BOOK REVIEWS

Reconnecting Spatialities in Uninhabited Industrial Spaces: Ruination and Sense of Place in a Coal Town (Datong, Shanxi)

Introduction

An abandoned coal town: Kouquan

Located on Datong’s outskirts, Kouquan Town used to be an important coal centre, surrounded by mines and miners’ settlements. Today, the coal town looks deserted, with more abandoned buildings and houses than occupied ones. In a cinematic narrative, Kouquan Old Town is one of the locations of the film Ash is Purest White (Jianghu ernü 江湖兒女), directed by Shanxi-based Jia Zhangke 賈樟柯 and released in 2018. The film, set in 2001, tells the story of a woman’s love for an outlaw. The coal transition is an important background: the heroine is the daughter of a coal miner. She is seen visiting her father at a moment when the mine, targeted for closure, is the site of miners’ protests. The heroine is then filmed walking with her lover in an abandoned street of Kouquan Town.

There she smells the hollyhocks that grow along the sidewalk. The abandoned buildings constitute a romantic setting. During their conversation, the man says, “Datong will develop and demolish very quickly,” a hidden reference to Geng Yanbo’s 耿彥波 plan for the city centre’s redevelopment. In 2008, the Geng Yanbo administration initiated a strategy to redefine the city, from “coal capital” (meidu 煤都) to “historical and cultural ancient city” (lishi wenhua gucheng 歷史文化古城). In contrast to the intensity of urban demolition in the city centre, the filmed footage in Kouquan Town immortalises another process of ruination in a narrative of slow rhythms, silence, and intimacy. The film was praised by the local press[1] and recent press reports mentioned another film being shot there.[2] Jia Zhangke’s film inspired fans to visit the place and publish their short films and photos online.[3] However, when I mentioned Jia Zhangke’s film to a group of local residents chatting in Kouquan’s main street, they had never heard of it. This discrepancy between Chinese cinema’s cultural scene and local residents’ experiences suggests that the narratives of the abandoned town are not unified and deserve closer study.

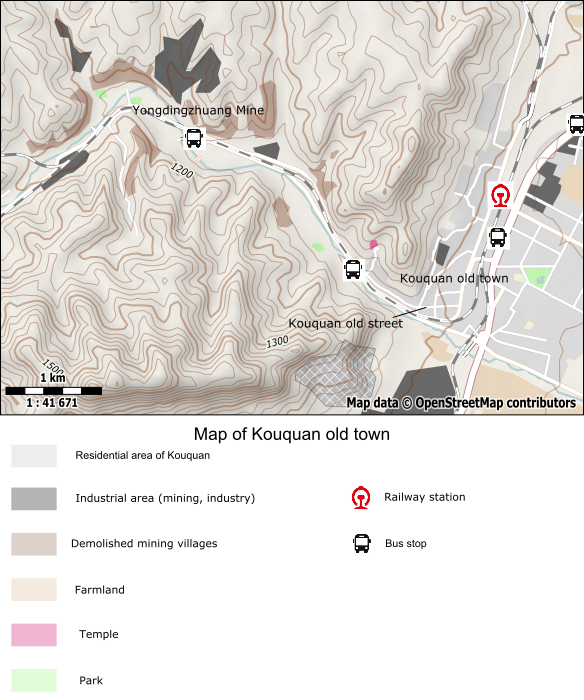

The development of Datong, a medium-sized city in Northern Shanxi, has been based around the coal mining industry since the early twentieth century. Kouquan Town (Kouquan zhen 口泉鎮) is located 20 kilometres from the city centre in the southwestern outskirts, where coal mining settlements formed a dense network of villages near the mines. Kouquan grew in size and in population as the centre of the coal mining industry. In the 1990s, new urban infrastructure emerged around the coal economy, and Kouquan Town became less relevant for consumption and services. In recent years, anti-pollution and de-capacity measures contributed to profound change both in the landscape and in the structure of the coal industry (Audin 2020). Issues of pollution, poor living standards, and land-subsidence impacted the local villages for decades. In 2007, a large-scale urban renewal operation was implemented by the public authorities and by Datong Coal Mine Group (hereafter Tongmei), the state-owned enterprise in charge of most mines, displacing most families of coal miners from shanty towns (penghuqu棚戶區) to new relocation buildings. The coal mine area is now much less densely populated, and old Kouquan has lost most of its functions as a town centre. The ruination process in Kouquan is due to the population moving out, the lack of maintenance of old buildings, and mining-induced land-subsidence issues. Yet, while most residents have moved away, about 200 people still live in Kouquan Old Town. How do they relate to the deserted space? Is ruination only a process of unmaking? Can decay stimulate specific forms of dwelling and recreate a sense of place? Ruination in Kouquan is conceived as a social process that does not follow the temporality of fast urban redevelopment and heritage-oriented planning; nor does it correspond with full decline and abandonment. I consider ruination as a socio-spatial process producing various spatial experiences and articulating unrelated discourses, and allowing both local residents and other actors to remain connected to Kouquan.

Ruination in Kouquan: An entry into uninhabited industrial spaces

Apart from an important range of research on ruination in the field of cultural studies (Wu 2012; Ortells-Nicollau 2015), visual studies,[4] and history with Li Jie’s investigation of the “utopian” ruins of Maoist memory (2020), qualitative research and fieldwork on ruination in China mainly revolve around the violent experience of “demolition-relocation” (chaiqian 拆遷) (Ren 2014) and the resistance of residents in large cities (Ho 2013; Shao 2013). Uninhabited Kouquan Town shows another reality of contemporary ruins: the reality of slow ruination in industrial spaces located far from the main axes of circulation and urban density.

Existing research on industrial spaces mainly focuses on the work unit (danwei 單位), urban poverty in Northeast China (Cho 2013), and shrinkage (Long and Gao 2019), but less on ruination in context.[5] Kouquan is an industrial space, but the work unit is no longer visible. Among existing studies on the varied forms of industrialism (Lean 2020), on industrial spaces (Gillette 2016; Lam 2020), and on coal mining (Yu, Zhang, and Zhou 2008; Zhang 2013; Yang, Zhao, and Ho 2017), there are few social studies on ruination, dwelling, and memory in mining villages and towns. This article details the spatial features of ruination in Kouquan, where the former spaces of miners’ everyday lives are rooted in the local landscape.

Moreover, most of the research on industrial spaces focuses either on shrinkage and decline, or on the strategies of revitalisation through cultural heritage: from the “creative city” to “urban branding,” industrial spaces in Chinese cities have transformed under “artistic urbanization” (Ren and Sun 2012) and “creative industry” (Yung, Chan, and Xu 2014). However, Alice Mah explains that “not all cities can succeed in a competitive model. (…) These stories tend to be overlooked in the interest of a progress-oriented view” (2012: 7). Marie Boyd Gillette states that China’s governments “have not seen industrial heritage as a marketable resource for redevelopment and have instead removed remnants of China’s socialist past” (2017). In Datong, the city administration promoted an ambitious urban planning project in order to change the coal stigma.[6] Datong became the object of an ancient city theming operation through architecture. Datong was the capital of the Northern Wei Dynasty from 398 to 493 C.E.[7] The city administration branded the ancient past as a means to develop a new, marketable image. Datong’s post-coal identity appears in its administrative restructuring. On the eastern city outskirts, far from the mines, a new district was created, attracting the local population and investors around new poles of development. A university, a high-tech zone, and the new high-speed train station have spurred the creation of new residential compounds, amenities, and services. In 2018, the Mining District (Kuangqu 礦區) was cancelled. It is now part of Yungang District (Yungangqu 雲崗區), putting the Yungang Grottoes – a cultural heritage site listed by UNESCO – at the centre.[8]

While Geng Yanbo’s project to redefine Datong has been studied (Cui 2018; Fu and Hillier 2018), moving away from Datong’s city centre, I decided to study the social and spatial structure of the city’s southwestern outskirts, more precisely workers’ neighbourhoods and villages near the coal mines. There, the imprint of the work unit is strong, with the company logo and banners in both the workplace and the residence place. Because they are “marked” by the work unit, these industrial spaces constitute corporate industrial spaces. Kouquan used to be a key location for the coal industry. The local mining government was located there: in the 1950s, the mining district was officially named “Kouquan Mining District People’s Government” (Kouquan Kuangqu renmin zhengfu 口泉礦區人民政府) and then “Kouquan District” (Kouquanqu 口泉區) before it took the name “Mining District” (Kuangqu 礦區) in 1970, which discloses that Kouquan was originally at the centre of the coal production. Official reports presented Kouquan in the 1980s as “a historical (gulao 古老) yet newly emerging (xinxing 新興) industrial site (gongye diqu 工業地區).”[9] The circulation of coal passed through the coal hub of Kouquan via roads and railways, but today, the town no longer appears as a space of production. State-owned enterprises such as Tongmei are not directly involved in local governance. The city administration governs the town from afar. Few residents remain, waiting for their relocation, and most of the built environment is in disrepair. These circumstances lead to pressing questions: how do residents interact with their space and how do they perceive ruination? What type of local narratives do they produce?

While much research has focused on the “ghost city” (guicheng 鬼城) phenomenon in coal regions – new districts characterised by a large number of vacant brand new buildings and infrastructures, produced by anticipatory urbanism and real estate speculation as in Ordos (Shepard 2015; Sorace and Hurst 2016; Ulfstjerne 2017; Woodworth and Wallace 2017; Yin, Qian, and Zhu 2017) – ruination in Kouquan corresponds more to the image of the “ghost town”: a former mining boomtown urbanised during the early period of the industry that became less relevant at a later stage. Such abandoned mining towns exist in other contexts, including the United States (DeLyser 1999), Zimbabwe (Kamete 2012), and Russia (Andreassen, Bjerck, and Olsen 2010): “Not only do things become more present, more manifest, but in some ways they also become more pestering and disquieting” (ibid.: 23). In China, for example, in “instant cities” that developed during the Cold War in Sichuan Province (Lam 2020), the population is completely gone and the visitor is left alone with abandoned buildings and infrastructure.[10] In this case, Kouquan is not a fully abandoned industrial space. Although the town seems empty, it is connected to the city via the public bus service. It is also still inhabited, although it has lost most of its population and the mark of the work unit is gone.

There are no Chinese expressions equivalent to the “ghost town” image, but terms such as “abandoned” (huangfei 荒廢), “uninhabited” (wuren 無人), or “hollow” (xinkong 心空) often qualify villages and towns that have not been redeveloped for tourism, as well as their “left-behind” (liushou 留守) population. Abandoned buildings in decay constitute the background in Kouquan. Yet, beyond the lenses of postsocialist and postindustrial disconnection, Kouquan remains invested by actors who reinvent local practices and meanings in and with the ruins. These social perceptions and appropriations of the local space reveal reconnecting spatialities – that is to say, socio-spatial experiences of the built environment. In order to better grasp how ruination can produce a sense of place in this “uninhabited” industrial space (following Boudot, Delouvrier, and Siou 2019; Raga 2019), I study how local practices and narratives produce a specific sense of place. This article shows that in Kouquan, different spatialities – of dwelling, religious practices, art forms, memory, and heritagisation efforts – constitute reconnecting experiences that maintain and recreate a sense of place. Because these spatialities result from interactions with the buildings in decay, ruination constitutes an important connector. The rubble acts “not as self-contained relics of a specific time and space or as mere stones, rocks and walls devoid of meaning, but as marks of the landscape that make it possible to draw connections between their past and present” (Raga 2019: 19). Ruination is thus a process happening in uninhabited industrial spaces, allowing them to keep a strong local identity. The notion of uninhabitedness carries a critique to the paradigm of “disconnection” (Vaccaro, Harper, and Murray 2016). Ruination in Kouquan develops as a different process than the fast and violent demolition processes – studied by Shao Qin (2013) under the concept of “domicide” – in Chinese cities, suggesting that other dynamics of ruination exist in less urban, less central, and less dense spaces. Indeed, such uninhabited industrial spaces experience slow decay where the built environment does not attract real estate actors. As one resident told me, “This place has not been developed by the government” (zhengfu meiyou kaifa ne 政府沒有開發呢) (informal discussion with a few residents, 22 June 2019). City officials also stated in 2018 that there was no plan to redevelop Kouquan (interview with Datong City officials, September 2018). It reveals a lack of attention that results in the slow ageing of the town, preserving it partly from demolition and keeping available the opportunity for future heritagisation. As Tim Edensor explains, “A far more multiple, nebulous and imaginative sense of memory persists in everyday, undervalued, mundane spaces which are not coded in such a way as to espouse stable meanings and encourage regular social practices” (2005: 139). The mining industry in Shanxi has produced what Alice Mah calls “place-based communities” (2012: 4), deeply rooted in the local territory: “Despite their state of disuse, abandoned industrial sites remain connected with the urban fabric that surrounds them: with communities; with collective memory; and with people’s health, livelihoods, and stories” (ibid.: 3). Kouquan Town has lost most of its inhabitants, but the buildings in ruins maintain various interactions with the population, both local and non-local. Studying the connection between ruination and sense of place in Kouquan thus provides insight into how left-behind residents relate to their own urban spaces in decay, and how multiple on-site and off-site actors interact with the ruins.

Urban exploration as method for the ethnography of China’s abandoned places

This article on ruination in Kouquan Town is part of a larger ethnographic research on Datong’s urban development and spatial restructuring after the coal boom. I lived in Datong for 15 months corresponding to six field trips from 2015 to 2019. From April 2016 until June 2019, I went to Kouquan Town and its surroundings on a weekly basis. Understanding how ruination in Kouquan imbues the practices and narratives of local actors sheds light on Datong’s social and spatial configurations in the post-coal era. While being confronted with several challenges,[11] the main one was the difficulty in conducting in-depth interviews due to the lack of population in the old town. I chatted with 15 residents and workers (in a residents’ committee and at the train station) encountered during my visits. These residents had grown up in Kouquan and were farmers, unemployed, or retired, the youngest being over 40 years old. I had informal discussions with them, sometimes turning into longer, more in-depth discussions. I could not record the discussions because they mostly took place in the street and because it made them uncomfortable. Yet, I was able to memorise and write down some of their quotes in my journal immediately after walking away and sitting down around the corner.

Many of the residents did not remember precisely the stages of ruination: “It has been abandoned for several decades (ji shi nian 几十年), I don’t remember exactly,” were common comments. They also did not know or did not remember the functions of unidentified abandoned buildings. They did not have old street photos, and they had few physical archives or objects in their small houses. Precise information, such as quantitative data on this ageing mining town, was not available.

My investigation was also based on direct observation during 13 on-site visits, each time during at least half a day, trying to grasp the relationships between the residents and the abandoned buildings. Considering the strong proportion of abandoned houses and buildings, I used urban exploration (urbex), an activity that consists in visiting and documenting abandoned sites and buildings. I studied the material “traces,” “clues,” and “signs” (Ginzburg 1980) of Kouquan’s abandoned buildings and their effects on the people that lived near them, as well as on more distant actors. I drew maps and took notes directly in the streets. Because human occupation only partly fills the space, Kouquan’s identity is also architectural, embodied in the town’s layout and its buildings in decay. Writing descriptions in my journal and photographing both the buildings and how people invested them with activities and representations provided a more complete image of the place.[12] Exploring abandoned buildings allowed me to analyse the structure and texture of ruination, not only from outside, but also from inside and from the emic perspective of their social worlds. Many elements were observed during field visits, written down in my journals, and analysed at a later stage.

In parallel, I carried out fieldwork in other mining villages around Datong, as well as in a relocation neighbourhood for coal miners. This larger perspective on coal mining villages and towns gave me more insights into the ethos of miners, their history, and their everyday lives. For this research, I also did a review of official government regulations (from the provincial level to the local level) since the early 2000s, news reports, and online publications by ordinary citizens (blog posts, etc.), additionally using other cultural materials (films).

Map. Kouquan area

The first section of this article documents the materiality of Kouquan Old Street’s ruins, based on urban itineraries and fieldnotes collected between 2016 and 2019, bringing out the spatialities of such uninhabited spaces. In a second section, I study the last residents’ living conditions and interactions with the abandoned buildings. Finally, the article discusses the various narratives, which, while disunited, contribute to producing a sense of place and memory in Kouquan.

The texture of ruination: Dust and silence in Kouquan

Kouquan Old Town is located at the crossroads between Datong’s minefields and Datong urban area. Bus line No. 1 operates as one of the oldest bus lines reaching Kouquan from the city centre. Just before arriving to Kouquan, the landscape becomes less urbanised and finally turns into a succession of derelict buildings on both sides of the road: abandoned restaurants and hotels, half-demolished houses. Through the town, most buildings and houses are disused and uninhabited. The upper road to the mines displays architectural elements from different periods. At the entrance of the town, there is an abandoned building dating from the Republican era (observation in Kouquan, May 2016). Some buildings carry historical traces from the Mao era, such as political slogans engraved on the facades: “United, intense, serious, active” (tuanjie, jinzhang, yansu, huopo 團結, 緊張, 嚴肅, 活潑) can be read on the walls of a former grain station. However, there is no visible presence of the mining company’s signs on the building’s walls.

The old town has slowly lost its commercial and service functions and it continues to lose both its residents and amenities. As an illustration, the train station for passengers closed in 2012. This train station was formerly of major importance. When the mining economy was booming, the railway line was in constant use, as Mr. Zhang explains:

There used to be so much passenger traffic, over 100 years, along with the development of the coal mines. The train for passengers cost only 1 yuan to go to Datong train station, and coal miners did not need to pay. (…) Many coal trains used to pass here too. Now, today, we count only 400 or 500 coal trains, but before, the daily traffic was 1,200! As for passengers, there used to be around 1,000 people per day. (Discussion with Mr. Zhang, director of the train station, 25 June 2016)

Today, the train station has been converted into a badminton sport field, and the building now serves as a community space for the railway staff. My discussions with local residents indicate that the town started declining in the 1990s, when new infrastructure and services emerged closer to Datong’s city centre. The area carries visible scars of mining on the local landscape and other industrial wastelands: an abandoned cement factory, small derelict factories overgrown by nature, food cooperatives from the Mao era. Near the train station, the streets are covered in a thick layer of coal dust. Up in the hills, collapsed buildings carry signs with the warning “Dangerous house” (weifang 危房). These signs indicate that part of the local architecture is now “unsafe,” due to land-subsidence: “This place is subject to land-subsidence, pedestrians keep safe” (cichu you dixian, xingren zhuyi anquan 此處有地陷, 行人注意安全) can be seen on several buildings in the main street. The issue of mining-induced land-subsidence (Zhang 2013; Yang, Zhao, and Ho 2017) is part of the reason why the town is uninhabited. A major urban renewal operation was launched in 2007 to relocate the residents living in shanty towns into residential compounds (xiaoqu 小區), but a proportion of residents has not been able to move out yet. While the work unit took care of the coal miners, Kouquan’s non-mining population was not included in the relocation policy at first.[13] Some people also did not have the financial means to move out, hence the presence of retired families in Kouquan.

The traces of the planned economy are visible. The layout of the industrial town follows a standardised plan. The main street has a diversity of shops and services: a restaurant (Figure 1), a cinema (Figure 2), convenience stores (Figure 3), a public bath, a clinic, a barber’s shop (Figure 4), the former town government, a large Xinhua bookshop, and a Christian church. These abandoned shops stand right next to one another, confirming Kouquan’s former commercial density. All the shops have been closed for decades, except for the barber’s shop. This alignment of abandoned shops reinforces the impression of decay and desertion. Because they have been left untouched since being closed down, these abandoned storefronts participate in the image of a ghost town. The uninhabited nature of the space is confirmed by the absence of any logo of the mining company. The facades carry the name Kouquan, engraved in stone, maintaining a spatial identity.

The diversity of functions of the shops and their rather large surfaces suggest that this place was “developed and prosperous” (fada yu fanhua 發達與繁華). Kouquan is characterised by small lanes with abandoned self-built houses in various architectural styles, from the typical Shanxi-based yaodong (窯洞) dwellings – cave dwellings – to simpler village houses (pingfang 平房) and yards as well as Buddhist temples.

Figure 1. The abandoned restaurant, Kouquan, May 2016. Credit: author.

Figure 1. The abandoned restaurant, Kouquan, May 2016. Credit: author.

The architecture of abandoned buildings contains evidence of the former organisation of Datong’s mining communities. While the industrial era stimulated Kouquan’s urban development, the process of abandonment redefines its urban-rural nature. The town is still connected to the city by public buses, but rural activities are now more visible than industrial ones. As an example, Figure 1 shows that the former restaurant on the main square is now used for stocking corn plants. As for Kouquan’s former Workers’ Cultural Palace (Gongren wenhuagong 工人文化宫) built in 1952 by the Mining Bureau[14] that served as a cinema, it is now used as a wood-cutting workshop (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Workers’ Cultural Palace, Kouquan, June 2016. The Chinese characters “文化宫” (wenhua gong, cultural palace) have faded away but still appear on the left side of the building. Credit: author.

Figure 2. The Workers’ Cultural Palace, Kouquan, June 2016. The Chinese characters “文化宫” (wenhua gong, cultural palace) have faded away but still appear on the left side of the building. Credit: author.

Dwelling amongst ruins and ghosts

Ruination in Kouquan Town is an important element of the uninhabited industrial space. I now explore the interactions between the residents and these abandoned buildings. In old Kouquan, there is still a residents’ committee in charge of the population, two small barber’s shops, one tomb maker and one shop for alcohol and tobacco (yanjiu 煙酒). The employees told me that the population was shrinking because younger generations moved to other places in Datong or to other cities. Additionally, the last residents are not only retired miners but also farmers (nongmin 農民) who rely on minimum welfare (dibao 低保), far from the social benefits provided to coal miners: “The last residents have very heavy social difficulties. They have no retirement pension, unlike Tongmei miners. Most of them are dibao recipients” (discussion with three residents’ committee employees, 25 June 2016).

Just as the buildings have been ageing in place, Kouquan’s last residents have aged with the town since the early Mao era. Their housing conditions are simple: small single-storey houses or “pingfang,” and village houses with a yard. In the street, people’s routines consist in resting, chatting with neighbours or playing cards, growing vegetables, sitting outside while sewing or knitting, getting a haircut: “We don’t have hobbies, we have very simple activities here” (informal discussion with residents playing cards, 22 June 2019). A combination of two types of feelings emerges: feelings of attachment and rootedness, but also feelings of isolation and exile, as people feel left-behind in poverty, not being able to access better living conditions. While many interviewees were aware of the large-scale relocation policy implemented in Datong’s coal mining settlements, they said they were not included in the programme: they “did not have any money” to move (meiqian 沒錢), they “did not belong to the category of coal miners” (bu shi kuanggong 不是礦工), and “nobody cared” (mei ren guan 沒人管). The people who still live here have not been able to move because they are not Tongmei workers, and because they are stuck between the administrations of two districts – Nanjiao District and the Mining District: “None [of these two administrations] cares” (shei dou bu guan 誰都不管) (informal discussion with a resident, 2 May 2018).

Most of their descriptions of Kouquan started with the uninhabited landscape, not so much in a material but in a social dimension: “Most people moved out many years ago;” “People are gone.” A second statement points out to the lack of services: “All the shops are now closed;” “There is nothing here anymore” (zheli shenme dou meiyou le 這裡什麼都沒有了). The sense of being poor but also becoming “minor,” the sense of a reduced community, and the sense of loss were emphasised. These descriptions dominated the description of the landscape: instead of talking about the materiality of ruins, either as “historical sites” (yizhi 遺址), “rubble” (feixu 廢墟), or “buildings” (fang 房), they spoke of the people who had left, the lost “liveliness” (renao 熱鬧) and the current emptiness of the spaces devoid of people. The sense of uninhabitedness was stronger than the sense of decay. Many interviewees considered it important to describe the present by reminding the visitor of how the town was in the past: “There was Kouquan before there was Datong!” was a recurrent statement. Their local narratives emphasise the past “flourishing” times of Kouquan: “The gravity centre of this area was here and not in Datong” (informal discussion with a local resident, 30 April 2017). According to the hairdresser, the town used to have a population of 30,000 residents at its peak of prosperity.[15] In the 1990s, “Kouquan was the commercial epicentre of the area, from Huairen to here. (…) There was everything, from restaurants to hotels and shops; there was even an ice-lolly factory, next to the water fountain!” says the hairdresser.[16] The residents’ historical narratives about Kouquan “being there before Datong” contrast with the narrative on Datong’s ancient history promoted by the city government.

Many of Kouquan’s last residents feel “left-behind” (also noted in other contexts, e.g. Mah 2012: 7) witnessing the town fall into decay, in the context of a larger restructuring of the coal industry in Datong that created a lot of uncertainty and worry for families (Audin 2020). They also feel left-behind by the urban renewal programme: the relocation programme aiming to solve the problem of land-subsidence due to decades of aggressive industrial mining has not been fully implemented in Kouquan.

Figure 3. A group of elderly male residents sit on the threshold of a closed convenience store, Kouquan, May 2017. Credit: author.

Figure 3. A group of elderly male residents sit on the threshold of a closed convenience store, Kouquan, May 2017. Credit: author.

Figure 4. A group of elderly female residents spend time in front of the barber’s shop, Kouquan, May 2018. Credit: author.

Figure 4. A group of elderly female residents spend time in front of the barber’s shop, Kouquan, May 2018. Credit: author.

While the last residents are marginalised from urban lifestyles, ruination in Kouquan contributes to reinventing their local spatial practices, especially dwelling. Abandoned buildings offer a familiar space for the long-term community, with close-knit networks of people spending time chatting with one another. There is a close proximity between the residents and the abandoned buildings. Because their self-built houses are small, there is not much space available for gathering inside. Residents thus spend time sitting by the closed shop entrances (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Although there is a gendered division of space, typical of coal mining neighbourhoods, both groups of male residents and female residents use the abandoned buildings as their daytime meeting spots. Far from being avoided, the abandoned buildings provide new spaces for their daily discussions and games, hence the appropriation of porches with chairs, sofas, and stools.

In general, although many residents are eager to leave for better living conditions and hope that relocation will represent an opportunity to escape poverty, they are used and attached to their houses in the town. One resident, Ms. Zhu, a middle-aged woman living with her son in a small room in a narrow alleyway, told me that even if the relocation policy was implemented in her street, she would not want to leave her house:

The houses here are more than 100 years old! Can you imagine how strong they are, they are very strong of course! They say the ground is unsafe but I don’t believe that my house will collapse. I want to stay here. (Discussion with Ms. Zhu, 30 April 2017)

Ms. Zhu also told me she lived off the public welfare system and her time was dedicated to taking care of her disabled son. She had gotten used to her routine in the village and did not easily project herself moving out of her Kouquan home.

According to Mr. Li, another middle-aged resident living in a courtyard house from the Ming-Qing era, everybody else in the yard left “many years ago,” and some of them even left everything in place. He was proud to show me the different corners of the house, talking about the valuable quality of traditional architecture, a courtyard house with yaodong components. He told me that several families used to share the courtyard. Each one used to live in different rooms. Interestingly, he told me I could visit this house: “But not too often, because the house has a ‘ghost’ (gui 鬼) and (…) you could get in trouble” (informal discussion with Mr. Li, 25 May 2016). While he warned me about the ghost in the house, the man did not appear to be bothered by the ghost himself and continued to enjoy living alone in the house. He simply did not touch the other residents’ former rooms. By emphasising the difference between insiders and outsiders in relationship to ghosts, Mr. Li described an intimate relationship with his home (jia 家) and the double identity of this historical house: between a haunted house and a home.

Finally, the connection to Kouquan is perpetuated by former locals who maintain their visits even after having moved out. Family members visit their relatives or keep a house in Kouquan even after moving away, maintaining social networks that gravitate around Kouquan. Mr. Xi, for instance, worked in a coal washing unit at the time of the interview (informal discussion with Mr. Xi, 2 May 2018). His wife was a housewife. He had lived in Kouquan for 40 years before moving out. He earned a monthly salary of 3,000 RMB “because the coal value has dropped below its original value.” With his family, he moved to Tongmei’s relocation neighbourhood a few years ago. He still owned a house in Kouquan, so he was going back every week on his day off work. He still had friends in Kouquan and he continued to grow vegetables there.

Such relationships to the buildings by locals and former inhabitants suggest a form of connection through “‘living memory,’ (…) defined as people’s memories of a shared industrial past, as opposed to ‘official memory’ or ‘collective memory’” (Mah 2010: 402). Moreover, although most residents miss the former social life and density, ruination opens spaces that allow the remaining residents to dwell in place and to enjoy calmness in the current site.

A sense of place without a shared narrative

Beyond the reinvention of dwelling in Kouquan, ruination also creates a sense of place through the interactions and narratives produced by various actors, from journalists and cadres of the government to ordinary people. The narrative of decline seems dominant in scope and in scale, spread both through visual reports by news agencies and by administrators. News reports in English and in Chinese warn that the mining land in Shanxi has become dangerous and many villages are sinking.[17] At the same time, the cultural narratives studied below enrich and complexify the representations of uninhabited Kouquan, as they emerge from the experience of ruination and contribute to reshaping a sense of place.

The abandoned landscape in Kouquan reveals a strong connection between space and memory. The way the last residents value the long history of this area creates a sense of place that does not relate to the main space of production, but that characterises this uninhabited industrial area. A form of living memory is also enacted in the many online reports posted by former residents about their hometown. Indeed, individuals and groups contribute to narrating its memory from their own experiences. Although they did not have photographs of ordinary life in the village – people mostly owned marriage photos and family pictures – they had “deep” memories of growing up and living in Kouquan. Several blog posts found online express the nostalgic recollections of former residents returning to old Kouquan for a walk, now posting photos of their urban explorations in the ruins and commenting on their feelings towards the abandoned buildings. For instance, under the photo of an abandoned convenience shop, one blog post reads, “This used to be a shop full of shelves filled with goods and things that were a feast to the eyes (linlangmanmu 琳琅滿目).”[18] Such nostalgic discourses recount other forms of consumption and dwelling, when people had “no money” yet would still go out to the shops as a leisurely practice. Other visitors, mostly coming from Datong City, also explore and comment on Kouquan’s ruined buildings: in one video, one person comments that the public toilets are in better condition than the houses in the lane.[19]

As representatives of the town’s past, among other residents, the 70-year-old hairdresser and his wife are eager to tell Kouquan’s history and to narrate the town’s trajectory. They are indeed proud of their old objects and furniture. The barber showed me the chair “from the late Qing Dynasty” and other hairstyling tools from the early Mao era. Their efforts to keep their shop open is a living proof of place appropriation and local commitment to the remaining residents, by offering a cheap service and maintaining both their appearance and social ties.

Kouquan is also a source of inspiration for Datong-based painter Yu Xiaoqing 于小青, who grew up there. [20] According to him, people who were born there had a deep connection to the place: “Each shop, each person (…) we particularly remember this [place] (jiyi youshen 記憶尤深).”[21] In 2017, because he was afraid the old town would be demolished and no trace would remain, he decided to paint abandoned buildings and street scenes: “Some people use photography to document the place. I use painting as a way to record the memories.”[22] On his webpage, a few comments by former Kouquan residents express gratitude for his memorialising effort.

Beyond the individualised narratives of nostalgia, there are groups of local residents of Datong and Kouquan that unite to push for the heritagisation of Kouquan. In April 2018, a public comment was addressed to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.[23] The text mentions that the Kouquan area displays precious architectural features from several historical periods:

In the east-west street, there are buildings, shops, cinemas, restaurants, hair salons dating from the planned economy of the 1950s – 1960s, as well as architectural features of the Cultural Revolution era, with residential houses displaying various architectural models such as courtyard houses of the Ming and Qing Dynasty, terraced houses, yaodong etc. (…) Kouquan Old Town kept exemplary architectural features from the early PRC, the Cultural Revolution, and the reform era, with a train station, a theatre stage, a governmental office, a theatre, residential houses, and other popular historical remains with a rather high preserved value, worthy of filming movies, or for photography.

It also mentions the vulnerability of the last residents:

Following the exhaustion of the exploitation of Kouquan area through coal mining, the old days of prosperity (xiri de fanhua 昔日的繁華) are now far away (…). The ones who stayed in the old town are mostly elderly people. A lot of them experienced the War of Resistance against Japan and the Civil War. A lot of them are also coal miners from that period. Although the former popularity of the place has slowly declined, the old architecture reminds anyone of the old town’s former brilliant history.

Local residents and external actors hope that the government will value the town’s diverse historical architecture and memory. However, the response of the Mining District government expresses another narrative. It states that the Mining District does not have authority in matters of planning or building refurbishment, nor in heritage preservation. The Mining District government acknowledges the principle of industrial heritage protection while justifying the narrative of modernisation through demolition, as it is the case in most Chinese cities: demolition aims to “improve the residents’ living conditions” (gaishan minsheng wenti 改善民生問題).

Journalists also produce a narrative on Kouquan’s “cultural” value.[24] In one report, a journalist explains that “Kouquan Old Street is like an old man, lonely (gudu 孤獨) and sad (guku 孤苦).” He wishes that this place could become a “cultural street” (wenhuajie 文化街).[25] Moreover, as mentioned in the introduction, Shanxi-based filmmakers use Kouquan as a movie set. Its abandoned streets inspire cinematic narratives.

Not only is the living memory of the town and its history still strong, the area is also valued for its religious character with the strong presence of temples. Each time I walked across the village, residents always assumed that I was looking for the “Temple of the Thousand Buddhas” (Qianfosi 千佛寺), one of the Buddhist temples located on the hills, and started pointing me in the direction of religious sites. Local rituals are still practiced by Datong residents and by the remaining residents in Kouquan. Next to the Workers’ Cultural Palace, one Buddhist temple seems active from outside, but when I visited it, the couple who guarded it told me not much happened on an everyday basis. The temple pavilions were in poor condition, and traces of cement on the ground suggested a failed attempt to restore them: “There was an effort to renovate the temple eight years ago, but in fact, there was no money to restore it. It stayed half-finished, like you see now” (discussion with Ms. Ning who guards the temple, 2 May 2018). Yet, the couple was proud of the one important event of celebration of the 8th day of the 4th month of the lunar calendar. During the traditional festival of Siyueba (四月八), the local temple holds a fair that attracts a crowd of locals.[26]

The entanglement of these various narratives draws together in a collective sense of place, following the emergence of a clearer line of governance by the new district in charge – Yungang District. In April 2020, the Datong City Yungang District government announced that an association to study the history and culture of Kouquan had been founded.[27] This case thus calls for more research on the future development of the town memory.

Conclusion

This article examined the ruination process and its material and social effects in uninhabited industrial spaces. Ruination develops specific spatialities – of dwelling, memory, religious and cultural practices – that maintain and recreate a sense of place. The public authorities have introduced new norms of governance for the coal mining land, and former mining settlements, considered “dangerous” due to land-subsidence and lack of maintenance, have been depopulating since the mid-2000s. Yet, ruination in Kouquan perpetuates and renews the social and spatial practices of left-behind residents as well as the representations of non-locals who continue to visit Kouquan. From a coal hub to a town neighbourhood on the urban fringe, ruination in Kouquan reveals various active interactions between people and their built environment. This case expands the study of uninhabited spaces, the destiny of which is often viewed through a frame of disconnection. Ruination in Kouquan is a process that suggests reconnecting spatialities, not only in the way remaining residents integrate the ruined buildings into their dwelling experiences, but via the varied narratives associated with place: from intimate representations to political, journalistic, cultural, religious, and cinematic narratives, Kouquan reconnects with other publics. Uninhabited spaces – industrial spaces in this case, but also left-behind villages and towns – therefore constitute important objects for the study of Chinese society. In a rapidly urbanising China, ruination in such uninhabited spaces shows how new meanings and identities are shaped by the material texture of decay and dust in the street.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on research funded by the MEDIUM project and by the CEFC. I would like to thank Katiana Le Mentec, Camille Salgues, Sean Philips Smith, as well as the anonymous reviewers and the editorial team of the journal for their valuable comments on former versions of this article. All shortcomings are my own.

Judith Audin is a political scientist specialising in urban studies. She is a former researcher at CEFC and Chief Editor of China Perspectives, and is now an associate researcher at CECMC, EHESS. CECMC, Campus Condorcet, Bâtiment EHESS, 2 cours des Humanités, 93300 Aubervilliers, France (audin.judith@gmail.com).

Manuscript received on 16 March 2021. Accepted on 9 November 2021.

References

ANDREASSEN, Elin, Hein Bjartmann BJERCK, and Bjørnar OLSEN. 2010. Persistent Memories: Pyramiden, a Soviet Mining Town in the High Arctic. Trondheim: Tapir Academic Press.

AUDIN, Judith. 2020. “The Coal Transition in Datong: An Ethnographic Perspective.” Made in China Journal 5(1): 34-43.

BOUDOT, Anaïs, Marine DELOUVRIER, and Hervé SIOU. 2019. “Approcher l’Espagne déshabitée : retours d’expérience. Photographier, dessiner et écrire sur un habiter particulier” (Feedback on Approaching Uninhabited Spain: Photographing, Drawing, and Writing on a Specific Dwelling Form). À l’épreuve, revue de sciences humaines et sociales, 18 February 2019. http://alepreuve.org/content/approcher-lespagne-déshabitée-retours-dexpérience-photographier-dessiner-et-écrire-sur-un (accessed on 22 June 2020).

CHO, Mun Young. 2013. The Specter of “the People”: Urban Poverty in Northeast China. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

CUI, Jinze. 2018. “Heritage Visions of Mayor Geng Yanbo: Re-creating the City of Datong.” In Christina MAAGS, and Marina SVENSSON (eds.), Chinese Heritage in the Making. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. 223-44.

CURRIER, Jennifer. 2008. “Art and Power in the New China: An Exploration of Beijing’s 798 District and its Implications for Contemporary Urbanism.” Town Planning Review 79(2/3): 237-65.

DELYSER, Dydia. 1999. “Authenticity on the Ground: Engaging the Past in a California Ghost Town.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 89(4): 602-32.

EDENSOR, Tim. 2005. Industrial Ruins: Spaces, Aesthetics and Materiality. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

FU, Shulan, and Jean HILLIER. 2018. “Disneyfication or Self-referentiality: Recent Conservation Efforts and Modern Planning History in Datong.” In Yannan DING, Maurizio MARINELLI, and Xiaohong ZHANG (eds.), China: A Historical Geography of the Urban. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 165-92.

GILLETTE, Maris Boyd. 2016. China’s Porcelain Capital: The Rise, Fall and Reinvention of Ceramics in Jingdezhen. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

——. 2017. “China’s Industrial Heritage without History.” Made in China Journal 2(2): 22-5.

GINZBURG, Carlo. 1980. “Signes, traces, pistes. Racines d’un paradigme de l’indice” (Signs, Traces, Leads. Roots of a Clue Paradigm). Le Débat 6(6): 3-44.

HO, Cheuk Yuet. 2013. “Bargaining Demolition in China: A Practice of Distrust.” Critique of Anthropology 33(4): 412-28.

KAMETE, Amin Y. 2012. “Of Prosperity, Ghost Towns and Havens: Mining and Urbanisation in Zimbabwe.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 30(4): 589-609.

LAM, Tong. 2020. “Urbanism of Fear: A Tale of Two Chinese Cold War Cities.” In Richard BROOK, Martin DODGE, and Jonathan HOGG (eds.), Cold War Cities: Politics, Culture, and Atomic Urbanism. London: Routledge. 115-21.

LEAN, Eugenia. 2020. Vernacular Industrialism in China: Local Innovation and Translated Technologies in the Making of a Cosmetics Empire, 1900-1940. New York: Columbia University Press.

LI, Jie. 2020. Utopian Ruins: A Memorial Museum of the Mao Era. Durham: Duke University Press.

LONG, Ying, and Shuqi GAO (eds.). 2019. Shrinking Cities in China: The Other Facet of Urbanization. Cham: Springer.

MAH, Alice. 2010. “Memory, Uncertainty and Industrial Ruination: Walker Riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 34(2): 398-413.

——. 2012. Industrial Ruination, Community, and Place: Landscapes and Legacies of Urban Decline. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

ORTELLS-NICOLLAU, Xavier. 2015. Urban Demolition and the Aesthetics of Recent Ruins in Experimental Photography from China. PhD Dissertation. Barcelona: Autonomous University of Barcelona.

RAGA, Ferran Pons. 2019. “As it Was, as it Is: Tourism Heritage Strategies in the Abandoned Village of Peguera (Catalan Pyrenees).” Catalonian Journal of Ethnology 44: 16-31.

REN, Xuefei. 2014. “The Political Economy of Urban Ruins: Redeveloping Shanghai.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38(3): 1081-91.

REN, Xuefei, and Meng SUN. 2012. “Artistic Urbanization: Creative Industries and Creative Control in Beijing.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36(3): 504-21.

SHAO, Qin. 2013. Shanghai Gone: Domicide and Defiance in a Chinese Megacity. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

SHEPARD, Wade. 2015. Ghost Cities of China: The Story of Cities without People in the World’s Most Populated Country. London: Zed Books.

SORACE, Christian, and William HURST. 2016. “China’s Phantom Urbanization and the Pathology of Ghost Cities.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46(2): 304‑22.

ULFSTJERNE, Michael A. 2017. “The Tower and the Tower: Excess and Vacancy in China’s Ghost Cities.” In Susanne BREGNBÆK, and Mikkel BUNKENBORG (eds.), Emptiness and Fullness: Ethnographies of Lack and Desire in Contemporary China. New York: Berghahn Books. 67-84.

VACCARO, Ismael, Krista HARPER, and Seth MURRAY (eds.). 2016. The Anthropology of Postindustrialism: Ethnographies of Disconnection. London: Routledge.

WOODWORTH, Max D., and Jeremy L. WALLACE. 2017. “Seeing Ghosts: Parsing China's ‘Ghost City’ Controversy.” Urban Geography 38(8): 1270-81.

WU, Hung. 2012. A Story of Ruins. Presence and Absence in Chinese Art and Visual Culture. London: Reaktion Books.

YANG, Xiuyun, Heng ZHAO, and Peter HO. 2017. “Mining-induced Displacement and Resettlement in China: A Study Covering 27 Villages in 6 Provinces.” Resources Policy 53: 408-18.

YIN, Duo, Junxi QIAN, and Hong ZHU. 2017. “Living in the ‘Ghost City’: Media Discourses and the Negotiation of Home in Ordos, Inner Mongolia, China.” Sustainability 9(11): 2029-43.

YU, Jing, Zhongjun ZHANG, and Yifan ZHOU. 2008. “The Sustainability of China’s Major Mining Cities.” Resources Policy 33(1): 12-22.

YUNG, Esther Hiu Kwan, Edwin Hon Wan CHAN, and Ying XU. 2014. “Sustainable Development and the Rehabilitation of a Historic Urban District – Social Sustainability in the Case of Tianzifang in Shanghai.” Sustainable Development 22(2): 95-112.

ZHANG, Yulin 張玉林. 2013. “災害的再生產與治理危機 – 中國經驗的山西樣本” (Zaihai de zai shengchan yu zhili weiji – Zhongguo jingyan de Shanxi yangben, Disaster Reproduction and the Crisis of Governance: The Shanxi Sample in China’s Experience). Rural China: An International Journal of History and Social Science 10: 83-100.

[1] “同煤二礦拍攝的大片獲得大獎” (Tongmei erkuang paishe de dapian huode dajiang, The Film Shot in Tongmei’s Mine No. 2 Received an Important Award), Tongmei renjia (同煤人家), 13 August 2018, https://m.sohu.com/a/231483937_226871 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

[2] “尋訪老口泉” (Xunfang lao Kouquan, Searching for Old Kouquan), Datong ribao (大同日報), 19 January 2021, http://www.dt.gov.cn/dtzww/mldt/202101/d0b731659e0b4ad5836bc15bd09a3daa.shtml (accessed on 8 September 2021).

[3] “這裡是真實的世界嗎?跟著電影游大同老礦區和口泉老街” (Zheli shi zhenshi de shijie ma? Genzhe dianying you Datong lao Kuangqu he Kouquan laojie, Is This the Real World? Following the Film and Visiting Datong’s Old Mining District and Kouquan Old Street), Haokan shipin (好看視頻), 26 September 2020, https://haokan.baidu.com/v?pd=wisenatural&vid=7623364968303212052 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

[4] See scholar-artist Tong Lam’s website on Chinese ruins: http://visual.tonglam.com/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

[5] With the exception of Li Jie, “West of the Tracks: Salvaging the Rubble of Utopia,” Jump Cut, 2008, https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc50.2008/WestofTracks/index.html (accessed on 21 October 2020).

[6] See Zhou Hao’s documentary film The Chinese Mayor (2015) about Geng Yanbo’s urban transformation plan.

[7] On the government website, one of the first sentences about Datong reads, “The city is rated as ‘Top Tourist City of China’ and ‘the 9th ancient capital of China’.” See “A Brief Introduction to Datong,” Datong City People’s Government, 8 January 2021, http://www.dt.gov.cn/Home/zjdtywb/201701/fd3537a3aae14e81b90973ce8a8847a6.shtml (accessed on 15 November 2021).

[8] “山西大同區劃調整獲批: 撤銷城區, 南郊區, 礦區” (Shanxi Datong quhua tiaozheng huopi: chexiao Chengqu, Nanjiaoqu, Kuangqu, Datong’s District Redrawing Has Been Approved: Cancelling the Inner-city District, Nanjiao District, and the Mining District), The Paper (澎湃), 21 March 2018, https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forwaHrd_2035690 (accessed on 24 August 2020).

[9] 大同市地名志 (Datong shi diming zhi, Historical Records on Places in Datong City), Datong ribao sheyin shuachang yinshua (大同日報社印刷廠印刷), 1987.

[10] See also Xu Haifeng, “404: China’s Abandoned Nuclear City,” Sixth Tone, 19 October 2016, http://www.sixthtone.com/news/1451/404-china%20s-abandoned-nuclear-city (accessed on 28 August 2020).

[11] My research had several limitations. Being not fluent in the local Shanxi dialect, I could not grasp the full meaning of the people’s discourses, especially elderly residents. Moreover, I arrived in 2015 in the context of a political transition between the former mayor Geng Yanbo and the new city administration, so I could not meet government actors – even at the local level.

[12] I recorded my first visits in Kouquan in a blog post: “The Ruins of a Coal Mining Village,” China’s Forgotten Places and Urban Dystopias, 18 May 2016, http://ignition.eg2.fr/2016/05/18/the-ruins-of-a-coal-mining-village/ (accessed on 27 August 2020).

[13] See “山西採煤沉陷區: 到2020年65.5萬人將實現搬遷” (Shanxi caimei chenxianqu: dao 2020 nian 65.5 wan ren jiang shixian banqian, Land-subsidence in Shanxi: By 2020, 655,000 People Will Be Relocated), Shanxi ribao (山西日報), 3 June 2014, https://www.0352fang.com/datongloupan/xinwen/26353_1.html (accessed on 2 September 2020). The relocation process started in 2007 for Tongmei miners, but the relocation plan was only implemented in 2016 for other types of population: “關於印發‘大同市採煤沉陷區綜合治理地質環境治理專項工作方案(2016-2018年)’的通知” (Guanyu yinfa “Datong shi caimei chenxianqu zonghe zhili dizhi huanjing zhili zhuanxiang gongzuo fang’an (2016-2018 nian)” de tongzhi, Notice on the Implementation of “Special Work Measures of the General Governance of Datong City’s Zone of Land-subsidence and its Geological and Environmental Governance”), Datong City People’s Government 大同市人民政府, 2 November 2016, http://www.dt.gov.cn/dtzww/xmgk/201611/1da28d873276478fa58b874e5fc06307.shtml (accessed on 27 August 2020).

[14] “同煤故事: 口泉工人文化宫” (Tongmei gushi: Kouquan gongren wenhuagong, Tongmei Stories: Kouquan’s Workers’ Cultural Palace), Tencent Video (騰訊視頻), 11 March 2016, https://v.qq.com/x/page/b0187euonen.html (accessed on 28 August 2020).

[15] Interview available on https://www.ixigua.com/6715287078730465799?logTag=hXrUfHssKyYrI7f6PmJFN (accessed on 12 August 2020).

[16] Ibid.

[17] See “煤都大同採煤沉陷區之痛: 採空村房裂地荒水少” (Meidu Datong caimei chenxianqu zhi tong: caikongcun fanglie dihuang shuishao, Coal Capital Datong’s Land-subsidence Ache: In Sinking Villages the Houses Have Cracks, the Ground is Deserted and the Water is Scarce), Xinhuanet (新華網), 18 April 2016, http://finance.china.com.cn/industry/energy/mtdl/20160418/3681131.shtml (accessed on 2 September 2020); David Stanway, “Undermining China: Towns Sink after Mines Close,” Reuters, 17 August 2016, https://in.reuters.com/article/china-coal-environment/undermining-china-towns-sink-after-mines-close-idINKCN10S158 (accessed on 12 August 2020); Jason Lee, “China’s Sinking Coal Mining Towns and Villages in Pictures,” The Guardian, 9 September 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/gallery/2016/sep/09/chinas-sinking-coal-mine-towns-and-villages-in-pictures (accessed on 12 August 2020).

[18] “老家的回憶” (Laojia de huiyi, Memories of my Hometown), Jianshu (簡書), 11 March 2017, https://www.jianshu.com/p/c6fb751a9d01 (accessed on 8 September 2021).

[19] Datong Brother Tiger 大同虎哥, “大同市口泉老街看穆柯寨飯店多少年了? 穆桂英坡這麼好的一個小院沒人住?” (Datong shi Kouquan laojie kan Mukezhai fandian duoshao nian le? Mu Guiying po zheme hao de yi ge xiao yuan mei ren zhu? How Old is Mukezhai restaurant in Kouquan Old Street in Datong City? The Small Yard in Mu Guiying Lane is so Nice, How Come No One Lives in It?), Bilibili (嗶哩嗶哩), 10 August 2021, https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1c64y1s7on/?spm_id_from=333.788.recommend_more_video.14 (accessed on 8 September 2021).

[20] His paintings are displayed here: https://www.meipian.cn/1t1kaj9k (accessed on 8 September 2021).

[21] “于小青和他的‘口泉老街’” (Yu Xiaoqing he ta de “Kouquan laojie,” Yu Xiaoqing and his “Kouquan Old Street”), Renwu zhoukan (人物周刊), 1 February 2019, https://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XNDA0MzAyMTUwMA==.html (accessed on 8 September 2021).

[22] Ibid.

[23] “關於口泉老街保護和修復的建議的提案的答覆” (Guanyu Kouquan laojie baohu he xiufu de jianyi de ti’an de dafu, Response to the Suggestions on the Protection and Renovation of Kouquan Old Street), Datong City People’s Government 大同市人民政府, 4 April 2018, http://www.dt.gov.cn/dtzww/zxgb/201804/61691129564f421c8ca4f6c6c5a6fd9f.shtml (accessed on 21 August 2020).

[24] See for example Cui Liying 崔莉英, “追尋口泉老街的文化遺跡” (Zhuixun Kouquan laojie de wenhua yiji, Searching for Kouquan Old Street’s Cultural Relics), Datong wanbao (大同晚報), 9 February 2021, http://epaper.dtnews.cn/dtwb/html/2021-02/09/content_56_108205.htm (accessed on 8 September 2021).

[25] “大同口泉老街遊記‘追尋70年代的理髮館’” (Datong Kouquan laojie youji “zhuixun 70 niandai de lifaguan,” Visiting Datong Kouquan Old Street “in Search of the Barber’s Shop of the 1970s”), Wangyi shipin (網易視頻), April 2021, https://v.163.com/static/1/VS7PO38IC.html (accessed on 8 September 2021).

[26] See a report by Datong’s Association of Photographers: “老街舊巷, 再現繁華 – 口泉古鎮‘四月八’ 廟會 (Laojie jiuxiang, zaixian fanhua – Kouquan guzhen “Siyueba” miaohui, Old Street Old Lane, The Reappearance of Prosperity – The Temple Fair of “Siyueba” in Kouquan Old Town), News ZH (中文網), 23 May 2021, https://www.zhdate.com/news_travel/249028.html (accessed on 8 September 2021). Older photos are available here: http://www.360doc.com/content/17/1101/09/9444926_699926270.shtml (accessed on 21 May 2020).

[27] “雲岡區口泉歷史文化研究協會成立” (Yungangqu Kouquan lishi wenhua yanjiu xiehui chengli, Creation of the Yungang District Association to Study the History and Culture of Kouquan), Datong xinwen pindao (大同新聞頻道), 27 April 2020, https://www.sohu.com/a/391674927_100009062 (accessed on 6 September 2020).