BOOK REVIEWS

Negotiating Territorial Restructuring in Chinese Borderland Margins: The Viewpoints of Residents of Nujiang, Yunnan

David Juilien is Lecturer in geography at the University of Angers, 10 bd. Victor Beaussier, 49000 Angers, France (djuilien@protonmail.com).

Introduction

Located in the Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture, in the far northwestern corner of Yunnan Province, wedged between Tibet and Myanmar, the Nujiang River Valley (hereafter “Nujiang”) is predominantly inhabited by ethnic minorities living in national margins, such as the Lisu, Nu, Dulong, and Tibetans. The valley has long been identified by the state as one of the many western border regions where local economic systems and spatial organisations are deemed “lagging-behind” (luohou 落後) and in need of economic development and restructuring (Donaldson 2007; Brown and Xu 2010). For decades, Nujiang has been one of the most economically challenged areas of Yunnan. The central government included its counties within western Yunnan’s concentrated and contiguous poverty area (jizhong lianpian tekun diqu 集中連片特困地區), as they combine multidimensional poverty issues stemming from mountainous, ethnic, and rural borderland characteristics that are common throughout the province, and in southwestern China generally (Liu, Liu, and Zhou 2017; Liu S. 2023).

In 2014, the targeted poverty alleviation policy (jingzhun fupin 精准扶貧), a nationwide campaign-style mobilisation of the bureaucracy, was launched to resolve deep poverty issues before 2020, with great pressure on local officials (Zeng 2019). But the campaign also swiftly brought broad spatial changes. In Nujiang, concrete bridges replaced steel ziplines used to cross the river. The main and often bottlenecked highway of the valley, now named “Nujiang Beautiful Highway” (Nujiang meili gonglu 怒江美麗公路), was broadened in 2019 and adorned with flowers to support mass tourism-based development strategies. Meanwhile, environmental policies reshape the landscape with the reallocation of land used to cultivate steep-sloped agriculture. In short, poverty alleviation through development policies is reshaping daily life through Nujiang’s territorial restructuring. This process, initiated by national and provincial government actors, raises questions about potential gaps between government policies and local conditions, about possible resident reactions in the valley, and about attempts to renegotiate top-down policies to better suit local needs and perceptions.

This study explores the possibility for the negotiation of such restructuring through the organisation of protests by “common people” residing with and navigating through such policies. Social conflicts or tensions resulting from development and relocation policies in China are by no means uncommon (Yu 2007), and can further explain territorial dynamics at Chinese borders. Following the theoretical deconstruction of the territory-state-borders triangle (Agnew 1994; Brenner and Elden 2009; Amilhat-Szary and Giraut 2015), and increasing academic interest in dynamic analysis of state control and regulation expansion through territory building at the border (Rippa 2020; Lu 2021; Plümmer 2022), this research seeks to further clarify the role and extent of residents’ participation in renegotiating and adapting government territorial projects for Chinese borderland margins. Specifically, it uses a geopolitical methodology centred on the analysis of power relations over territories, and empirical fieldwork data collected in Nujiang to study such territorial processes “from below.”

This article is organised as follows. It first defines borders as tools used by the state for the purpose of increasing territorial control and regulation. The conceptual framework then presents the hypothesis that China’s southwestern borderland margins are characterised by distinct local features that shape the power relations resulting from the implementation of top-down borderland development policies. Following the presentation of this research’s methodology and case study, the article is structured into two sections. The first details the main territorial restructuring projects initiated by government actors in Nujiang over the past twenty years. The second examines the possibility and extent of resident agency in negotiating territorial restructuring through protests.

Literature review and conceptual framework

Beyond boundary lines: Borders as state territorial tools

As considered in contemporary border literature (Moraczewska 2010; Amilhat-Szary and Giraut 2015; Laine 2016; Konrad and Brunet-Jailly 2019), restricting the definition of borders to boundary lines risks overlooking other important border functions, as well as the dynamic territorial building processes that occur on one or both sides of a boundary line (You 2024). Looking beyond the line, borders should be considered more than national tools aimed towards international flows. For national governments, they also serve similar goals of controlling and regulating people who live at or behind the line. While China’s state-led population control and regulation practices have been studied in the literature through the lens of hotly debated topics such as birth control and hukou policies (Greenhalgh and Winckler 2005; Wang and Liu 2018), borders have also been increasingly identified as governing tools that function in regulating population or state territory (Amilhat-Szary and Giraut 2015; Plümmer 2022; Zhao 2024). They fulfil territorial functions such as the anchoring of transnational ethnic groups, or the regulation and reorientation of flows of goods and people between national borderlands and national centres and nodes. They jointly target population and land, as the influence over land also allows for terrain control (Elden 2010), which is of state interest in porous border areas where informal practices persist (Lim and Su 2021).

However, in the Chinese case, recent literature has demonstrated that the space surrounding boundary lines is not entirely controlled or produced by the central government that presides over national territory issues. Provincial and local authorities, such as those of Yunnan Province, also contribute to the definition of border functions and dynamics (Ptak and Konrad 2021), as China’s border opening or closing has been found to result from relational dynamics produced at multiple scales, rather than only at the national level (Ptak et al. 2020). Indeed, studies on the evolution of authoritarianism in China’s political system and governance practices show a similar pattern, where the apparent unity of state decisions can in fact be fragmented (Lieberthal and Oksenberg 1988; Mertha 2008; Tsai 2021). Southwest China border politics follows the same fragmentation, decentralisation, and possibility for local adaptation (Plümmer 2022). Thus, as local governments find leeway to modify central government decisions, this research seeks further evidence of bottom-up, local reactions meeting top-down territorial policies, which would further reveal the relational quality of Chinese borderland construction (Rippa 2020).

Borderland margins: Regulation and integration to state territory through territorial restructuring

This article specifically examines a type of borderland that is not yet fully integrated into a modern nation-state such as China, and where central government attempts at borderland regulation and control confront issues of social stability and national cohesion. For instance, before the Second World War, Nujiang was still unmapped by European explorers, and remained under the conflicting influences of Tibetan chieftains, Christian missionaries, and Republican China (Guibaut and Liotard 1941; Gros 2011; McConell 2019). The literature generally refers to such borderlands as “remote border regions” (Hu and Konrad 2017), as “frontiers” during China’s imperial era and chieftain governing system (tusi 土司), or even as “refuges” from the grip of states, and still in the process of being “enclosed” (Scott 2009). They share certain characteristics, which also define them as margins. Being significantly inhabited by ethnic groups who were not previously organised along nation-state border logics, these frontiers are inhabited by “cultural hybrids” (Park 1928, quoted in Ho and Padovani 2020) who dwell in “overlapping political, economic, and cultural boundaries” (Parker 2006). Partially defined by life at and across the border, borderland margins present the governing challenge of their alterity to national norms, as well as the capacity of their residents to appropriate and navigate state policies (Chan and Womack 2016; Bird 2018).

Spatial planning and development are governing tools used by the Chinese state to address the alterity of borderland margins in a holistic way by restructuring their territory to further integrate them into national territory, as in the case of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Rippa 2020). As such, this research argues that continuous development of state territory over such borderland margins can take the shape of territorial restructuring policies that “pulverises space into manageable (…) grids” (Brenner and Elden 2009). In this case, marginality also refers to borderlands’ remote position vis-à-vis the capitalist and modern economic systems, a concern during China’s national development era. Remoteness thus determines the degree of their integration into national and global economies, their relative lack of trade and communication infrastructures, their territorial organisation, and their residents’ possession of professional skills and daily habits that can connect borderlands to regions and networks beyond the border. In this sense, these areas partially overlap with the broader definition of under-developed areas of western China, which have been the focus of development policies related to infrastructure, poverty, and rurality. Further integration and regulation of these borderlands is thus tied to their spatial and territorial organisation (Dean, Sarma, and Rippa 2024).

However, if development governance choices do not sufficiently connect both national and local territorial logics, addressing marginality through territorial restructuring can run counter to existing spatial structures, including those organised and appropriated on an everyday basis by local communities (Brent 2015). In fact, the failure to include resident stakeholders and the multifaceted aspects of their ways of life in decision-making processes has long been identified as a key issue inside and outside of China, especially in national projects such as large dams (Cernea 2000; Habich 2016). Outside of China, some academics argue that state-led development and modernisation ought to be connected with the distinct territorial models of other stakeholders (Vaccaro, Dawson, and Zanotti 2014). Others argue that development projects inevitably involve differing power relations over territory, which should not be seen as abnormal (Olivier de Sardan 2001; Subra 2016).

In China itself, restructuring policies that aim to optimise production, living, and ecological rural spaces are challenging for local social structures, and some rural scholars recognise the importance of bottom-up initiatives to sustainably accomplish rural revitalisation goals (Long 2020). The literature on China’s rural tourism development also highlights how gaps between the interests of different stakeholders (companies, government actors, tourists, residents) can lead to conflicts (Wang and Yotsumoto 2019). In particular, literature related to western Yunnan development shows that the question is not whether resident agency exists, but rather which policy context allows it to emerge, and how it engages with government actors, who have to find diverse and targeted strategies to negotiate their own position between the higher authorities and residents (Habich 2016; Habich-Sobiegalla and Plümmer 2021). Here, agency is defined as the capacity to react to policies within the limits of imposed conditions (Noseda and Racine 2001; Kuus 2019), which points to residents’ limited range of action. While reflecting on border tourism development in Yunnan, Gao et al. (2019) propose avoiding analysis based on strict opposition between hegemony and resistance/agency. Instead, they find that border-making processes result from a complex mix of everyday and spatial practices and representations from all stakeholders, thus further building on the idea of borders as relationally constructed spaces (Paasi and Zimmerbauer 2016).

Methodologically, this article aims to further pursue this relationally constructed idea of borders by choosing a geopolitical approach, as geopolitics specifically studies power relations over territories (Subra 2016), with particular attention paid to distinct subjectivities and the relations between a territory and its actors and agents. The definition of territory as a space actively appropriated by various actors and agents through their interconnected spatial practices, experiences, beliefs, and emotions (Giraut 2008) opens the study of power relations over space beyond the state. On this basis, this study proposes to further explore the role of residents in defining Chinese borderland margins on the basis of both spatial and territorial practices, and under the fairly centralised and pressuring context of the 2010s poverty alleviation campaign.

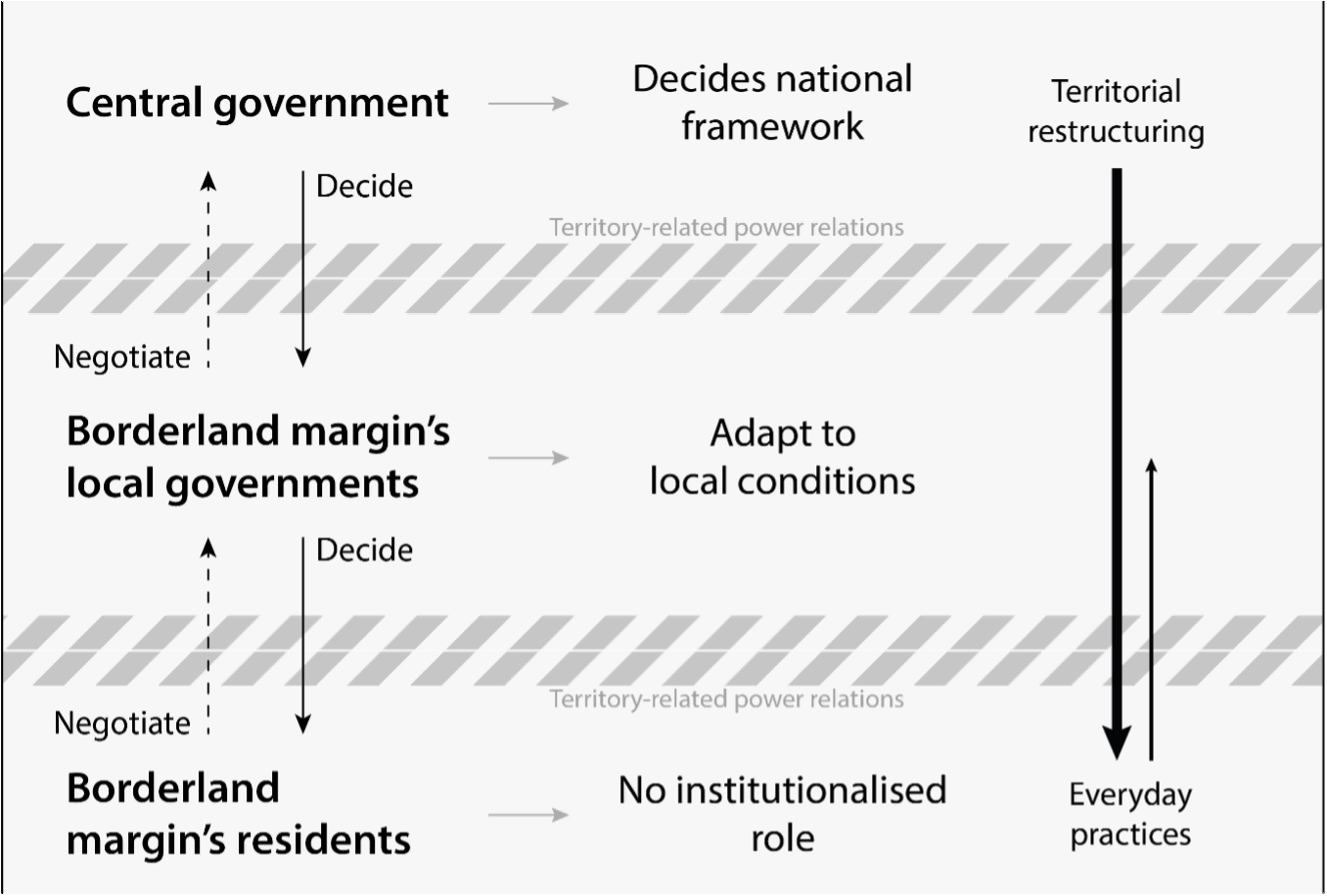

Figure 1. Negotiating territory in China’s borderland margins

Credit: the author.

Research methodology and data collection challenges

Data used in this article were collected for the author’s PhD dissertation, which builds on a geopolitical approach to explain conflicts related to spatial planning in China. Two field trips were conducted in Nujiang during the summer of 2018 (three weeks) and around Christmas 2019 (one week). During both periods, interviews were conducted in rural residential areas. The 2019 fieldwork was largely aimed at consolidating the qualitative data collected in 2018.

The 2018 fieldwork forms the main basis for this article. Its objective was to study government development policies according to the perceptions and opinions of residents, to highlight local issues that do not readily appear in accessible official media but are expressed as important by residents. This fieldwork employed a door-to-door approach designed to facilitate exchanges with people using open-ended questions. No recordings were made, and notes were documented afterwards. Additionally, due to language barriers (in Mandarin, Lisu, and Nu), interviews were facilitated by a Chinese research assistant, which limited the possibility of discourse analysis. Most of the 33 interviews conducted in 2018 were situated around one of Nujiang’s counties, with one specific township and two of its villages receiving more attention. For anonymisation purposes, we have named these localities Wild Forest County, Horse Stream Township, Old Mountain Village, and Cotton Valley Village. The interviewed population was composed primarily of Nu and Lisu males, mostly aged between 30 and 55 years old, engaged in full- or part-time subsistence farming activities. Four of these interviewees were members of the Chinese Communist Party (two individuals), former Party cadres (one individual), or closely associated with them (one individual).

Most interviews with residents resulted in discussions lasting about half an hour. Their repetition across different villages confirmed the relevance of certain topics and helped to restructure interview guidelines over time. Consequently, these guidelines allocated less room for questions related to hydropower, and more to state-society relations and agricultural issues. Longer interviews, ranging from one to two hours, increased the amount of qualitative data related to interviewees’ representations and perceptions on the aforementioned topics.

In addition, I compiled government documents at the national, provincial, and prefecture levels, as well as media articles that presented the views and intentions of government officials. Due to the conflictual atmosphere prevailing around Wild Forest County at the time, no local officials were contacted. To further counterbalance the lack of access to officials, three Chinese environmental nongovernmental organisation (ENGO) members involved in Nujiang’s past hydropower project were contacted in 2018 and 2019. Engaging with these actors provided another viewpoint on the intentions of Chinese government actors and the policies at work in the late 2010s.

This article uses a coding system to refer to individual interviewees. The first two letters indicate the counties where interviews occurred; WF thus stands for Wild Forest, and CR for Clear River. The first two numbers represent the year – with 18 indicating 2018 for instance. The last two numbers represent the chronological order of a given interview in a given county, and this sequence resets for different counties and years. Thus, WF1801 refers to the first interview conducted in 2018 in Wild Forest County. The main declared profession or relevant occupation is listed after the code. A similar system is used for ENGOs, with an ENGO tag followed by a number indicating the specific ENGO interviewed (ENGO1, 2, or 3) and a separate code for the year of the interview. ENGO names are here kept anonymous.

Case presentation: Snapshot of a “lagging behind” borderland margin

Nujiang has been the site of previous power relations opposing hydropower development and environmental protection actors. Notably, apart from energy and environmental issues, controversies also revolved around available development paths accessible for western and ethnic borderland regions (Magee and McDonald 2006). Modernisation also targeted ethnic and traditional life practices, customs, and ways of life,[1] although with softer policies and security requirements than in autonomous regions such as Tibet or Xinjiang (Guo and You 2023), and despite Nujiang bordering the relatively unstable Myanmar Kachin state. Since the advent of the national poverty alleviation campaign launched by Xi Jinping in 2014 under the official declaration “No ethnic minority can be left behind” (yige minzu dou buneng shao 一個民族都不能少), Nujiang fully resumed its modernisation path even for minorities as few as the Dulong.[2]

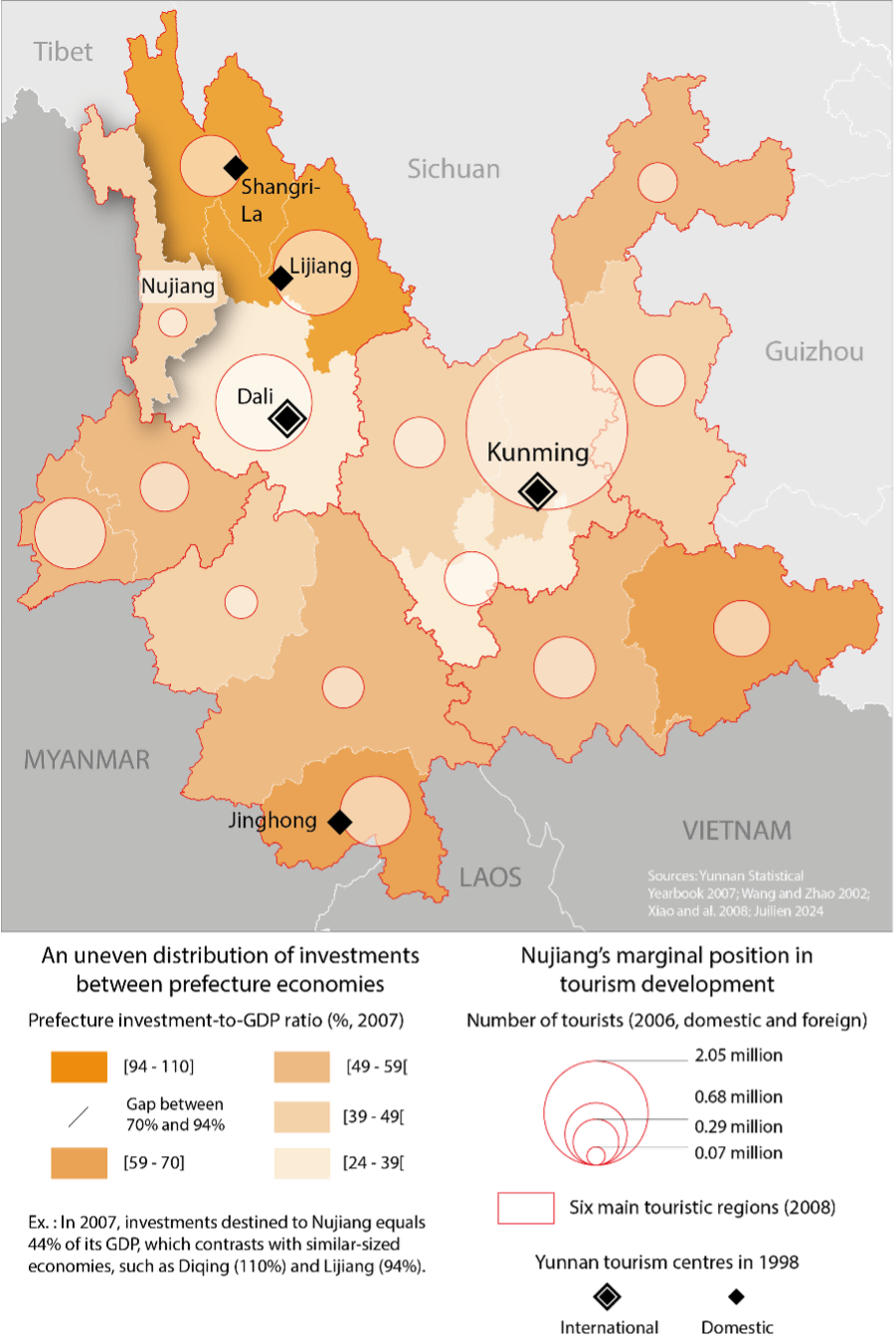

Economically, as a borderland, rural Nujiang enjoys less transborder commercial activity than border ports such as southwest Yunnan’s Ruili. Twenty-first century accounts of the socioeconomic status of Nujiang illustrate separate tracks between the prefecture’s economy and the daily economic activities of its inhabitants. During the 2000s, prefecture revenues were mostly driven by heavy industries (Brown and Xu 2010), while small hydropower plants were built during this period (Ptak 2016). However, as shown in northern Nujiang (ibid.), and as this research’s field observation suggests for Wild Forest County, industry revenues and new electricity generation capacities did not result in comprehensive structural livelihood transformations. According to government actors, the “lagging-behind” quality of ethnic Nujiang is partially rooted in the inhabitants’ “lack of autonomous strength in driving economic growth” (jingji zengzhang nei shengdong li bugou 經濟增長內生動力不夠).[3] While government officials consider relatively lower education and literacy rates to be a challenging factor for Nujiang’s development speed (Harwood 2009), certain government programs aim to open up the valley, such as labour agencies organising the formal export of labour to industrialised eastern provinces. Structurally, this situation also stems from its inhabitants’ reliance on a rural economic system based on mountain subsistence agriculture (including maize, small vegetables, poultry, pork, etc.), instead of “pillar industries” that contribute to Yunnan’s development rate and fiscal revenues (Wang, Xia, and Li 2006; Qin 2007). Figure 2 presents a picture of Nujiang Prefecture’s economic status compared to other Yunnan prefectures during the 2000s, and its overall marginal position in the province at the time.

According to government plans, Nujiang’s marginality and under-development originate from its rural economic structure, its relatively lacking infrastructure,, and the “overall lower quality” (zonghe suzhi bugao 綜合素質不高) of its ethnic minorities.[4] This results in a situation described in government documents as “waiting, relying on, asking” (deng kao yao 等靠要), where the population waits, rely, and ask for regular state subsidies, instead of striving to autonomously develop pillar industries sufficient to employ themselves locally. Overall, these factors are referred to in government planning documents of the late 2010s as elements constitutive of “destitute areas” (te kun diqu 特困地區) presenting “deep poverty” (shendu pinkun 深度貧困) challenges,[5] which are shared by other ethnic borderlands throughout Yunnan (see Figure 2). Finally, the central government and the Yunnan provincial government view poverty not only as an issue in itself, but as intertwined with other national issues: the governance of ethnic minorities, maintaining social stability, border security, and economic growth.[6]

Figure 2. Overview of the marginality of Nujiang Prefecture in Yunnan

Sources: Yunnan Statistical Yearbook 2007, 2020; Zuo 2019.

Credit: the author.

State approach to borderland margin Nujiang: Resolving marginality through development policies

After the presentation of selected elements constitutive of Nujiang’s marginality, this section examines the modernisation of Nujiang from the position of Party-state actors at different administrative levels. It argues that the valley’s consecutive development projects, first hydropower, then tourism, and parallel environmental or anti-poverty policies, share a broader objective of addressing marginality through territorial restructuring. In doing so, this research shows that Nujiang’s development aims to further integrate the valley into the national territory.

Development through hydropower: Building Nujiang’s integration into national territory

Nujiang’s major development pathways were first conceived in the early 2000s and served as a basis for later ones. At the time, the Yunnan government identified three main economic axes to develop Nujiang and consolidate its ties to the province and to China: agriculture, tourism, and resource extraction, such as non-ferrous minerals or hydroelectric resources (Qin 2007). To promote tourism, for instance, the prefecture was integrated into the Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas in 2003 as a UNESCO World Heritage site, based on geological, biodiversity, and landscape assets.[7] The Nujiang government’s discourse followed provincial strategies, and described future development plans as reliant on mining, hydropower, transborder trade, and ethnic tourism.[8]

Hydropower was chosen by central and provincial actors as Nujiang’s main development pillar, despite its potential impacts on UNESCO environmental criteria. The devised Nujiang Hydropower Project (NHP, 2003-2016) was planned to include 13 hydroelectric dams in the prefecture, of which eight were to be located in the Nujiang River Valley, for an electric capacity totalling 21.3 GW. This project was considered a national strategic asset that “optimised” the use of local resources for each government level objective, from the central government to local Nujiang Prefecture.[9] It connected Nujiang to multiple national priorities, such as supplying electricity for eastern provinces, and providing additional renewable sources to reduce coal in China’s energy mix. As hydroelectricity exports were to become an important resource in China’s and Yunnan’s economic development strategies, Nujiang’s water was to play a role in the wider effort of rebalancing national territorial dynamics. It matched the goals of the Great Western Development strategy (xibu da kaifa 西部大開發) launched in 1999 by contributing to a “Send Western Electricity East” (xidian dong song 西電東送) policy to further connect western and eastern provinces, while strengthening Yunnan’ strategy of becoming a “bridgehead” between China’s inland and South and Southeast Asia (Maggee 2006; Summers 2013).

Margin integration through territorial restructuring was also an important objective to both the provincial and prefectural governments. It would have provided a steady stream of revenue to Nujiang Prefecture, estimated at an additional RMB one billion, which would have helped diminish reliance on provincial and national financial subsidies to Nujiang (ENGO2-18). As presented by Qin Guangrong 秦光榮, then Yunnan’s governor (2007-2011), the NHP’s local goal was to lift the valley out of poverty, and tackle its rural issues (social and spatial structure, farming economy).[10] Among other spatial effects of development through dams, dam-induced migration all along the river was part of the effort to gradually transform the valley’s rural and agriculture-based structure towards an urban one, based on other industries.

Because the project has been abandoned, at least for now,[11] the NHP caused few dam-related resettlements or other territorial transformations, apart from allowing small hydropower stations to flourish on Nujiang River tributaries (Ptak 2016). However, the villages that were relocated did prefigure larger-scale urbanisation and territorial restructuring throughout the valley. The case of White Sandbank Village fleshes out this idea. In 2007, preliminary work began to displace the village in preparation for one of the NHP dams. The hydropower company responsible for the NHP, China Huadian, continued to maintain a local office in the new village location in 2018. Apart from controversies surrounding resettlement governance issues, the important point here is that the village inhabitants, small-scale farmers for the most part, were relocated to a new village designed to transition the village’s livelihood towards service economy activities through the restructuring of life space (Brown and Xu 2010). In this case, villagers were financially compensated for land expected to be lost to rising waters, but were not allocated new plots of land. Even if the dam was not built in the end, most inhabitants still turned away from agricultural activities (CL1801, interview with a manual worker). New houses were designed in a standardised fashion for each resettled family, with second floors destined for family life activities and ground floors planned as commercial spaces to support the goal of service-economy transition. This transition was then supported by the 2006 “New Socialist Countryside” (shehui zhuyi xin nongcun jianshe 社會主義新農村建設) national policy, which encouraged the urbanising of villages as well as their development towards industrial or service economies (Ahlers and Schubert 2009).

Using tourism to lift Nujiang out of poverty: A territorial restructuring policy

The NHP was dropped from five-year plans in 2016 after a new Yunnan government turned its attention towards tourism development. Around the same period, in 2015, poverty was targeted under the Five Batches (wuge yipi 五個一批) national policy (comprising measures favouring development, population displacement, ecology, education, and social cohesion), while the Rural Revitalisation Strategy (xiangcun zhenxing zhanlüe guihua 鄉村振興戰略規劃) targeting rural issues was promulgated in 2018. These policies complement one another (Liu and Cao 2017) and increased pressure on local officials to urbanise rural and marginal regions such as Nujiang (ENGO2-18). Following initial plans for tourism development, supported by its 2003 UNESCO listing, tourism was to be the valley’s main development path from 2016 onward. While aiming to increase Nujiang’s position in local and Yunnan tourism circuits, these policies greatly expanded previously initiated territorial restructuring processes.

The following map (Figure 3) illustrates how the valley was initially lagging behind compared to adjacent and comparable prefectures, although foreign companies such as the website Go Kunming and the tour company Last Descents River Expeditions claim that foreign tourism in the form of biking or kayaking trips were emerging during the 2000s. The figure shows how Nujiang was marginalised from the tourist and investment flows of its corresponding northwestern touristic region. The neighbouring Dali–Lijiang–Shangri-La circuit benefitted from more investment and enjoyed better accessibility through highways, rail networks, and airport infrastructure construction. Other Geographic Information System (GIS) maps further detail Nujiang’s relative marginality in comparison with these cities and their surrounding areas (Jian et al. 2017). Integrating Nujiang into Yunnan’s tourism economy while completing anti-poverty goals thus required major investment and spatial transformation to further realise its 2016 “Grand Canyon” (Nujiang da xiagu 怒江大峽谷) economic strategy. This strategy stemmed from Yunnan’s redirection towards mass tourism economy, and is based on Nujiang’s listing as a UNESCO natural heritage.

Figure 3. Yunnan centres and peripheries: A regional snapshot of the tourism industry in the 2000s

Sources: Wang and Zhao 2002; Yunnan Statistical Yearbook 2007; Xiao et al. 2008; Juilien 2024.

Credit: the author.

For the purpose of combined poverty alleviation and tourism development, between 100,000 and 300,000 persons were to be resettled and directed towards new life habits and practices in the span of one five-year plan (2016-2020).[12] Local governments were responsible for relocating up to half of the Nujiang population, which amounted to 249 villages, into 67 new villages located down the mountain and along the Nujiang River during this limited timespan. Besides habitat, restructuring the agricultural system also resulted in a diminution of cultivated land surface, including decreased sugar cane and maize production and implementation of the steep slopes reforesting policy (tuigeng huanlin 退耕還林).

Before discussing agriculture in more detail in the following section, it is useful to first highlight the differences between these new villages, based on their available tourism resources. The design and quality of each “beautiful new village” built during this period has differed significantly, although the rural revitalisation policy in Nujiang supports resettlement planning that fosters a sense of place and belonging in a similar way to hydropower-related resettlement (Habich-Sobiegalla and Plümmer 2022). Old Mountain Village and its surrounding area is a well-off example of this policy orientation which attempts to cater to local situations. Situated higher up in the mountains, at 1,850 metres above sea level on the eastern side of the valley, it offers a good vantage point for contemplating the Gaoligong Mountain Range. The nearby former prefectural seat, nowadays more like a ghost town, has become a tourist attraction due to the preservation of its Maoist-era architecture. Consequently, this village was not entirely relocated down the mountain and near the river, and was recognised as one of Nujiang’s main tourism spots, around which other new villages could be resettled. Hostels provide for tourist accommodation, while new concrete houses are visually enriched with woven bamboo panels reminiscent of local traditional houses. In the nearby mountain, hiking trails paved with volcanic stone panels from the Tengchong area lead to a recently built tea factory indicated on tourist road signs. Spurred by a local entrepreneur and benefitting from fast-growing revenues, nearby mountain farmland has been converted to this expanding local tea industry to serve tourism demand (WF1903, Old Mountain Village tea factory founder).

In Old Mountain Village’s immediate vicinity, a new village has been built for resettled families coming from other nearby mountain villages. Its main public space, built as a sightseeing vantage point, draws special attention to its architectural design, while brand-new three-storey residential buildings display political slogans in bold red characters such as “Feeling grateful to the Chinese Communist Party” (gan’en gongchandang 感恩共產黨), or “The Party’s brilliance illuminates the border” (dang de guanghui zhao bianjiang 党的光輝照邊疆). Its architectural design departs from traditional Nu designs and is more reminiscent of modern styles. Down the mountain, on the other side of the Nu River, the new village of Cotton Valley is more representative of poorer residential areas localised throughout Wild Forest County. Here, house wall paintings signal the village’s location in an ethnic minority area similar to others throughout Yunnan. Facing the river and the Nujiang Highway, these paintings represent scenes of dance or hunting, and are accompanied by black or pink strips dotted with white discs to symbolise ethnicity. While the black strips with white dots mark the existence of a somewhat distinct ethnic territory amid a border province, they tell a story that most interviewed residents could not explain. This field research found that only village elders understood the symbolism, thinking that it represents trade routes that once connected this area to South and Southeast Asian trade networks. This suggests that the symbolism used in the planning of new villages does not smoothly connect with the representations of residents, even if it derives from Nujiang’s transborder history.

Figure 4. A new village built above the ghost town, near Old Mountain Village

Credit: the author.

Figure 5. The resettled Cotton Valley new village, down the mountain

Credit: the author.

Residents upholding their sense of territory amid restructuring: A mark of agency in territory production

While government actors realised territorial restructuring policies in Nujiang with the support of state-owned hydropower companies, residents did not entirely accept all the changes brought to them. This is especially the case where the modernisation of Nujiang and its integration into a market economy involved leapfrogging development stages in a relatively fast-paced fashion. A retired prefectural official held that the central government’s decision to modernise margins such as Nujiang is necessary for the sustainability of its society (WF1816, Old Mountain Village). To him, the debate does not lie in the choice between modernity and tradition, but in balancing them on a case-by-case basis. His view resonates with some approaches in development studies, which reject the binary opposition between modernity and tradition in favour of emphasising the study of their interaction (Olivier de Sardan 2001; Viccaro et al. 2014) – including resulting social tensions. This section will further detail the relative gap between the government modernisation project and residents’ sense of territory. To do so, it reviews protests that attest to the willingness and capacity of residents to renegotiate some of their main concerns with local governments.

The limited scope of resident’s negotiations over resettlement and habitat change

Preferences for certain housing designs are tied to the socio-environmental relations from which Nujiang residents derive their territorial structure. Bamboo and wood, for instance, are accessible in the valley and used as construction materials, but they also constitute the main energy source for heating and cooking. Beyond material considerations, fire pits are also gathering places tied to local social and spiritual organisation (Liu T. 2020). Notably, environmental issues caused by the valley-wide use of local firewood for cooking and heating were among the arguments raised by previous hydropower development proponents to present dam building as an environmental necessity during the 2003-2016 Nujiang large dam controversy (Wang, Xia, and Li 2006).[13] Changing Nujiang residents’ relationship to the valley’s environment was already seen as important.

While discussing ongoing modernisation policies, the previously mentioned retired official explained that, unlike him, most Nujiang prefectural officials viewed the replacement of traditional building materials as necessary, and that multi-storied buildings made of concrete embodied Nujiang’s transition towards modernity (WF1816). Few prefectural officials therefore supported his position, but some residents did express similar preferences for traditional housing: the reasons they mentioned ranged from the higher financial cost associated with modern housing to more qualitative criteria such as traditional housing’s better adaptation to the valley’s subtropical climate. One Lisu couple in their thirties interviewed in Wild Forest County also expressed a preference for wooden houses because of their attachment to ways of life spanning several generations (WF1813). In fact, as the razing and resettlement of villages was still ongoing in 2018, the reliance on traditional dwellings could still be observed in Wild Forest County. They continued to be mentioned when resettlement compensation was deemed insufficient (WF1806, small trader, Black Stone Village), and when concrete houses were deemed impractical (WF1815, hostel owner, Old Mountain Village) or too far from cultivated fields (WF1813, farmer; WF1819, light industry worker, Horse Stream Township).

However, government-led transformation of the relationship between habitat and environment did not lead to large-scale protests or attempts to negotiate fundamental policy objectives. Interviews in Wild Forest and Clear River Counties involved discussions relative to resettlement issues, but they recounted limited scope, village-sized protests aimed at renegotiating specific local details (materials used, house designs, village-level corruption cases…). The case of Black Crow Village (Clear River County), for instance, shows that village-level resident opposition can be successful when the whole village is mobilised, though such mobilisation remains confined to the village scale. In this case, residents were suspicious of an agreement between the local government and a construction materials company. Through protests, they renegotiated house layouts before construction began (CR1802, farmer, Black Crow Village). Compensation amounts were often talked about throughout Wild Forest County, as most families interviewed possessed limited income to navigate important life transformations. However, besides private discussions related to financial compensation or construction defects related to corrupt local officials (WF1818, Party member, Cotton Valley Village), the residents interviewed did not mention significant feelings against their changing ways of inhabiting the valley – except for the banning of maize cultivation. Events such as that in Black Crow Village suggest a capacity to address village-level issues with village mobilisation, which attests to some influence over the organisation of local space.

Maize ban protests: Balancing government imperatives and local stability

Throughout Wild Forest County, larger-scale attempts to negotiate the transformation of the valley did not occur because of population resettlement issues, but because of a government three-year ban (2016-2019) on the cultivation of a single crop, maize. Maize is described by residents as a fundamental local resource that supports the local food system in the absence of regular revenues, as the local economic structure does not provide employment outside of cities (WF1819, farmer). This situation is comparable to many other economically marginalised Chinese rural areas, where the possession of land provides a social security net (Heger 2021). Maize feeds family-raised livestock such as pigs or chickens, and in times of need is also used for human consumption as a substitute for rice, especially now that small hydropower stations limit the use of water for rice paddies throughout the county (WF1818, farmer and Party member; WF1820, farmer). In this situation, the disappearance of maize as a resource for residents forces them to buy their food, makes raising livestock onerous (WF1809, farmer), and creates uncertainty for the near future (WF1813, farmer; WF1815, part-time farmer; WF1820, former farmer). Thus, the cultivation of maize constitutes more than a local practice and is intertwined with the local socioeconomic structure. As a result, the loss of maize caused strong emotional reactions. Interviewed residents expressed their fear that this ban could result in starvation throughout the county’s villages. The obvious impossibility of “eating houses” was simply laid out (WF1819, farmer) or even yelled repeatedly during protests and interviews. Some villagers despaired at the impossibility of finding local employment with decent revenues, while construction companies mobilised for modernisation projects mostly recruited its workforce out of the valley (CR1803).

Despite controversies and worries surrounding the maize ban, its reasoning and origin were difficult to trace during fieldwork. Interviewees were unable to identify with certainty which government level was responsible for it, and received no official explanations besides government calls to trust their decisions and policies (WF1818, farmer). A Party member in Cotton Valley Village claimed to have raised questions to the Horse Stream Township government, but said that he did not receive answers and did not press the issue in order to avoid trouble (WF1818). Others thought that it made sense from an environmental standpoint, as maize roots are shallow and contribute to undermining mountain soil in a region prone to landslides (WF1822, schoolteacher). The retired prefectural official mentioned earlier speculated that maize had low market value; that the economic prospects of animal husbandry were limited because of transportation issues, thus reducing the benefit of growing maize; or that maize plants turned yellow after harvesting and reduced the visual appeal for touristic Nujiang (WF1816). An in early 2018 online government response to citizen questions confirmed these hypotheses, and details that this ban resulted from plans to restructure the prefecture’s agricultural sector towards crops that are more profitable and environmentally-friendly.[14]

Despite the existence of this online response, the perceived opacity of the local government led to further rumours. Interviewees pondered the influence of hydropower company China Huadian over prefecture officials, as it assumed responsibility for anti-poverty work (WF1815, hostel owner; WF1816, ex-official). Leading Party cadres were also described as illegitimate (ibid., WF1806, WF1819, CR1803), leading to plans to petition for the resignation of county and prefecture cadres in one case (WF1820). Eventually, perceptions about local government officials and fears of hunger gave rise to resistance and protests throughout the county, especially as some villagers refused to replace maize with commercial crops. Those who refused to dig up their maize crops faced the withdrawal of government allowances, such as the subsistence allowance (低保 dibao) allocated to families with limited resources, or the intervention of enforcement officers to cut down remaining maize crops.

Direct confrontations between village groups and local officials were not witnessed during fieldwork, but were related by interviewees, some of whom shared videos. Although protest leaders who publicly confronted officials in town meetings were inaccessible to us even one year later, their appearance in shared WeChat videos suggests their capacity to lead residents and to communicate the importance of local demands relative to maize. Some of these videos show accusations against current officials, such as “knowing nothing else than bullying,” or “not understanding that the local population lives a difficult life” while officials “enjoy income ten times higher.” These videos also show that some residents have tried to use their social connections, for instance by reaching out to a former prefectural deputy secretary and seeking confirmation of the source of the maize ban – which led to the conclusion that no official documents confirm this ban. Protests have also been organised in front of the county seat. Physical violence against Party officials was mentioned during interviews (WF1820). As described by one interviewee, such unrest is tied to “strange public policies” carried out in the name of tourism development, anti-poverty measures, and environmental protection, which have not been explained to or understood by residents (WF1815).

This policy was eventually reversed, and the maize ban was lifted in 2019 (WF1901, hostel owner). Residents restored their right to grow maize through collective (and occasionally violent) action. From a territorial point of view, they reappropriated land that government actors had planned for commercial crops. The maize crops that they resumed growing form the basis of the local subsistence agriculture system, and are an essential link in Nujiang residents’ sense of territory. The relevance of this sense of territory in the restructuring of Nujiang, expressed and communicated through county-wide protests, was therefore acknowledged by local governments in order to maintain social stability, even if it went against the original planning to some extent. As long as the protests did not target core objectives such as urbanisation, tourism development, and cash crop cultivation, this limitation supports the idea of margin residents’ agency, which remains not active but re-active, and within the bounds of central policies serving the goals of margin integration through restructuring.

Discussion and concluding perspectives

This case study of the restructuring of Nujiang River Valley offers insights into the territorial dynamics at work in a Chinese borderland characterised by its relative remoteness and marginality to national territory, and where the state is consolidating its political and administrative grip over land and population. Here, under policy discourses of modernisation and poverty alleviation, the development and territorial restructuring of this borderland by government actors aims to reinforce national cohesion and extend state regulatory capacity over borderland margin residents. Nujiang’s case study highlights state population regulation organised through territorial restructuring, where spatial planning designed from the perspective of state objectives selects which livelihood practices are to be kept or rejected. Selected elements of restructuring include resettlement in urbanised and modernised villages, commodification processes of agricultural land from subsistence functions to cash crops, and planning for tourism development. These transformations respond to China’s state objectives of further integration into market economies.

As in the case of Chinese hydropower-related resettlements (Habich-Sobiegalla and Plümmer 2022), such restructuring in rural border areas also builds on fostering a feeling of belonging, which further favours social stability in borderland and ethnic margins. However, in this case, targeted poverty alleviation still produced power relations in the form of conflicts between residents and local authorities responsible for policy adaptation and implementation. This article reviews two territorial restructuring elements that resulted in resident protests to renegotiate policies in one of Nujiang’s counties. It first finds that resettlement and habitat changes spurred village-scaled protests that resulted in renegotiated house layout designs. This first case highlights the potential for ordinary protests, even if local authorities acted under the context of a national priority policy. As suggested in literature studying development in Yunnan, gradual state shifts towards human-oriented policies enable some degree of resident empowerment (Habich 2016; Gao et al. 2019; Habich-Sobiegalla and Plümmer 2021) that allows for renegotiation. A maize cultivation ban was the second source of unrest studied in this research. It shows how resident agency to negotiate through protests can grow in scale when local adaptation of territorial restructuring policies pushes too far against their own sense of territory – which here stems from the daily practices of subsistence agriculture.

Finally, considering that social conflicts are part of development and planning projects, such protests can be interpreted as the meeting of two territorial models: the national territory model produced by state actors under policy frameworks, and the borderland margin resident territory model that was organised to sustain its residents. However, following theories related to the relational construction aspect of borders in general (Paasi and Zimmerbauer 2016) and in Yunnan in particular (Gao and al. 2019), this research explains these power relations not as a strict confrontation between dominant actors and marginalised stakeholders, but rather as constitutive of Nujiang’s territorial construction. From this point of view, protests partially resolve the power balance between local governments and residents (Wang and Yotsumoto 2019). This type of violence, organised by residents as agents pursuing negotiations, is thus constitutive of territory construction dynamics (Sargeson 2013), and follows the boundaries of national policy frameworks. Territorial restructuring projects are not wholly rejected by residents as in the case of large hydropower dams throughout the 2000s (Mertha 2008), but are negotiated and adapted to their interests.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the guest editor, You Tianlong, for his constructive feedback, to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful criticism, to the editors for their support, and to Pierre Miège for his generous help.

Manuscript received on 3 July. Accepted on 9 December 2024.

References

AGNEW, John. 1994. “The Territorial Trap: The Geographical Assumptions of International Relations Theory.” Review of International Political Economy 1(1): 53-80.

AHLERS, Anne, and Gunter SCHUBERT. 2009. “‘Building a New Socialist Countryside’ – Only a Political Slogan?” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 38(4): 35-62.

AMILHAT-SZARY, Anne-Laure, and Frédéric GIRAUT. 2015. “Borderities: The Politics of Contemporary Mobile Borders.” In Anne-Laure AMILHAT-SZARY, and Frédéric GIRAUT (eds.), Borderities: The Politics of Contemporary Mobile Borders. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 1-19.

BIRD, Joshua. 2018. Economic Development in China’s Northwest: Entrepreneurship and Identity along China’s Multi-ethnic Borderlands. London: Routledge.

BRENNER, Neil, and Stuart ELDEN. 2009. “Henri Lefebvre on State, Space, Territory.” International Political Sociology 3(4): 353-77.

BRENT, Zoe W. 2015. “Territorial Restructuring and Resistance in Argentina.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 42(3-4): 671-94.

BROWN, Philip, and Kevin XU. 2010. “Hydropower Development and Resettlement Policy on China’s Nu River.” Journal of Contemporary China 19(66): 777-97.

CERNEA, Michael. 2000. “Risks, Safeguards and Construction: A Model for Population Displacement and Resettlement.” Economic and Political Weekly 35(41): 3659-78.

CHAN, Yuk Wah, and Brantly WOMACK. 2016. “Not Merely a Border: Borderland Governance, Development, and Transborder Relations in Asia.” Asian Anthropology 15(2): 95-103.

DEAN, Karin, Jasnea SARMA, and Alessandro RIPPA. 2024. “Infrastructures and B/ordering: How Chinese Projects are Ordering China-Myanmar Border Spaces.” Territory, Politics, Governance 12(8): 1177-98.

DONALDSON, John. 2007. “Tourism, Development and Poverty Reduction in Guizhou and Yunnan.” The China Quarterly 190: 333-51.

ELDEN, Stuart. 2010. “Land, Terrain, Territoriality.” Progress in Human Geography 34(6): 799-817.

GAO, Jun, Chris RYAN, Jenny CAVE, and Chaozhi ZHANG. 2019. “Tourism Border-making: A Political Economy of China’s Border Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 76: 1-13.

GIRAUT, Frédéric. 2008. “Conceptualiser le territoire” (Conceptualising territory). Historiens et Géographes 403: 57-68.

GREENHALGH, Susan, and Edwin WINCKLER. 2005. Governing China’s Population. From Leninist to Neoliberal Biopolitics. Redwood: Stanford University Press.

GROS, Stéphane. 2011. “Economic Marginalization and Social Identity among the Drung People of Northwest Yunnan.” In Jean MICHAUD, and Tim FORSYTH (eds.), Moving Mountains: Ethnicity and Livelihood in Highland China, Vietnam, and Laos. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. 28-49.

GUIBAUT, André, and Louis LIOTARD. 1941. “Les Gorges de la Salouen Moyenne et les Montagnes entre Salouen et Mékong” (The middle Salween gorges and the mountains between Salween and Mekong). Annales de Géographie 50(83): 180-95.

GUO, Taihui, and Tianlong YOU. 2023. “Creating the Governable Population: Authoritarian Cultural Citizenship and the Ethnic Minorities in a Sino-Tibetan Intercultural Area in Contemporary China.” Citizenship Studies 27(6): 654-72.

HABICH, Sabrina. 2016. Dams, Migration and Authoritarianism in China: The Local State in Yunnan. London: Routledge.

HABICH-SOBIEGALLA, Sabrina, and Franziska PLÜMMER. 2021. “Social Stability, Migrant Subjectivities, and Citizenship in China’s Resettlement Policies.” In Jean-François ROUSSEAU, and Sabrina HABICH-SOBIEGALLA (eds.), The Political Economy of Hydropower in Southwest China and Beyond. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 107-23.

HARWOOD, Russel. 2009. Negotiating Modernity at China’s Periphery: An Investigation of Development and Policy Interventions in Nujiang Prefecture. PhD dissertation. Perth: University of Western Australia.

HEGER, Isabel. 2021. “More than ‘Peasants without Land’: Individualisation and Identity Formation of Landless Peasants in the Process of China’s State-led Rural Urbanisation.” Journal of Chinese Current Affairs 49(3): 332-56.

HO, Wing Chung, and Florence PADOVANI. 2020. “Introduction: Why Use the Concept of Marginality Today?” In Wing Chung HO, and Florence PADOVANI (eds.), Living in the Margins in Mainland China, Hong Kong and India. London: Routledge. 1-35.

HU, Zhiding, and Victor KONRAD. 2018. “In the Space between Exception and Integration: The Kokang Borderlands on the Periphery of China and Myanmar.” Geopolitics 23(1): 147-79.

JIAN, Haiyuan, Haixiao PAN, Guo XIONG, and Xiaorong LIN. 2017. “The Impacts of Civil Airport Layout to Yunnan Local Tourism Industry.” Transportation Research Procedia 25: 77-91.

JUILIEN, David. 2024. La participation de la société à la production des territoires en Chine. Approche géopolitique de la vallée du fleuve Nu (Yunnan), entre 2003 et 2019 (The participation of society in the production of territories in China. Geopolitical approach to the Nu River Valley (Yunnan), between 2003 and 2019). PhD Dissertation. Paris: Université Paris 8.

KONRAD, Viktor. 2021. “New Directions at the Post-globalization Border.” Journal of Border Studies 36(5): 713-26.

KONRAD, Viktor, and Emmanuel BRUNET-JAILLY. 2019. “Approaching Borders, Creating Borderland Spaces, and Exploring the Evolving Borders between Canada and the United States.” The Canadian Geographer 63(1): 4-10.

KUUS, Merje. 2019. “Political Geography I: Agency.” Progress in Human Geography 43(1): 163-71.

LAINE, Jussi. 2016. “The Multiscalar Production of Borders.” Geopolitics 21(3): 465-82.

LIM, Kean Fan, and Xiaobo SU. 2021. “Cross-border Market Building for Narcotics Control: A Polanyian Analysis of the China-Myanmar Border Region.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 46(4): 834-49.

LIU, Shiyao. 2023. “Research on Anti-poverty Efforts in China’s Ethnic Minority Areas since the 1970s.” International Journal of Anthropology and Ethnology 7(17). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41257-023-00096-x

LIU, Ting 劉婷. 2020. “旅遊空間再造與傳統村落的文化適應研究: 雲南省怒江州百花嶺村的研究案例” (Lüyou kongjian zaizao yu chuantong cunluo de wenhua shiying yanjiu: Yunnan sheng Nujiang zhou Baihualing cun de yanjiu anli, Tourism spatial reconstruction and cultural adaptation of traditional villages: A case study of Baihualing Village, Nujiang Prefecture, Yunnan Province). Guizhou minzu yanjiu (貴州民族研究) 41(9): 48-56.

LIU, Yansui 劉彥隨, and CAO Zhi 曹智. 2017. “精准扶貧供給側結構及其改革策略” (Jingzhun fupin gongji ce jiegou jiqi gaige celüe, Supply-side structural reforms and its strategy for targeted poverty alleviation in China). Zhongguo kexueyuan yuankan (中國科學院院刊) 32(10): 1066-73.

LIU, Yansui, Jilai LIU, and Yang ZHOU. 2017. “Spatio-temporal Patterns of Rural Poverty in China and Targeted Poverty Alleviation Strategies.” Journal of Rural Studies 52: 66-75.

LIEBERTHAL, Kenneth, and Michel OKSENBERG. 1988. Policy Making in China: Leaders, Structures, and Processes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

LONG, Hualou. 2020. Land Use Transitions and Rural Restructuring in China. Cham: Springer.

LU, Xiaoxuan. 2021. “Re-territorializing Mengla: From ‘Backwater’ to ‘Bridgehead’ of China’s Socio-economic Development.” Cities 117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103311

MAGEE, Darrin. 2006. “Powershed Politics: Yunnan Hydropower under Great Western Development.” The China Quarterly 185: 23-41.

MAGEE, Darrin, and Kristen McDONALD. 2006. “Beyond Three Gorges: Nu River Hydropower and Energy Decision Politics in China.” Asian Geographer 25(1-2): 39-60.

McCONNELL, Walter. 2019. “God’s Mission to the Lisu.” Mission Round Table 14(1): 24-34.

MERTHA, Andrew. 2008. China’s Water Warriors: Citizen Action and Policy Change. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

MORACZEWSKA, Anna. 2010. “The Changing Interpretation of Border Functions in International Relations.” Revista Romana de Geografie Politica 2: 329-40.

NOSEDA, Veronica, and Jean-Bernard RACINE. 2001. “Acteurs et agents, points de vue géographiques au sein des sciences sociales” (Actors and agents, geographical points of view within social sciences). Revue Européenne des Sciences Sociales 39(121): 65-79.

OLIVIER DE SARDAN, Jean-Pierre. 2001. “Les trois approches en anthropologie du développement” (The three approaches in development anthropology). Tiers-Monde 42(168): 729-54.

PAASI, Anssi, and Kaj ZIMMERBAUER. 2016. “Penumbral Borders and Planning Paradoxes: Relational Thinking and the Question of Borders in Spatial Planning.” Environment and Planning A 48(1): 75-93.

PARK, Robert. 1928. “Human Migration and the Marginal Man.” American Journal of Sociology 33(6): 881-93.

PARKER, Bradley. 2006. “Toward an Understanding of Borderland Processes.” American Antiquity 71(1): 77-100.

PLÜMMER, Franziska. 2022. Rethinking Authority in China’s Border Regime: Regulating the Irregular. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

PTAK, Thomas. 2016. Understanding Hydropower in China: Balancing Energy, Security, Development and Environmental Sustainability in the Nu River Valley of Yunnan Province. PhD dissertation. Eugene: University of Oregon.

PTAK, Thomas, and Viktor KONRAD. 2021. “‘Crossing the River by Feeling the Stones’: How Borders, Energy Development and Ongoing Experimentation Shape the Dynamic Transformations of Yunnan Province.” Journal of Borderland Studies 36(5): 765-89.

PTAK, Thomas, Jussi LAINE, Zhiding HU, Yuli LIU, Viktor KONRAD, and Martin van der VELDE. 2020. “Understanding Borders through Dynamic Processes: Capturing Relational Motion from South-West China’s Radiation Centre.” Territory, Politics, Governance 10(2): 200-18.

QIN, Chengxun 秦成遜. 2007. “雲南省支柱產業發展的現狀, 問題和對策研究” (Yunnan sheng zhizhu chanye fazhan de xianzhuang, wenti he duice yanjiu, Study on the present conditions, existing problems and related countermeasures of the pillar industries in Yunnan). Kunming ligong daxue xuebao (昆明理工大學學報) 32(4): 85-9.

RIPPA, Alessandro. 2020. Borderland Infrastructures. Trade, Development, and Control in Western China. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

SARGESON, Sally. 2013. “Violence as Development: Land Expropriation and China’s Urbanization.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 40(6): 1063-85.

SCOTT, James. 2009. The Art of not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Press.

SUBRA, Philippe. 2016. Géopolitique locale. Territoire, acteurs, conflits (Local geopolitics: Territory, actors, conflicts). Paris: Armand Colin.

SUMMERS, Tim. 2013. Yunnan – A Chinese Bridgehead to Asia. A Case Study of China’s Political and Economic Relations with its Neighbours. Sebastopol: Chandos Publishing.

TSAI, Kellee. 2021. “Evolutionary Governance in China: State-society Interactions under Authoritarianism.” In Szu-Chien HSU, Kellee TSAI, and Chun-Chih CHANG (eds.), Evolutionary Governance in China: State-society Relations under Authoritarianism. Harvard University Asia Centre. 3-37.

VACCARO, Ismael, Allan DAWSON, and Laura ZANOTTI. 2014. “Negotiating Territoriality: Spatial Dialogues between State and Tradition.” In Allan DAWSON, Laura ZANOTTI, and Ismael VACCARO (eds.), Negotiating Territoriality: Spatial Dialogues between State and Tradition. London: Routledge. 1-17.

WANG, Fenglong, and Yungang LIU. 2018. “Interpreting Chinese Hukou System from a Foucauldian Perspective.” Urban Policy and Research 36(2): 153-67.

WANG, Jiaxue 王嘉學, XIA Shulian 夏淑蓮, and LI Peiying 李培英. 2006. “三江並流世界自然遺產保護中的怒江峽谷脫貧問題探討” (Sanjiang bingliu shijie ziran yichan baohu zhong de Nujiang xiagu tuopin wenti tantao, Discussion on poverty alleviation in Nujiang gorge in the protection of Three Parallel Rivers World Natural Heritage). Shengtai jingji (生態經濟) 1: 31-4.

WANG, Liguo, and Yukio YOTSUMOTO. 2019. “Conflict in Tourism Development in Rural China.” Tourism Management 70: 188-200.

WANG, Xiaochun 王筱春, and ZHAO Shilin 趙世林. 2002. “雲南旅遊目地的空間結構研究” (Yunnan lüyou mudi de kongjian jiegou yanjiu, On the layout structure of the tourist destinations in Yunnan). Dilixue yu guotu yanjiu (地理學與國土研究) 18(1): 99-102.

XIAO, Bo 肖波, WANG Jiaxue 王嘉學, LÜ Lijun 呂利軍, and BAI Haixia 白海霞. 2008. “雲南旅遊非均衡態勢與演替分析” (Yunnan lüyou fei junheng taishi yu yanti fenxi, Study of unbalanced development and cause of tourism economy in Yunnan). Yunnan dili huanjing yanjiu (雲南地理環境研究) 6: 99-104.

YOU, Tianlong. 2024. “Global China’s Borderlands: Contemporary Characteristics in a Historical Trajectory.” China Perspectives 138: 3-8.

YU, Jianrong. 2007. “Social Conflict in Rural China.” China Security 3(2): 2-17.

YU, Xiaogang, Xiangxue CHEN, Carl MIDDLETON, and Nicholas LO. 2018. “Charting New Pathways towards Inclusive and Sustainable Development of the Nu River Valley.” Green Watershed and Center for Social Development Studies. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University.

ZENG, Qingjie. 2019. “Managed Campaign and Bureaucratic Institutions in China: Evidence from the Targeted Poverty Alleviation Program.” Journal of Contemporary China 29(123): 400-15.

ZHAO, Xuan. 2024. “Borders as Dispositif: Sovereignty, Discipline, and Governmentality at the China-Kazakhstan Border.” China Perspectives 138: 33-44.

ZUO, Changsheng. 2019. “Regional Development and Poverty Reduction in Contiguous Destitute Areas (2011-2020).” In Changsheng ZUO (ed.), The Evolution of China’s Poverty Alleviation and Development Policy (2011-2020). Cham: Springer. 71-105.

[1] State Council of the People’s Republic of China 中華人民共和國國務, “關於印發中國農村扶貧開發綱要(2001-2010年)的通知” (Guanyu yinfa Zhongguo nongcun fupin kaifa wangyao (2001-2010 nian) de tongzhi, Notice on Issuing China’s Rural Poverty Alleviation and Development Outline (2001-2010)), 13 June 2001, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-09/23/content_5111138.htm (accessed on 7 December 2024).

[2] “整族脫貧的獨龍族經驗” (Zheng zu tuopin de dulongzu jingyan, Dulong ethnic group’s experience in alleviating poverty), Zhongguo shehui kexueyuan (中國社會科學院), 22 December 2020, https://www.cssn.cn/mzx/xksy_rmt/202208/t20220803_5447451.shtml (accessed on 7 December 2024).

[3] Nujiang Prefecture People’s Government 怒江州人民政府, “關於印發怒江傈僳族自治州國民經濟和社會發展第十四個五年規劃和二〇三五年遠景目標綱要的通知” (Guanyu yinfa Nujiang lisuzu zizhizhou guomin jingji he shehui fazhan di shisi ge wunian guihua he er ling san wu nian yuanjing mubiao gangyao de tongzhi, Notice on Issuing the 14th Five-year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture and the Outline of Long-term Goals for 2035), 10 March 2021, https://www.nujiang.gov.cn/xxgk/015279139/info/2021-159798.html (accessed on 7 December 2024).

[4] “雲南省脫貧攻堅規劃(2016-2020年)” (Yunnan sheng tuopin gongjian guihua (2016-2020 nian), Yunnan provincial poverty alleviation plan (2016-2020)), 16 November 2018, https://www.jianpincn.com/zgjpsjk/zcwj/dfzc/yn/614259.html (accessed on 7 December 2024).

[5] “雲南省脫貧(…)” (Yunnan sheng tuopin (…), Yunnan provincial poverty (…)), op. cit.

[6] “雲南省脫貧(…)” (Yunnan sheng tuopin (…), Yunnan provincial poverty (…)), op. cit.

[7] Ministry of Construction of the People’s Republic of China, 2003, “Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas,” World Heritage Scanned Nomination No. 1083, https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/1083.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024)

[8] Le Zhiwei 樂志偉 and Wang Yaping 王婭萍, “怒江中下游水電開發. 大峽谷兒女呼喚同步小康” (Nujiang zhongxia you shuidian kaifa. Da xiagu ernü huhuan tongbu xiaokang, Hydropower development in the middle and lower reaches of Nujiang. Sons and daughters of the grand canyon call for parallel prosperity), Yunnan ribao (雲南日報), 19 October 2003.

[9] Le Zhiwei 樂志偉 and Wang Yaping 王婭萍, “怒江中下(…)” (Nujiang zhongxia (…), Hydropower development (…)), op. cit.

[10] Wang Yonggang 王永剛, “秦光榮: 建設以水電為主的電力支柱產業” (Qin Guangrong: Jianshe yi shuidian weizhu de dianli zhizhu chanye, Qin Guangrong: Building a hydropower-based electric power pillar industry), Yunnan ribao (雲南日報), 27 April 2007.

[11] There have been no official documents signalling an official drop of this project (see Yu et al. 2018)..

[12] Nujiang Prefecture People’s Government 怒江州人民政府, “關於印發怒江傈僳 (…),” (Guanyu yinfa Nujiang lisu (…), Notice on Issuing (…)), op. cit.

[13] The Nujiang large dam controversy was a power struggle first opposing the national environmental administration and actors supporting hydropower-based development solutions. It was first based around the use of the Environmental Impact Assessment Law (2003), but rapidly involved ENGOs, which more broadly opposed the development of dams as conceived by the Chinese hydropower industry (Mertha 2008).

[14] “關於怒江州政府要求老百姓不要種農作物的要求” (Guanyu Nujiangzhou zhengfu yaoqiu laobaixing bu yao zhong nongzuowu de yaoqiu, About the Nujiang government demand to not let ordinary people grow crops), 地方領導留言板 (Difang lingdao liuxinban, Message board to local leaders), 5 February 2018 (not online anymore).