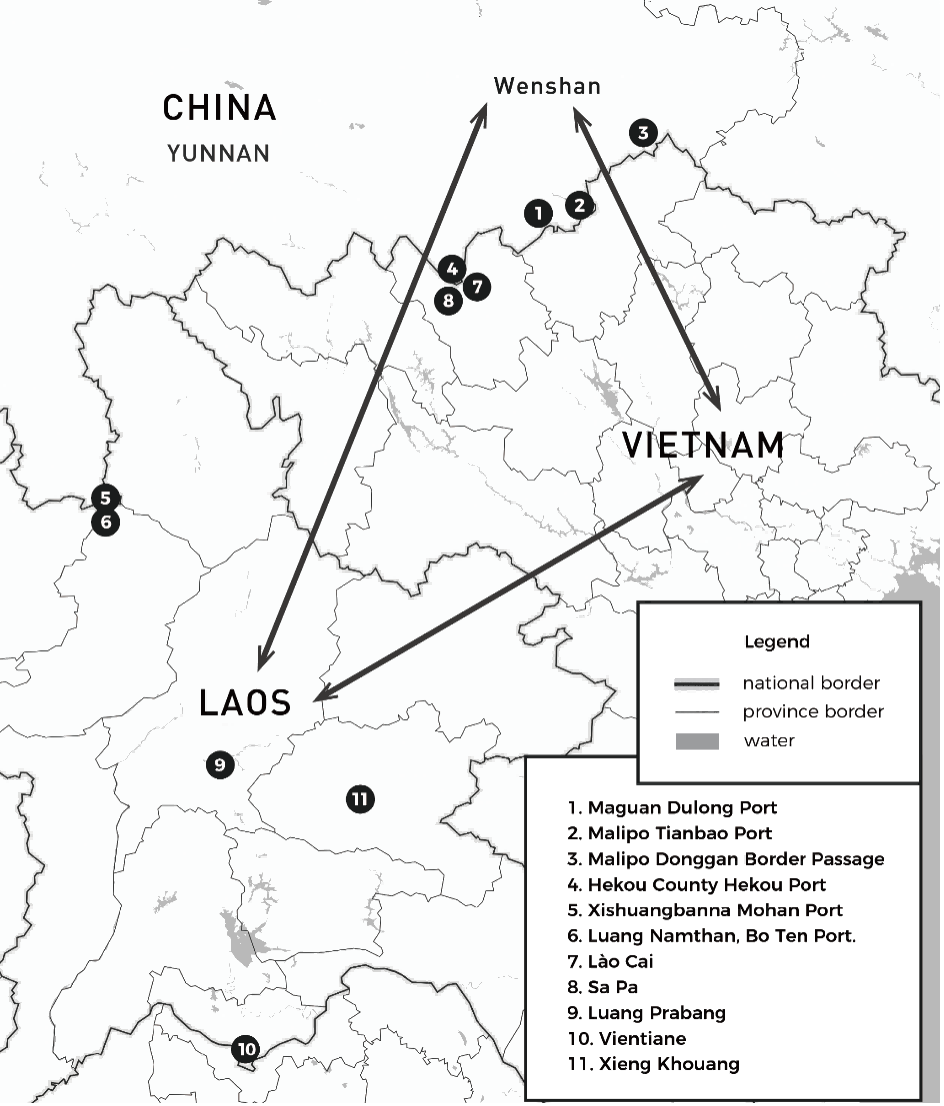

This study employs comprehensive multisite ethnographic fieldwork, detailed in the figure below, to capture the dynamic nature of the Hmong people’s transborder migration across China, Vietnam, and Laos. The primary data for this research was obtained from an extensive long-term field study on the Hmong identity, conducted intensively from September 2015 to February 2016, with supplemental trips through July 2024. This temporal and spatial breadth ensured a collection of rich data through in-depth interviews and participant observations.

Table. Multisite fieldwork in the three countries

| Country | Province | Prefectures | Counties/Ports | Time |

| China | Yunnan | Wenshan | Malipo, Tianbao | 2015, 2024 |

| Malipo, Donggan | 2024 | |||

| Maguan, Dulong | 2024 | |||

| Honghe | Hekou, Hekou | 2012, 2023 | ||

| Xishuangbanna | Mengla, Mohan | 2015, 2016, 2024 | ||

| Vietnam | Lào Cai | Lào Cai | Lào Cai Port | 2015, 2024 |

| Sa Pa | 2015, 2024 | |||

| Laos | Vientiane Municipality City | 2024 | ||

| Xieng Khouang | Phonsavan | 2024 | ||

| Luang Prabang | Luang Prabang City | 2011 | ||

| Luang Namtha | Bo Ten Port | 2011, 2024 | ||

Source: author.

The primary data collection technique employed was snowball sampling, which is particularly effective in hard-to-reach populations. At each site, questions were asked about the knowledge of individuals who migrated into or out of the two countries, focusing on non-farming sectors. This approach addressed a gap in previous Southeast Asian research on the Hmong, which had not thoroughly considered this bidirectional movement.

The snowball sampling method depends on the social networks and recommendations of the participants (Noy 2008). My interlocutors often referred “successful” family members, relatives, and friends for interviews. I encountered rejection from potential interviewees who believed they were not successful enough to share their experiences, or were not high-ranking figures. On one occasion, the elder brother of a potential interlocutor called me, cautioning me about maintaining the reputation of his family, clan, county, and the Chinese Miao community when I attempted to contact his “unsuccessful” younger brother in Laos. Such reaction therefore influenced the framework of this article, prompting me to make sure that his personal accounts would not be scrutinised within this research. Without invalidating this research, this context surely constitutes a limit to take into account as far as data collection is concerned: it participates in successful stories occupying a more central position in this article.

In this article, I analyse data from 47 interviews, including 22 Chinese Hmong, 15 Vietnamese Hmong, and ten Lao Hmong interlocutors. Their journeys include various domestic and international relocations, ranging from Laos to China and Japan, and from Vietnam to Singapore and Thailand, either as tourists, precarious labour, or undocumented migrants. These past experiences significantly influence their entrepreneurial decisions, business preferences, and negotiation approaches.

Given the absence of statistics on Hmong migrants in the three countries, and the fact that Hmong migrants from these countries represent various categories of migration, from marriage mobility to temporary farmworkers, and from student migration to family reunion, their actual number is difficult to assess. In conversations with numerous local Lao Hmong during my fieldwork, I realised that nearly everyone knew at least one or two Chinese Hmong who were involved in selling ethnic clothing in Laos.

The snowball sampling method offers the advantage of being able to cross-check information. Some of the individuals I interviewed are well-known in their “entrepreneur circle,” which provided me with the opportunity to verify certain details by referencing previous conversations. Additionally, I often visited their workplaces, such as stores, hotels, bars, livestream rooms, massage parlours, and offices, in order to form initial impressions, measure business performance, and verify information. I omitted certain stories that I couldn’t fact-check, such as allegations of smuggling and human trafficking. Most interviews took place in restaurants, coffee bars, or quiet corners of parks, and I deliberately refrained from recording in order to preserve the natural flow of our interactions. I compiled keywords and short sentences on my mobile phone and subsequently, following each discussion or observation, I documented our conversation in a reflective diary.

The strategic selection of specific locales for data collection was driven by their unique socioeconomic and cultural significance in the transborder exchanges. On the China-Laos border, Mohan Port (China) and Bo Ten Port (Laos) were selected due to their important roles in facilitating commerce and migration between the two countries. Additionally, on the China-Vietnam border, sites in Wenshan and Honghe prefectures (China) and Sa Pa Town and Lào Cai City (Vietnam) are known for their vibrant border markets and cross-border trade. In Laos, the cities of Luang Prabang, Phonsavan, and Vientiane, all destinations for Hmong transborder migrants, provided unique perspectives on the significant contributions of Laos to the region (see figure below).

Figure. Field sites and trans-mobilities in China, Vietnam, and Laos

Credit: Birun Zou.

During my pilot fieldwork in Wenshan, China, from 2015 to 2016, I established connections within the Hmong community and learned the Hmong language. Despite their self-referring as Hmong, I (from the Xongb subgroup) was quickly embraced as a member, primarily because we are “Miao” in China.[2] Later, my PhD research within the European Hmong community expanded my network across Southeast Asian countries through familial and clan connections. Throughout the study, I conducted interviews primarily in Hmong, occasionally code-switching to English and Chinese based on the preference of my interlocutors.

My educational background and academic position facilitated my engagement with this particular group. My interlocutors have shown an enthusiasm to “assist a fellow Miao/Hmong sister” and to have their stories “officially” documented for broader understanding. Residing in China has facilitated regular visits to my interlocutors, providing me with a unique chronological and logistical advantage. Over the years, I have observed my interlocutors navigate diverse border policies, alter their life trajectories, and adapt their strategies in response to various situations – all of which are central themes in this study.

This study serves as a pioneering exploration into the experiences of Hmong entrepreneurs within the tri-state area. Nonetheless, this trajectory could be further enriched by incorporating perspectives from other disciplines, perspectives, ethnicities, or nationalities, such as the voices of Lao or Vietnamese Hmong scholars, in future research.

Cross-border Hmong migrant labour

Since the reforms in the 1980s, the restrictions on cross-border migration of border residents in the tri-state area have been lifted, largely due to improved cooperation aimed at economic development (Kuah 2000: 76-8). Consequently, the Hmong people in this area have become increasingly mobile and adept at leveraging their social networks for personal gain (Baird and Vue 2015). The agricultural sector, the main livelihood for local people (Ovesen 2004; Vuong 2004), underwent substantial changes (Turner, Bonnin, and Michaud 2015: 44-6; Rumsby 2023) and benefitted from enhanced cross-border mobility.

Thousands of Chinese rural residents – including residents from Yunnan’s border regions – have migrated to urban centres in search of job opportunities (Shi et al. 2019). This mass migration has left the border regions struggling to develop or even sustain their existing industries. The loosening of cross-border migration restrictions emerged as a viable solution that allowed farmers to hire foreign co-ethnic farmworkers (Rumsby and Gorman 2023). For instance, in Malipo County, Hmong workers from Huyện Đồng Văn, Hà Giang, are a common sight in the fields, earning wages of RMB 70-100 a day. These rates are notably higher than the RMB 40-70 a day typically earned in Vietnam. Such wage differentials underscore the economic motivations behind cross-border labour movements.

Rumsby (2023) documented instances of labour exploitation, non-payment of wages, and strenuous labour as part of the Hmong migrant experience in China. However, my interlocutors mainly expressed frustration with bureaucratic hurdles such as foreign resident card applications and homesickness.[3] They did express some level of satisfaction with their living conditions and income, especially when comparing them to working conditions in Vietnam and Laos. In Thi, Xuan, and Thi’s (2024) study of the Sino-Vietnam border, it was found that migrant villagers derived significant earnings from their cross-border labour activities, which enabled them to construct concrete residences designed in the style of Chinese architecture in Vietnam. According to Lyttleton and Li (2017: 305), economic prosperity is evident in the Lao Akha community,[4] who have shown a strong inclination towards seeking material wealth, predominantly through participation in rubber ventures with China.

Border residents noted that a relatively “open border” policy facilitated smoother transitions and less bureaucratic interference in daily crossings:

Before the epidemic, there was no barbed wire fence here, and the Hmong on both sides used to walk right across the border to their villages in Vietnam. When I was younger, in my twenties, I used to go over to Vietnam for a month or so. I used to haul cattle and pigs here from Vietnam. (Interview with a Chinese Hmong male in his fifties, farmer in Yunnan and migrant worker in Guangdong, February 2024)

In addition to enhancing agricultural productivity, the loosening border policy before Covid-19 significantly supported growth in other previously underdeveloped and labour-intensive sectors, such as tourism, which has seen a notable increase. For example, having previously worked in Vientiane as a tourist guide without a work permit, Mei, a Vietnamese Hmong, led international tourists, predominantly Europeans and Koreans, on tours to Lao Hmong villages. Due to mutual visa exemption agreements, Mei was not required to apply for a tourist visa and could stay for up to 30 days at a time. This flexibility in border policies significantly benefitted the Hmong and other minority groups, enabling them to engage in tourism and other economic activities across borders.

This era of relatively free migration prior to the pandemic was characterised by significant administrative adjustments. Since the 1990s, the Chinese government, for instance, simplified visa and customs procedures and allowed for daily reentries, streamlining cross-border movement considerably. In Vietnam, the Lào Cai provincial government took proactive steps to attract cross-border trade and investment by implementing tax-free zones and rolling out ambitious capital expansion plans in the first decade of the twenty-first century[5] (Chan 2013). Due to the loosening border control, border residents often worked in precarious jobs without permits or travel documents (Molland 2017: 345). Being undocumented puts them in a vulnerable position when dealing with the authorities. The increasingly stringent enforcement of policies against illegal immigration, residency, and employment in China has raised concerns about the potential for detention and deportation.

The importance of infrastructure development in borderlands and proactive border policies, as emphasised by Saxer, Rippa, and Horstmann (2018: 4), lies in its ability to integrate peripheries into states and facilitate cross-border trade while strengthening biopolitical interventions and exercising control. In regions such as the previously war-torn tri-state area, states often manage cross-border migrations carefully to control the flow of goods and cultural exchanges, regulate labour markets, and maintain territorial integrity (Kuah 2000; Chan 2013; Colin 2014; Rowedder 2022). For instance, the Lao government focuses on managing the “crypto-separatism” of ethnic minorities (Wilcox 2021: 95-8), while the Vietnamese government is concerned with monitoring the activities of the Christian Hmong community (Ngô 2016; Rumsby 2024) and the Chinese government preoccupied by the interference from Overseas Hmong community. Consequently, ethnic locals’ movements are closely monitored and sometimes restricted to ensure that their migrations and their employment align with the developmental and security priorities of these states. However, the tri-state area has an increasing demand for labour in a variety of sectors, while the Hmong leverage their familial and linguistic skills to achieve personal advantages.

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on people living on both sides of the border, particularly due to the imposing fences that remain along China’s border. According to Sarah Turner (2022: 220), trade between China and Vietnam has decreased and border controls have become stricter, affecting farmers and smaller-scale traders who previously used informal crossing points. Similarly, Thi, Xuan, and Thi (2024) reported that the barbed-wire fence has raised awareness among Vietnamese ethnic minorities about the border due to its impact on economic mobility. As per the latest regulation, border residents are mandated to obtain a border resident card in order to visit their siblings and relatives. This requirement has added further ambiguity concerning future visitations and has led to changes in the daily routines and family plans of ethnic residents.

Cross-border Hmong middleman entrepreneurship

Despite of the pandemic, the sustained economic development of the tri-state area has created new opportunities in emerging industries, such as tourism, wholesale, hospitality, and cosmetics industry, for those with entrepreneurial aspirations (Wilcox 2021: 40-1). A considerable influx of Chinese investors and businesspersons in the tri-state area enhances the flow of goods and services across borders and bolsters economic ties (Nyíri and Tan 2017: 7). Often, the Hmong people serve as a pivotal “middleman minority,” effectively bridging the gap between businesspersons from inland China, who possess substantial financial capital, and local ethnic minorities, whose communities are rich in natural resources. This unique position allows them to facilitate transactions and collaborations that leverage the strengths of both groups, promoting mutual economic growth and integration within the region.

For example, in Xieng Khouang, Chinese Hmong capitalised on the “mine rush,” not by mining but by managing hotels that catered to the influx of Han Chinese[6] mining entrepreneurs in Laos. These Chinese entrepreneurs were drawn to the local Lao Hmong communities by the allure of potential gold and copper mine sites. As one of the hotel managers noted, their role allowed them to profit from the booming mining industry while providing essential services:

Our rooms are full recently and all [Han Chinese] customers are mining entrepreneurs, no matter whether gold or copper mining. I just went to the airport to pick up a bunch of mining entrepreneurs. (Interview with a Chinese Hmong, March 2024)

In addition to profiting from Han Chinese businesspersons, Hmong entrepreneurs often acquire skills from them and later adapt these skills for their own ventures. Mr Tzu, a Chinese Hmong in his fifties, exemplifies this learning and adaptation process. He owns a tea company in Malipo County, where, starting in 2000, Fujian brokers began purchasing black tea and Pu’er tea. At the beginning, he lost a lot of money due to wrong judgements on the tea market and low production quality. These intermediaries brought in tea technicians from Fujian and Taiwan who taught Mr Tzu the intricacies of producing high-quality black tea. Building on this knowledge, in 2015, Mr Tzu travelled to Tỉnh Hà Giang in Vietnam to locate ancient tea trees. He returned the following year to hire Vietnamese Hmong and Yao individuals through local Hmong connections to harvest the tea leaves. This attention to detail in sourcing and production allowed Mr Tzu to command prices ranging from approximately RMB 40 per gram for purchasing raw materials to about RMB 3,000 per gram (depending on the market) when selling the finished product. This case exemplifies the intertwined functioning of networks, knowledge-transfer, and business management strategies operated by cross-border Hmong middleman entrepreneurship.

In their pursuit of business success, the Hmong people effectively utilise their clan system to find co-ethnic partners and workers, streamline communications, and ensure trust and cooperation. For instance, Mr La, a Chinese Hmong, along with his friends, initiated a hotel venture in Xieng Khouang, Laos, in 2023. Mr La had previously cultivated relationships with some Lao Hmong friends during his university days in Kunming. These connections proved important when, after several exploratory trips to Laos, they decided to open a hotel. They hired five Lao Hmong women as room service workers and a Lao Hmong man as the receptionist. Importantly, one of the shareholders, who is also Lao Hmong, brought invaluable experience that facilitated the negotiation processes with the Lao government, fire department, police, and other organisations. When facing bribery or unclear penalties, they usually chose to pay the fees but let the Lao Hmong deal with them. This strategic use of familial and ethnic ties and linguistic capital not only facilitated the establishment of their business but also integrated it smoothly into the local community.

Linguistic capacities are important in developing transnational cooperation among these transborder entrepreneurs. Chinese Hmong entrepreneurs, active in diverse industries including wholesale clothing, agarwood trading, casinos, and tourism, leverage their linguistic skills and cultural insights to establish unique niches within these sectors. For instance, Mr Liu, a Chinese Hmong, operates a small startup that manages the China-Vietnam import and export business. Mr Liu hired Vietnamese Hmong women to promote a variety of products in the Vietnamese, Hmong, and Chinese languages through platforms such as TikTok, Facebook, and Shopee. His company shows how deep language proficiency and an understanding of cross-cultural dynamics are critical in navigating the complex landscapes of international trade. In the first eight months, Mr Liu lost approximate RMB 400,000, but profit and loss have balanced more recently. According to him:

Vietnam Hmong make hemp cloth, but Vietnam manufacturing isn’t good; there is no machine to make the dress. We imported hemp cloth after the addition of Hmong embroidery and sold it to the ethnic markets in China and Vietnam. We also exported Chinese products to Vietnam, including daily necessities, and Vietnam Hmong imported goods of all kinds. For example, a pair of shoes has a RMB 10 wholesale price, but in Vietnam, they sell for more than RMB 30. Recently, we sold glyphosate, dozens of tons, exported to Vietnam. (February 2024)

These cases demonstrate the bridging strategy that the Hmong entrepreneurs have developed to leverage their linguistic skills in effectively navigating complex circumstances. This approach involves exchanging information about their professions and cultural backgrounds when they meet, often in multiple languages to ensure clarity and accuracy. For instance, during a dinner between two Chinese Hmong and three Lao Hmong, conversations flowed seamlessly between Laotian, Hmong, Chinese, and English, covering topics from mobile data deals to job applications in Laos. This multilingual capability also supports deeper integration into various business settings. Mai, a Lao Hmong and ethnic clothing retailer, collaborates with Chinese Hmong partners to import materials from China and assemble them in Laos, converting linguistic fluency into economic opportunities. This “Hmong connectedness” further serves as a protective layer that enables cross-border Hmong individuals to navigate and mitigate structural disadvantages and bureaucratic challenges. This was demonstrated when Sun, a Chinese Hmong confronted by Lao police for a bribe, used his ethnic identity to avoid the issue. During the visa renewal process, Sun asked an officer whether he was Hmong or not. Sun spoke in Hmong, “I’m Hmong too,” upon receiving an affirmative response. Subsequently, Sun bypassed the waiting line and bribe and proceeded to submit his application materials.

Mr Thao’s business stands out as one of the most significant entrepreneurs in this study. In 1991, Mr Thao left his home village of Wenshan, China, to venture into the rubber industry in Xishuangbanna. Later, he relocated to Laos with Lao Hmong returnees and was naturalised in 1995. Mr Thao planted rubber trees on approximately two hectares of land and began harvesting latex in 2000. By selling the latex to Chinese, Mr Thao achieved his initial success. Subsequently, he diversified his investments, transitioning away from plantations. By 2018, he had invested in a hotel, leased a warehouse, acquired more than 20 container trucks, and even established a gas station.

Reflecting on his past experiences, Mr Thao recognised his ability to adapt quickly to capture niche markets, especially during the time when Laotians were hesitant to engage in rubber tree plantation. Leveraging his familial and linguistic skills, Mr Thao collaborated with Chinese companies and the Lao government, and successfully negotiated with local authorities. Although there were concerns from local residents about the potential environmental impact of his gas station, Mr Thao persuaded the local government and secured official approval for the continued operation of his gas station. Apart from local governance issues, Mr Thao also expressed dissatisfaction with tariffs, given that he exported his latex to China. In summary, Mr Thao credited his success to his adaptability in seizing opportunities as a mediator between China and Laos. This “middleman minority” trend has also been observed among the Lao Akha as they pursued economic prosperity through rubber ventures with the Chinese (Lyttleton and Li 2017).

The literature on middleman minorities indicates that specific minority groups were incentivised to engage in businesses catering to other minority populations, consequently cultivating varying degrees of economic influence (Min 2017). South-South cooperation offers the framework and opportunities (Sisouphanthong 2014) for ethnic minorities to carve out sustainable livelihoods (Rowedder 2022). In the cross-border Hmong cases, fluency in multiple languages allows Hmong individuals to bridge cultural and communication gaps, tap into diverse markets, expand their customer base, broaden access to cross-border social networks, and gain a competitive edge in global markets. Their connectedness resonated in the literature on the vital role of migration networks in integration and upward social mobility (Zhou 2004; Phouxay 2017: 363; Liang 2023).

Cross-border Hmong enclave entrepreneurship

Ethnic enclave entrepreneurship serves as a platform for the Hmong to leverage ethnic and cultural bonds to create economic opportunities (Schein 2004). Entrepreneurs within these enclaves often capitalise on shared language, traditions, and social norms to facilitate business operations and customer relations (Baird and Vue 2015; Rumsby and Gorman 2023). This model sustains economic growth within the enclave, enhances the socioeconomic status of its members, and benefits the broader community (Zhou 2004; Liang 2023).

Cross-border Hmong enclave entrepreneurship is dominated by the ethnic clothing, tourism, and leisure industries, which are considered the top three sectors in this particular economic context. Lily, a Chinese Hmong in her late twenties, first travelled to Xieng Khouang in 2019 as a microentrepreneur, selecting fashionable Lao Hmong attire to sell on the platform Kuaishou, where she earned RMB 400 to 500 per dress. Since the latest Hmong diaspora in the 1970s, ethnic clothing has become a significant segment of the global Hmong market (Shi 2023). Turner, Bonnin, and Michaud (2015: 127) noted that some Vietnamese Hmong were wearing factory-made Hmong clothes imported from China, underscoring the transnational flow of these goods. Lily observed that as the business flourished, an increasing number of Lao Hmong started to participate, which led to a reduction in prices. Although profits have not grown substantially, some Chinese Hmong entrepreneurs continue to operate in this sector in Laos.

The ethnic tourism industry has also provided a lucrative opportunity for Hmong entrepreneurs to capitalise on their ethnic heritage. Ethnic tourism gained popularity in the 1990s when Hmong from America and Europe were drawn to visit their ancestral homelands in China or Laos (Tapp 2003; Schein 2004; Schein and Vang 2021; Shi 2023; Lee 2024). The nature of this business has evolved, with Chinese Hmong/Miao now increasingly seeking to connect with their “Hmong/Miao brothers and sisters” across Southeast Asian countries. Sun, a Chinese Hmong in his forties, pivoted to the tourism sector in 2015 after his bar in Ban KM 52, Vientiane Province, closed due to poor management. Sun now operates two tourist routes: one for Chinese Hmong/Miao visiting Laos and Vietnam, and another for Overseas Hmong exploring Hmong/Miao villages in China. Fluent in Hmong and familiar with Laotian, Sun adapts his language use in his business – speaking Hmong with American and Chinese Hmong tourists, Laotian to Lao officials, and hiring a Vietnamese Hmong guide for trips to Vietnam to facilitate negotiations with Vietnamese. Sun’s sophisticated management of these tours, earning over RMB 10,000 per trip and handling at least two tourist groups per month, underscores the vibrant potential of ethnic tourism in the Hmong community.

Ethnic performances also significantly contribute to the Hmong market, especially during the Noj Peb Caug (Hmong New Year) Festival, which attracts Hmong artists from various countries. While statistics are scarce on the invitation of Overseas Hmong singers to China, these artists have developed a substantial fanbase and earn considerable sums. During the 2024 festivals across border regions, Lao Hmong rappers, Vietnamese Hmong singers, and American Hmong vocalists were prominent. Due to the substantial economic returns, Minyun, a Vietnamese Hmong from Lào Cai, and her band have embarked on performance tours across several Chinese counties. Their payment depends on negotiations and fame, ranging from RMB 5,000 to 20,000. Nana, a Chinese Hmong entertainment broker, explained the dynamics of the industry:

Minyun and Lulu are very hot in the Vietnamese Hmong community; they have been live-streamed on Kuaishou for a long time, so many Hmong people on our side know them. (...) We are close to Laos and Vietnam, so we often listen to Laotian and Vietnamese Hmong music, and I can tell their nationalities as soon as I hear it. (February 2024)

The booming Hmong entertainment market has significantly influenced Hmong-themed bars. In the cities of Mengzi and Wenshan in China, I visited three such establishments, each rooted in Hmong culture – from decorations featuring traditional flute pipes and Hmong script to interiors adorned with patterns and icons of Hmong attire. The staff are Hmong – from owners to bartenders and entertainers – ensuring streamline communication with their Hmong clientele. They also host performances by popular Hmong artists from other countries, such as Lim from Vietnam, who gained popularity on Kuaishou. Despite visa restrictions limiting his stay, Lim’s business engagements are facilitated by his Chinese Hmong friends, who ensure he is well-informed and comfortable in his interactions without needing to speak Chinese.

The rise of online entertainment and commerce has opened new avenues for co-ethnic engagement within the Hmong community. Mr Feng, initially a hotel manager in Luang Prabang, until 2022 due to the Covid-19 impacts, pivoted to using livestream platforms such as Kuaishou and TikTok to showcase Lao Hmong girls dancing, tapping into the burgeoning online ethnic entertainment market. In 2023, livestreamed “dancing” performances were curtailed by the Lao government, which claimed that such performances were detrimental to the reputation of the country. Mr Feng then relocated to Mohan Port and continued his livestreaming ventures there. Similarly, in China’s Wenshan City and Guannan County, several Vietnamese Hmong women have embraced this digital shift, using livestreaming to sell skincare products and traditional Hmong attire. This integration of traditional business with modern digital strategies shows how Hmong migrants navigate the challenges and opportunities of the digital economy.

The dynamics of international relations significantly impact cross-border cooperation within ethnic enclave entrepreneurship. The implementation of barbed-wire fences has compelled them to utilise dry ports, consequently increasing their costs. Simultaneously, prevailing stereotypes have been perpetuated through increasingly frequent interactions and collaborations. Chinese Hmong individuals have expressed dissatisfaction with their co-ethnic workers as “slow-paced,” “not working hard,” and having “no concept of saving money.” This tension has also been noted by Sangmi Lee (2024) between American Hmong and Lao Hmong communities, highlighting the discourse of national stereotypes and competition among diasporic groups.

To summarise, the emergence of the Hmong market – a marketplace created by and for the Hmong – has been marked by both the traditional handicraft and light industrial sectors, and innovative ventures into the leisure industry, ethnic consumption, and new media. According to Zhou’s research (2004), enclave entrepreneurs are recommended to play a role in facilitating transactions and communication across diverse communities, potentially leading to economic success. Liang’s research (2023) on Chinese restaurants in New York City provided evidence of the significant potential for upward mobility based on ethnic enclaves. The activities of entrepreneurs in cross-border Hmong enclaves foster community cohesion and identify lucrative business opportunities both within the Hmong community and in broader markets.

Conclusion

This study has explored the complex interplay of local and global governance frameworks, highlighting the dynamic nature of transborder mobility and the strategies the Hmong employ to navigate these shifts. The historical context of the Hmong people, originating in the highland territories across China, Vietnam, and Laos (Michaud 1997), sets the stage for understanding their current socioeconomic transformations. Historically marginalised and often governed by policies that restrict their movement and economic opportunities (Ovesen 2004; Vuong 2004; Slack 2022), the Hmong have developed resilient strategies to overcome these challenges and underscore their ability to capitalise on the new opportunities offered by cross-border interactions.

Since the twenty-first century, there has been a noticeable increase in the prominence and involvement of Southern partners as influential actors in centred partnerships aimed at mutual benefit, economic growth, and regional development (Mawdsley 2024: 207). Significant to this adaptation is the role of South-South cooperation, which has become increasingly vital for regional integration and economic development in Southeast Asia (Nyíri and Tan 2017: 9-11; Engel 2019). This form of cooperation has provided the Hmong and other ethnic minorities with new avenues to advance economically and socially. The enhanced cross-border mobility among the Hmong people was a result of their ethnic culture and kinship systems, aligned with the adjustment of border policies and trilateral South-South cooperation. Migrant entrepreneurs navigated niche markets through middleman and enclave entrepreneurship, negotiating with a wide range of actors and traversing different paths to achieve economic integration and upward mobility. Furthermore, they diversify their investments and business ventures, such as operating a hotel in conjunction with an automobile sale shop, working as an entertainment broker while selling imported ethnic attire online, pursuing a career as a singer while selling imported skincare products online, and more. The cases highlighted in this article illustrate the intricate interplay of traditional culture, cross-border markets, governance structures, and international cooperation, as well as individual attributes, strategies, and agency.

This study reveals that the Hmong have leveraged their cultural and linguistic capital to forge substantial networks across borders. These networks are not just platforms for economic exchange but also serve as conduits for cultural and social exchange, strengthening ties between Hmong communities in different countries and enhancing their collective bargaining power and market presence. However, in contrast to the ethnic discrimination frequently experienced by the Hmong population in their domestic society, migrant Hmong entrepreneurs often encounter challenges related to international relations and immigration policies. For example, Chinese Hmong individuals frequently encounter issues related to “bribery” in Laos and Vietnam due to their citizenship and perceived wealth, while Hmong from Laos and Vietnam are concerned about their undocumented status in China due to stricter immigration policies.

By situating the lives of the “upland pioneers” (Stolz and Tappe 2021) within the broader context of South-South cooperation, this study provides a deeper insight into the mechanisms through which local communities can leverage external forces and their own agency to build prosperous futures, from the perspective of some of their most successful members. But it’s crucial to recognise the potential risks associated with frequently entering into long-term business management without adequate protections in place. Hmong middleman entrepreneurship and enclave entrepreneurship are particularly vulnerable, as these industries rely on local governance, international cooperation, and the global market. The Hmong entrepreneurs in this study emphasised that these factors significantly influenced their decision-making processes and entrepreneurial strategies. The increased infrastructure development in this tri-state area, while initially facilitating the cross-border migration and economic activities of the Hmong people, will inevitably attract larger-scale migration and economic activities from ethnic majorities in the three countries and even far beyond. Such a shift is very likely to exacerbate the future economic and livelihood vulnerabilities of the Hmong in this region, as they may face greater competition for resources and opportunities.

Acknowledgements

The map of the field sites was skilfully drawn by Birun Zou. I am deeply grateful for all the support and assistance provided during the fieldwork. During the preparation of this work I used The Grammarly-AI assistant in order to improve readability and language. After using this tool/service, I reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication. Some ethnographic data was presented at the Tenth Youth Forum of Anthropology in China at the Southeast University (Nanjing) in 2024, and the Regional Conference of AAS-in-Asia in 2024 at the Universitas of Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. I want to express my gratitude to the reviewers for their constructive and insightful suggestions that have significantly improved the quality of the manuscript.

The work was supported by the Zhejiang Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences Circles [Grant number: 24LMJX03YB].

Manuscript received on 10 June 2024. Accepted on 23 September 2024.

References

BAIRD, Ian G., and Pao VUE. 2015. “The Ties That Bind: The Role of Hmong Social Networks in Developing Small-scale Rubber Cultivation in Laos.” Mobilities 12(1): 136-54.

BRY, Sandra H. 2017. “The Evolution of South-South Development Cooperation: Guiding Principles and Approaches.” The European Journal of Development Research 29: 160-75.

CHAN, Yuk Wah. 2013. Vietnamese-Chinese Relationships at the Borderlands. London: Routledge.

CHATURVEDI, Sachin. 2017. “The Development Compact: A Theoretical Construct for South-South Cooperation.” International Studies 53(1): 15-43.

COLIN, Sébastien. 2014. “The Participation of Yunnan Province in the GMS: Chinese Strategies and Impacts on Border cities.” In Nathalie FAU, Sirivanh KHONTHAPANE, and Christian TAILLARD (eds.), Transnational Dynamics in Southeast Asia: The Greater Mekong Subregion and Malacca Straits Economic Corridors. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 107-42.

CULAS, Christian, and Jean MICHAUD. 2004. “A Contribution to the Study of Hmong (Miao) Migrations and History.” In Nicholas TAPP, Jean MICHAUD, Christian CULAS, and Gary Yia LEE (eds.), Hmong/Miao in Asia. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. 61-96.

ENGEL, Susan. 2019. “South-South Cooperation in Southeast Asia: From Bandung and Solidarity to Norms and Rivalry.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 38(2): 218-42.

FORSYTH, Tim, and Jean MICHAUD. 2011. “Rethinking the Relationships between Livelihoods and Ethnicity in Highland China, Vietnam, and Laos.” In Jean MICHAUD, and Tim FORSYTH (eds.), Moving Mountains: Ethnicity and Livelihoods in Highland China, Vietnam, and Laos. Vancouver: UBC Press. 1-27.

GRAY, Kevin, and Barry K. GILLS. 2016. “South-South Cooperation and the Rise of the Global South.” Third World Quarterly 37(4): 557-74.

KUAH, Khun Eng. 2000. “Negotiating Central, Provincial, and County Policies: Border Trading in South China.” In Grant EVANS, Christopher HUTTON, and Khun Eng KUAH (eds.), Where China Meets Southeast Asia: Social and Cultural Change in the Border Region. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 72-97.

LEE, Sangmi. 2024. Reclaiming Diasporic Identity: Transnational Continuity and National Fragmentation in the Hmong. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

LIANG, Zai. 2023. From Chinatown to Every Town: How Chinese Immigrants Have Expanded the Restaurant Business in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press.

LIGHT, Ivan, and Steven GOLD. 2000. Ethnic Economies. Cambridge: Academic Press.

LYTTLETON, Chris, and Yunxia LI. 2017. “Rubber’s Affective Economies: Seeding a Social Landscape in Northwest Laos.” In Vanina BOUTÉ, and Vatthana PHOLSENA (eds.), Changing Lives in Laos: Society, Politics, and Culture in a Post-socialist State. Singapore: NUS Press. 301-24.

MAWDSLEY, Emma. 2024. “South-South Cooperation and Decoloniality.” In Henning MELBER, Uma Kothari, Laura CAMFIELD, and Kees Biekart (eds.), Challenging Global Development. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 205-14.

MELLAC, Marie. 2014. “Vietnam, an Opening under Control, Lào Cai on the Kunming-Haiphong Economic Corridor.” In Nathalie FAU, Sirivanh KHONTHAPANE, and Christian TAILLARD (eds.), Transnational Dynamics in Southeast Asia: The Greater Mekong Subregion and Malacca Straits Economic Corridors. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 143-74.

MICHAUD, Jean. 1997. “From Southwest China into upper Indochina: An Overview of Hmong (Miao) Migrations.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 38(2): 119-30.

——. “Handling Mountain Minorities in China, Vietnam and Laos: From History to Current Concerns.” Asian Ethnicity 10(1): 25-49.

MICHAUD, Jean, and Christian CULAS. 2000. “The Hmong of the Southeast Asia Massif: Their Recent History of Migration.” In Grant EVANS, Christopher HUTTON, and Khun Eng KUAH (eds.), Where China Meets Southeast Asia: Social and Cultural Change in the Border Region. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 98-121.

MICHAUD, Jean, and Tim FORSYTH (eds.). 2011. Moving Mountains: Ethnicity and Livelihoods in Highland China, Vietnam, and Laos. Vancouver: UBC Press.

MIN, Pyong Gap. 2017. “Middleman Minorities.” In George RITZER (ed.), The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. New York: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosm099.pub2

MOLLAND, Sverre. 2017. “Migration and Mobility in Laos.” In Vanina BOUTÉ, and Vatthana PHOLSENA (eds.), Changing Lives in Laos: Society, Politics, and Culture in a Post-socialist State. Singapore: NUS Press. 327-49.

Ngô, Tâm T. T. 2016. The New Way: Protestantism and the Hmong in Vietnam. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

NOY, Chaim. 2008. “Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 11(4): 327-44.

Nyíri, Pál, and Danielle TAN. 2017. “China’s ‘Rise’ in Southeast Asia from a Bottom-up Perspective.” In Pál Nyíri, and Danielle TAN (eds.), Chinese Encounters in Southeast Asia: How People, Money, and Ideas from China Are Changing a Region. Seattle: University of Washington Press. 3-22.

OVESEN, Jan. 2004. “The Hmong and Development in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic.” In Nicholas TAPP, Jean MICHAUD, Christian CULAS, and Gary Yia LEE (eds.), Hmong/Miao in Asia. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. 457-74.

PETCHARAMESREE, Sriprapha, and Mark P. CAPALDI. 2023. Migration in Southeast Asia: IMISCOE Regional Reader. Cham: Springer.

PHOUXAY Kabmaivanh. 2017. “Patterns and Consequences of Undocumented Migration from Lao PDR to Thailand.” In Vanina BOUTÉ, and Vatthana PHOLSENA (eds.), Changing Lives in Laos: Society, Politics, and Culture in a Post-socialist State. Singapore: NUS Press. 350-73.

QIAN, Junxi, Xihao YANG, and Xueqiong TANG. 2023. “Thinking through the Everywhereness of Borders: Mobile Borders, Everyday Practices, and State Logics in Southwest China.” Eurasian Geography and Economics. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2023.2211594

REEVES, Madeleine. 2014. Border Work: Spatial Lives of the State in Rural Central Asia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

ROWEDDER, Simon. 2022. Cross-border Traders in Northern Laos: Mastering Smallness. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

RUMSBY, Seb. 2023. Development in Spirit: Religious Transformation and Everyday Politics in Vietnam’s Highlands. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

——. 2024. “‘Freedom within the Framework’? The Everyday Politics of Religion, State Repression and Migration in Vietnam’s Borderlands and Beyond.” Religion, State & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637494.2024.2353950

RUMSBY, Seb, and Timothy GORMAN. 2023. “Alternative Development Trajectories? A Quantitative Analysis of Religion as a Vector of Mobility and Education among the Hmong in Upland Vietnam.” Journal of Rural Studies 101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2023.103057

SAXER, Martin, Alessandro RIPPA, and Alexander HORSTMANN. 2018. “Asian Borderlands in a Global Perspective.” In Alexander HORSTMANN, Martin SAXER, and Alessandro RIPPA (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Asian Borderlands. London: Routledge. 1-13.

SCHEIN, Louisa. 2004. “Homeland and Beauty: Transnational Longing and Hmong American Videos.” The Journal of Asian Studies 63(2): 433-63.

SCHEIN, Louisa, and Chia Youyee VANG. 2021. “From Hmong versus Miao to the Making of Transnational Hmong/Miao Solidarity.” In Frank N. PIEKE, and Koichi Iwabuchi (eds.), Global East Asia: Into the Twenty-first Century. Oakland: University of California Press. 219-32.

SCOTT, James. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

SHI, Tian. 2023. “Local Fashion, Global Imagination: Agency, Identity, and Aspiration in the Diasporic Hmong Community.” Journal of Material Culture 28(2): 175-98.

SHI, Tian, Xiaohua WU, Debin WANG, and Yan LEI. 2019. “The Miao in China: A Review of the Developments and Achievements over Seventy Years.” Hmong Studies Journal 20: 1-23.

SISOUPHANTHONG, Bounthavy. 2014. “Integration of Greater Mekong Subregion Corridors Within Lao Planning, on National and Regional Scales: A New Challenge.” In Nathalie FAU, Sirivanh KHONTHAPANE, and Christian TAILLARD (eds.), Transnational Dynamics in Southeast Asia: The Greater Mekong Subregion and Malacca Straits Economic Corridors. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 175-90.

SLACK, Patrick. 2022. “Cardamom Cultivator Concerns and State Missteps in Vietnam’s Northern Uplands.” In Sarah TURNER, Annuska DERKS, and Jean-François ROUSSEAU (eds.), Fragrant Frontier: Global Spice Entanglements from the Sino-Vietnamese Uplands. Copenhagen: NIAS Press. 68-93.

STOLZ, Rosalie, and Oliver TAPPE. 2021. “Upland Pioneers: An Introduction.” Social Anthropology 29: 635-50.

TAPP, Nicholas. 2003. “Exiles and Reunion: Nostalgia among Overseas Hmong (Miao).” In Charles STAFFORD (ed.), Living with Separation in China: Anthropological Accounts. London: Routledge. 157-76.

THI, Thanh Bình Nguyen, Tinh Vuong XUAN, and Mui Le THI. 2024. “Where National Identity Is Contested: Consciousness of Nation-state among Minority Communities in the Vietnam-China Borderlands.” Asian Ethnicity 25(1): 82-103.

TURNER, Sarah. 2018. “‘Run and Hide When You See the Police’: Livelihood Diversification and the Politics of the Street Economy in Vietnam’s Northern Uplands.” In Kirsten W. ENDRES, and Ann Marie Leshkowich (eds.), Traders in Motion: Identities and Contestations in the Vietnamese Marketplace. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 41-53.

——. 2022. “Afterword: Contemplating the Initial Impacts of Covid-19.” In Sarah TURNER, Annuska DERKS, and Jean-François ROUSSEAU (eds.), Fragrant Frontier: Global Spice Entanglements from the Sino-Vietnamese Uplands. Copenhagen: NIAS Press. 219-21.

TURNER, Sarah, Christine BONNIN, and Jean MICHAUD. 2015. Frontier Livelihoods: Hmong in the Sino-Vietnamese Borderlands. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

TURNER, Sarah, Annuska DERKS, and Jean-François ROUSSEAU. 2022. “The Fragrant Frontier: Conceptual and Contextual Introductions.” In Sarah TURNER, Annuska DERKS, and Jean-François ROUSSEAU (eds.), Fragrant Frontier: Global Spice Entanglements from the Sino-Vietnamese Uplands. Copenhagen: NIAS Press. 1-42.

VUONG, Duy Quang. 2004. “The Hmong and Forest Management in Northern Vietnam’s Mountainous Areas.” In Nicholas TAPP, Jean MICHAUD, Christian CULAS, and Gary Yia LEE (eds.), Hmong/Miao in Asia. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. 321-31.

WILCOX, Phill. 2021. Heritage and the Making of Political Legitimacy in Laos: The Past and Present of the Lao Nation. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

ZHOU, Min. 2004. “Revisiting Ethnic Entrepreneurship: Convergencies, Controversies, and Conceptual Advancements.” International Migration Review 38(3): 1040-74.

[1] In July 2009, President Hu Jintao put forward the idea of developing Yunnan Province as a vital gateway for China’s connection to the southwest during his visit to Yunnan. The National Development and Reform Council of China has initiated the development of guidelines, signalling that this strategy has been officially elevated to the national strategic level.

[2] The ongoing debate surrounding the terminology “Hmong/Miao and Hmong vs Miao” is not the primary focus of this article. For a recent summary on this issue, see the work of Schein and Vang (2021). In my present study, the political subcategory of ethnic citizens in the three countries does not hinder the interaction and connectedness of my interlocutors. As numerous previous studies have shown, Hmong people commonly ask each other the same question upon first meeting: “Koj puas yog Hmoob? (Are you Hmong?).” If confirmed, they proceed to establish connections by inquiring about clans and age (Lee 2024), not about the Miao/Hmong issue.

[3] Such conversations were partly attributed to my citizenship, gender, and ethnicity.

[4] Akha is an ethnic group in the tri-state area, known under the name of “Hani” in China.

[5] People’s Committee of Lào Cai Province, 2002, Lào Cai: Potentials for Cooperation and Development, Lào Cai.

[6] In the course of my fieldwork, the majority of mining entrepreneurs I engaged with were of Han Chinese descent, with only a small representation of Dai/Tai and other ethnicities. Aspects of the mining industry are not the primary focus of this article. However, it is important to consider that mining incurs significant environmental destruction and contributes to what some scholars describe as “exploitative” development, a topic that has been thoroughly examined in academic literature.