BOOK REVIEWS

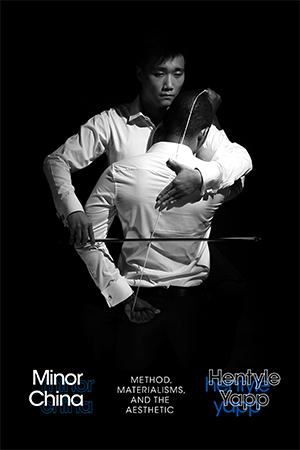

YAPP, Hentyle. 2021. Minor China: Method, Materialisms, and the Aesthetic. Durham: Duke University Press.

This book rethinks the relationship between the political and the aesthetic in contemporary Chinese art, against the dominant narratives that render non-Western art eligible through the logics of liberalism and capitalism. Indeed, the image of dissidents resisting an authoritarian state dominates the Western reception of contemporary Chinese art. It has been a major concern for art historians to discuss the depoliticised stories and multiple aesthetics in contemporary Chinese art (e.g. Wu and Wang 2010; Wang 2020). On the other hand, in area studies, how to make the non-West eligible without falling back to the Western-centric discourses is a persistent and crucial methodological question. Addressing alternative readings of contemporary Chinese art, this book assigns itself a crucial task central to both bodies of scholarship.

This book rethinks the relationship between the political and the aesthetic in contemporary Chinese art, against the dominant narratives that render non-Western art eligible through the logics of liberalism and capitalism. Indeed, the image of dissidents resisting an authoritarian state dominates the Western reception of contemporary Chinese art. It has been a major concern for art historians to discuss the depoliticised stories and multiple aesthetics in contemporary Chinese art (e.g. Wu and Wang 2010; Wang 2020). On the other hand, in area studies, how to make the non-West eligible without falling back to the Western-centric discourses is a persistent and crucial methodological question. Addressing alternative readings of contemporary Chinese art, this book assigns itself a crucial task central to both bodies of scholarship.

Although Minor China is not a straightforward title, the introduction immediately makes it clear what “minor” means in contrast to “major” and why it is crucial to think minor. The “major” approach is a materialist framework that reduces culture to its political and economic base, reproducing “liberal and recognisable understanding of the non-West” (p. 3). The minor as method is, by contrast, to hesitate from this dominant reading and attend to “the nuanced and vibrant intricacies” (p. 6) in art, such as “form, affect, nonvisual senses, nonanthropocentric objects, and speculation” (p. 10). As the theoretical backing of this method, the author refers to numerous theoretical traditions, including Marxism, new materialism, object-oriented ontology, Francophone metaphysical thought, Black feminist theory, and many others.

The book has five chapters, each with its own theoretical agenda. The first chapter aims to “produce a theory of the aesthetic for its relation to the political beyond a model of liberalism” (p. 34). The second chapter minors the liberal logics of inclusion through a leftist and Marxist understanding of inclusion. The third chapter engages with the debate on universality and particularity and questions why this debate recurs. The fourth chapter discusses subject and agency in Chinese performance art. While these four chapters attempt to achieve their goals through alternative readings of artwork by high-profile Chinese artists such as Cai Guoqiang 蔡國強, Ai Weiwei 艾未未, Zhang Huan 張洹, and Cao Fei 曹斐, the fifth chapter turns to the British artist Isaac Julien’s work Ten Thousand Waves. It is, however, a sound choice as the work was a response to the tragic death of Chinese migrants working as cockle pickers in the United Kingdom in 2004. Through the Black artist’s engagement with objectification of Chinese women, the author examines “the grand notions of totality and social structuration” (p. 35).

Despite its important task and ambitious programme, the book suffers from a few major problems that are likely rooted in the author’s preoccupation with theories and failure to synthesise the various theoretical strands he continuously draws in. The first consequence of such preoccupation is that theories often override the formal analysis of artwork, rendering the interpretation of artwork often far-fetched and detached from the work’s formal elements. For instance, in Chapter Four, the author thinks the figure of Mazu 媽祖 in Julien’s Ten Thousand Waves was the equivalent of what Benjamin saw as the angel of history in Paul Klee’s painting, but no formal resemblance between Paul Klee’s and Isaac Julien’s work is discussed. Throughout this chapter, the author claims that Julien “was informed by,” “reconfigures,” or “intermingles with” (p. 185-6) theoretical concerns central to this chapter, but these concerns are not evidenced by the artist’s own accounts or the formal elements of the artwork. The general impression is that the author’s agency has overridden the artist’s and the work’s. For this reason, the book may be less exciting for those whose primary interest is contemporary art.

Second, as the author constantly brings in new concepts, it is hard for the reader to see a coherent framework. Take Chapter Four as an example, which sets out to minor the understanding of Chinese artists as “herculean, conscious subjects resisting the authoritarian state” (p. 141). To rework the notion of “subject,” the author draws upon Rey Chow, and this guides the author to Jane Bennett’s critique of agency as demystification, which further prompts the introduction of Brecht’s theory of performativity and alienation effects (p. 148-51). As the author goes on, the snowball of concepts grows bigger. While I do admire the author’s strong theoretical literacy, I also wonder whether the reader would get easily disoriented. As stated at the beginning of this chapter, central to the author’s minor approach here are the concepts of “meditation” and “fabulation.” The former is an alternative term to “endurance,” which informs the dominant reading of Zhang Huan’s and He Chengyao’s 何成瑤 performance, and the latter can explain the detached performativity in Cao Fei’s work. A framework centring around these two concepts and their relation to subject and agency would probably have made this chapter more coherent.

Third, although the author envisages the book as a critique of liberalism and capitalism through rethinking Marxism, he is ambivalent about Marxism. In Chapter Two, he speaks of Chinese Marxism without giving it a clear definition. Is it Maoism, or the ideological apparatus that continues to serve the Chinese Communist Party, and how does it differ from Western Marxism? In Chapter Four, he asserts that Marxist revolution “forget[s] that to seize the means of production from the first world is premised upon the continual extraction of resources from the third” (p. 189). This assertion contradicts precisely the Marxist critique of colonialism and imperialism. Since the author often hesitates to define throughout the book, it is not always clear which “materialist concerns” are at stake and what “social structuration” means.

However, this book is also to be praised for other reasons. In Chapter Two, the author does present a close reading and stimulating discussion of Ai Weiwei’s Fairytale (Tonghua 童話), questioning the racialised condition of Chinese being plural. The author’s examination of women and queer artists is also a corrective to the dominant male perspective in art history. In addition to artistic practices, the author also brings in curatorial practices. The inclusion of Isaac Julien’s work in a book on contemporary Chinese art is unconventional but well justified and turns out essential for discussing China in relation to the West.

In general, this book could benefit from a more accessible writing style. The abundance of references and quotations interrupts the flow. In fact, when the author does not cite extensively, as in the afterword, he writes beautifully. It is also in the afterword that the author reveals his ambivalent and personal relationship to the “major.” He finds himself in an intellectual dilemma: “It is hard for me to pronounce a critique of China without it taking on an anti-Marxist bent that seemingly emerges from liberalism” (p. 211). This makes me question whether the author equates the Chinese state with Marxism and whether for him there is only one Marxist China. This is not to dismiss the author’s comment on the limited and often binary worldviews at our disposal, but to hesitate and pause – as advocated by the author – before we critique: is it not the binary thinking that prevents us from fully understanding the complexity of multiple China?

Linzhi Zhang is a British Academy postdoctoral fellow based at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Her research looks at the social production of contemporary art in China, situating the genesis of art in both the immediate exhibitionary and the broader societal context. The Courtauld Institute of Art, Vernon Square, Penton Rise, London, WC1X 9EW, United Kingdom (linzhi.zhang@courtauld.ac.uk).

References

WANG, Peggy. 2020. The Future History of Contemporary Chinese Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

WU, Hung, and Peggy WANG. 2010. Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents. New York: Museum of Modern Art.